COX’S BAZAR, Bangladesh — On a sweltering afternoon in a teeming settlement of more than half a million people, children draw, play games, and rattle tambourines in a lively community center built of bamboo. Vibrant artwork papers nearly every inch of the walls, and decorative constructions dangle from the rafters. Near the open doors, Amena Akter is sitting cross-legged, dabbing a brush into a fresh set of watercolor paints.

“This is me, and this is my mother, and the surrounding area is my village,” Amena, 10, tells me through a translator when I ask about her work. The scene is a happy one, with rolling hills and a rising sun in the background.

“It’s my homeland, in Myanmar,” she says.

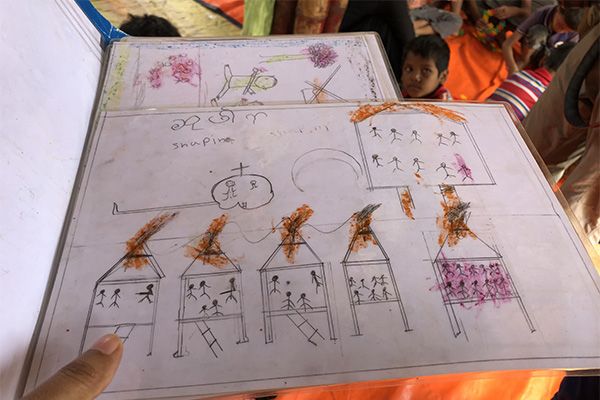

The depiction is far different from those made by children arriving as refugees in southern Bangladesh a year ago. When I visited, last month, an aid worker showed me a collection of drawings she keeps in a folder. Certain images reoccur: military helicopters, soldiers, homes on fire, and boats filled with stick-figure people. These are the children’s memories of violent attacks on their villages and of their escape from Myanmar to neighboring Bangladesh.

“When they first came to the CFS, they used to draw that type of picture,” the aid worker explains, using the acronym for Child-Friendly Space. This is a type of kids-only center erected in disaster and emergency situations by UNICEF and partners to support and protect children. “But now their pattern has changed. They are drawing flowers, houses, their family, their smiling faces.”

At this CFS in the Balukhali camp, part of a sprawling network of bamboo and plastic-tarp shelters on a barren hillside once covered by farmland and forest, aid workers use art and play to help uprooted children regain a sense of normality and overcome trauma. UNICEF and partners currently operate 136 of these centers in camps throughout the Cox’s Bazar district, serving thousands of kids and teens each day.

Understanding the Crisis

One year has passed since the Rohingya were forced to flee Myanmar’s western state of Rakhine. Most Rohingya are Muslim. They are a minority group in a country that is predominantly Buddhist. The Myanmar government considers the Rohingya to be illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, even though they have lived in Myanmar for centuries. The Rohingya face severe discrimination in Myanmar. The country denies them citizenship and basic rights.

On August 25, 2017, the Rohingya suffered a brutal assault by the country’s military. Thousands were killed. Those who survived sought safety in Bangladesh, crossing the Naf River and the Bay of Bengal in wooden fishing boats and makeshift rafts. Amena says she and her family escaped with little more than what they were wearing. “I was able to bring only two pairs of my clothes,” Amena says. “Nothing else.”

Around 700,000 Rohingya poured into southern Bangladesh, some 60% of them children. They joined thousands of others who had come in previous waves: The Rohingya have endured religious and ethnic persecution in Myanmar for many years. Today, the Cox’s Bazar district hosts nearly 1 million Rohingya refugees.

The Power of Art

People are working to help the Rohingya and raise awareness about their situation. One group is Artolution, a community-based public-arts organization headquartered in New York City. Artolution has worked with young people in more than 30 countries. In March, they were commissioned by UNICEF USA to set up a painting studio in the Oculus, a major train station and shopping center in New York City. There, some 200 people collaborated with Artolution cofounders Max Frieder and Joel Bergner to create a mural sending a message of support to Rohingya children.

In May, Frieder and Bergner took the mural to Bangladesh to permanently display it at the Balukhali CFS. Over a two-day period, Frieder and Bergner, along with eight local Rohingya artists and UNICEF USA staff, worked with Amena and other children to create a response mural to send back to New York. For many of the children, painting was a new experience.

“The first day, when the children saw the art materials, they became very interested, and excited too,” Tanzina Nasrin, a teacher at the CFS, tells me. “So the next day, when they got the chance to use these materials, they became really happy.”

In a phone interview from a project site in Israel, Frieder reflected on the mural-exchange project and its impact. “People need something that can bring joy amidst severe adversity,” he said. The project was, he says, a way of “utilizing the arts to access some of the really difficult experiences and challenges that these kids have been through.”

Likewise, he notes, displaying the children’s artwork in the United States helps Americans relate to the Rohingya refugee crisis. “It’s really important that people be able to see them as kids who are able to tell their stories through painting,” he says. “That’s one of our biggest goals: [to help] Rohingya refugees get their stories out to the world.”

As we sit together on the floor of the CFS, activity swirling around us, I show Amena a photo of the mural hanging in the Oculus, in New York. (It has recently been removed; UNICEF is in talks to install the mural at a new location.) She proudly points out her contribution: A smiling girl in peaceful surroundings. This is her dream for the future.

Waiting to Go Home

Amena and her fellow refugees do not know when or if they will be able to go home to Myanmar. On August 27, United Nations human-rights investigators called for top members of the country’s military to be prosecuted for genocide. Genocide is the intentional killing of a large group of people, usually those of a specific ethnicity, race, or religion. The investigators’ report says a deadly attack by Rohingya insurgents on Myanmar police posts did not justify the response by Myanmar’s military. They described Myanmar’s actions as “grossly disproportionate to actual security threats.” Investigators have urged the U.N. Security Council to refer the case to the International Criminal Court.

At a U.N. Security Council briefing in New York, on August 28, Secretary-General António Guterres said that despite a U.N. agreement with Myanmar allowing the Rohingya to go home, finalized in June, conditions are not in place for their safe return.

And so, Amena and her family wait at the crowded refugee camp in Bangladesh. “I feel happy to live here,” Amena says. For her and other Rohingya children, daily visits to the Child-Friendly Space help bring stability and joy in uncertain times. “And I am happy to come here.”