Among the roughly 2 million people living in Crimea when Russia annexed it earlier this year were several hundred intravenous drug users. Under Ukraine’s rule, they had been getting substitution therapy—typically, methadone or buprenorphine in place of opiates such as heroin—which is a widely accepted way of treating addiction in much of the world. But it’s illegal in Russia, where even needle-exchange programs to prevent the spread of disease are viewed with suspicion. As a result, drug users in Russia are at very high risk for HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis (TB), and get dumped in hospital TB wards in appalling conditions.

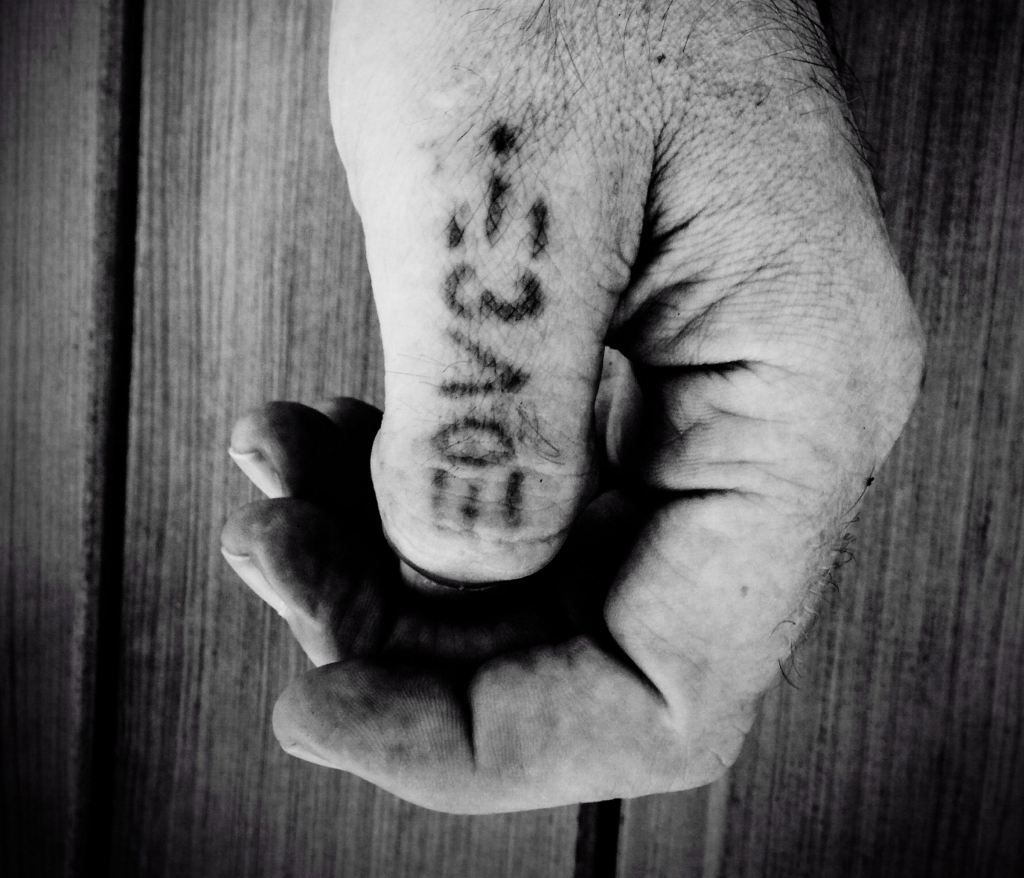

“Intravenous drug users are among the most vulnerable groups in Crimea now,” says photojournalist Misha Friedman. “But international NGOs are wary of taking on the problem because drug users aren’t like ordinary refugees. They’re complicated—very ill adults who’ve often spent decades in prison. Some money reaches them, but nobody knows what to do with them. And they don’t stay in one place like some other refugee groups, but are dispersed.”

Since the annexation, some of these people have stayed in Crimea and tried to wean themselves off drugs. Others have moved to parts of Ukraine still under Kyiev’s control, where they can get substitution therapy. But it’s become much harder for them to obtain their prescriptions and find work. Friedman, who visited Crimea in the summer, returned to Kyiv for Quartz last month and captured the plight of the people who, among all the losers from Russia’s annexation, find themselves at the very bottom of the pile. — Quartz Editor Gideon Lichfield

Click here to view the full photo essay in Quartz.