A kindergarten in Bristol puts an ominous sign on the door, warning parents of a scarlet fever outbreak. A Masters student in London is hospitalized with a rare strain of tuberculosis. An unvaccinated child dies of diphtheria for the first time in 14 years.

To many, these may sound like excerpts from a Dickensian novel—except they all happened in the UK within the last three years.

In a 2015 report by the Health and Social Care Information Centre, the staggering growth of these “Victorian” diseases is clearly displayed. The National Health Service (NHS) saw 4,883 cases of malnutrition between August 2010 and July 2011, increasing by 66 percent to 7,366 between August 2014 and July 2015. There were 82 cases of scurvy in 2010-11, but 113 in 2014-15.

Whooping cough cases increased from 272 in 2010-11 to 369 in 2014-15. Most drastically, 36 people were admitted with cholera in 2014/15—quadruple the nine cases documented between 2010-11. Public Health England reported 10,570 cases of scarlet fever in the 2015-16 period—with 1,319 new cases in just one week last March.

Dr Gerry Lee

Dr Gerry Lee is a nurse and senior lecturer at the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery in King’s College London (KCL). She first experienced these re-emerging diseases in 1987, when a high number of adult patients were left facing endocarditis [infection of the heart lining] as a consequence of having scarlet fever as children.

Nearly 20 years later, in July 2016, she was inspired to write an article for the International Emergency Nursing magazine based on the number of cases she is facing first-hand at the KCL hospital. She says that the re-emergence of these diseases is due to cuts in government funding and benefits, but also partly ignorance.

“We have got this elite arrogance," she says. "Look at us, we’re a first world country, we’ve got this much money—but in some ways we’re actually very health-poor… Part of what I wanted to show was this hidden epidemic… We really are going backwards.”

This is clear just from the list of diseases—scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, gout, whooping cough, tuberculosis and multi-drug resistant [MDR] gonorrhoea. These diseases were common in the Victorian era, caused or worsened by particular conditions that tend to be associated with poverty—lack of sunlight, overcrowding, vitamin deficiency and poor nutrition.

Lee adds, “Rickets is another condition that was never seen, the real bowed leg—something you’d find in the Indian subcontinent. There was a case at UCH [University College Hospital], probably eight years ago, of a child who had severe rickets and a lot of bruises.”

Doctors suspected child abuse, so authorities took the child into care. The mother, pregnant at the time, had her second child taken away at birth. The parents were taken to court and charged with abuse. Eventually, a pathologist diagnosed rickets and severe nutritional deficiency, explaining the bruising and bone deformities.

“But that was several years later, and the poor kids, the poor parents—what they’d gone through. So now the mood was: 'well hang on a sec, we need to educate people working in emergency departments and child services.'”

Lee prides herself on the educative part of her role. “We know from pathophysiology about the diseases, what the processes are, but we need to make it relevant to that patient… Because potentially they don’t care. When we’re talking to them, we’re focusing on the disease as if it’s the main thing that is happening in their life. Well, it’s not. They are maybe trying to stay married, look after their children… keep a roof over their head… Our priorities are health focused, when we should be life focused.”

No disease represents the relationship between lifestyle and medicine more clearly than tuberculosis—"the disease of the poor" according to Lee, who started working with TB patients while based at the London Chest Hospital.

She explains, “TB is basically a bacterium, mycobacterium, and you cough it up—so if people cough and don’t cover their mouths, which drives me nuts, then those droplets sit in the air and can be breathed in by someone else. The lungs are moist and warm and the bacteria spread. If not treated, they can cause cavities, so there are whole areas where the lung just stops functioning.”

If not caught at this stage, TB can cause night sweats, weight loss, lack of appetite and severe fatigue as the body fights the infection. Patients who are immuno-compromised are most at risk of developing TB—particularly HIV-positive patients, or those sleeping on the streets.

London has a particularly high TB rate. According to a London Assembly Health Report from 2015, “There were 2,500 new cases of TB in London in 2014, making up approximately 40 per cent of all cases in the UK… Some boroughs have incidence levels as high as 113 per 100,000 people—significantly higher than countries such as Rwanda, Algeria, Iraq and Guatemala.”

Find and Treat TB

In the shared fifth-floor kitchen of a University College Hospital building, Dr Alistair Story leans back in his chair against a vast picture window. He is the clinical lead at Find and Treat—an NHS-funded mobile clinic dedicated to diagnosis and treatment of TB among London’s homeless population.

Frustrated by the hospital-based model of waiting for patients to come to him, Story borrowed a van from Rotterdam, “stuck it on a ferry” and started diagnosing the disease in the areas and populations he knew it was most rife.

He smiles, “There’s two kind of TB patients, if you want to be simplistic about it. There’s patients who recognize the symptoms, present to clinics, take their treatment and say thank you very much and bugger off. And then there’s patients who don’t.”

It is this latter group that Find and Treat are fighting for. “We’re working with a population who are invisible when it comes to routine health statistics. You walk into an A&E [Accident and Emergency department] and you’re not documented as homeless… You die, your death certification — not documented as homeless. One of our challenges is to make this invisible population visible when it comes to their health needs.”

And this only refers to those who go through the NHS system. Officially, the UK has actually experienced a reduction in TB cases, from 7,528 in 2011 to 5,457 in 2015, with London responsible for 39.5 per cent of the decrease. But this is not the situation that Find and Treat are experiencing.

Story says, “We know from our own screening work that there’s a very high prevalence of undetected active TB in the [homeless] population. In fact, a staggering prevalence of undetected active TB—about 1 in 5… You can’t measure the health of a population from the perspective of those who use health services.”

In fact, the biology of TB makes it hard to obtain accurate statistics or measure trends at all. Story laughs, “TB is a bit of a pain in the ass. We don’t really understand the etiology… But in a nutshell, TB is a slow burner. If we did have a serious problem that was “brewing” in that increasing cohort of people on the street, we probably wouldn’t see it in the same way as we’d see a spike in influenza, or a disease that has the common decency to have a reasonably predictable epidermic curve.”

The patients, and their living situations, are equally unpredictable. Yasmin Appleby, a TB nurse specialist at Find and Treat, explains some of the complications clients face. “They’re chaotic, their lifestyle is all over the place, they show up after 5 o’clock, they run out of meds, they lose their meds… One of the biggest things for me, it’s the relationship you develop with someone, it’s that trust you form. It’s a real key part to getting someone through treatment.”

Story adds, “One of the worst mistakes most of the people we work with have made in their lives is having poor parents, and there’s not much they can do about that.”

This sporadic lifestyle can lead clients themselves to exacerbate the spread of the disease. Story explains, “I don’t use the term “super-transmitter” very lightly, but the reality is you’ve got an individual who is highly infectious but otherwise reasonably fit and healthy and able to soldier on despite the quite staggering debilitating effects of having massive cavities in your lungs… coughing their guts up, not recognizing the symptoms because they’re masked by the substance use and alcoholism and lifestyle factors, but most importantly being in a very confined airspace with individuals who are equally immunocompromised.”

On the van

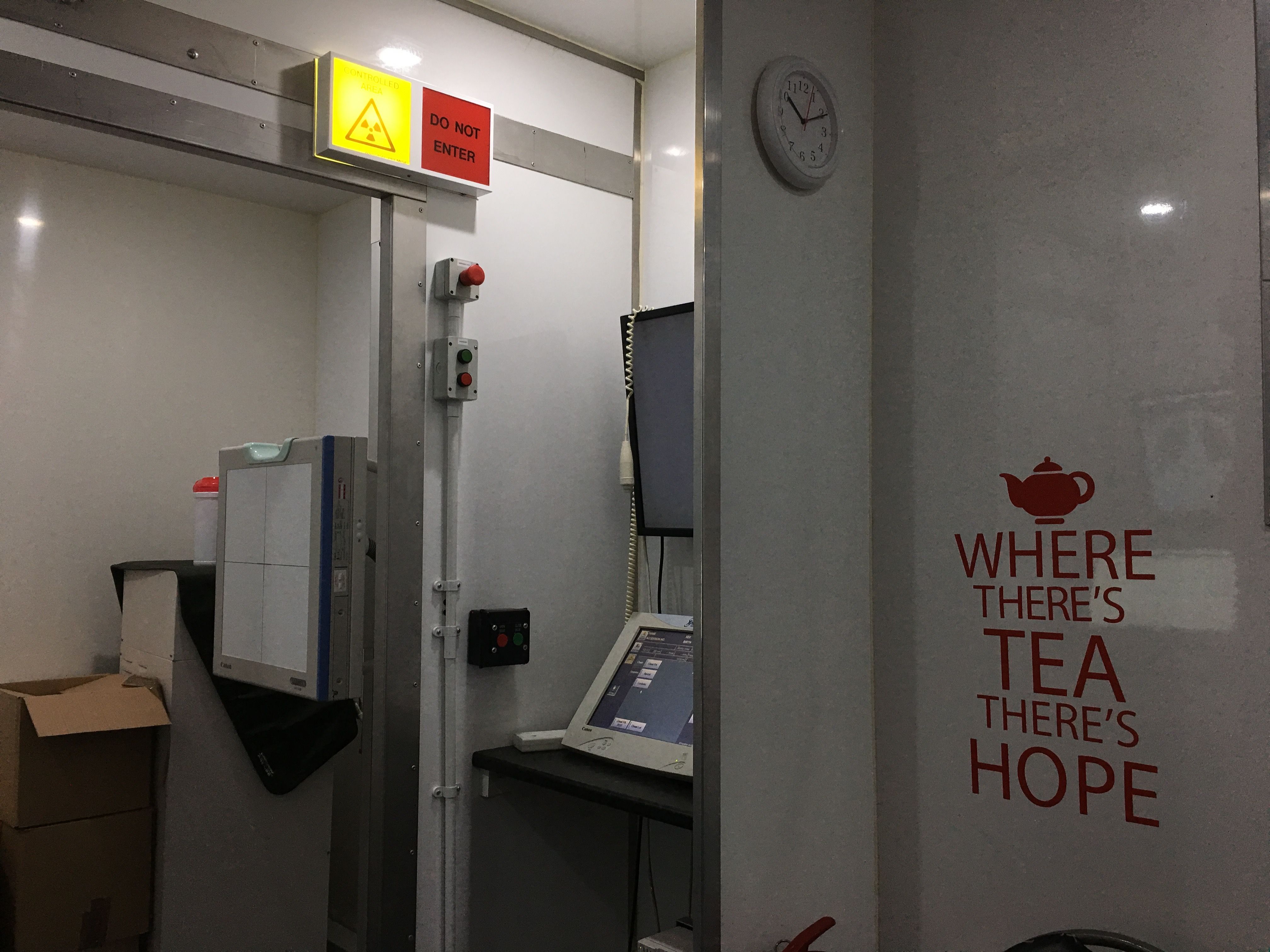

On the van, the world of office chairs and picture windows is distant—though there is a “kitchen” in the form of a kettle on the floor. The van is narrow, but bright and surprisingly non-claustrophobic considering the amount of equipment and medical professionals crammed in.

It is the week before Christmas, and the van is located halfway down a shadowy side road just off Oxford Street. The front of the van, with ‘FIND AND TREAT’ emblazoned in red, is illuminated by the glare of Christmas lights. There is a buzz of activity around the tiny entrance, with a crowd of volunteers from various organizations donned in warm scarves, ready to go and recruit clients.

The van literally shudders with an electrical surge as the generator clicks and whirs into action. The process inside is fairly simple: Patients are brought onto the van and sit by a desktop computer to provide basic information. They are then taken into a lead-lined compartment at one end of the van, where they place their chest against the X-Ray machine and an image is taken. Results and, if necessary, referrals are immediate: one radiographer remembers one case so severe she had to rush the client to A&E in her own car.

The hum of different languages being spoken simultaneously by clients and volunteers highlights a new issue for the team: communication with—and perception of immigrants. Find and Treat has accumulated a network of friends and confidants who can help overcome language barriers, according to Phil, a long-term employee and today’s van driver.

He explains, “We’ve always tried to get away from the whole ‘it’s the immigrants bring it all in’—however most of the names on our database are not UK-born. We’ve always tried to make the case that it’s lifestyle, not ethnicity—it’s not because you’re from Somalia, it’s because you’re homeless and an alcoholic.”

Story adds, “It’s re-stigmatization. Everything’s linked isn’t it? The more right wing, xenophobic politics that are being peddled by our current government have really eroded any sense of enlightened self interest. It’s back to blame, it’s back to deserving or undeserving poor. The Victorian analogy was very much around assessing people to see if they were morally permitted to exist in this state of poverty, or whether their predicament warranted some kind of charitable response.”

Back on Oxford Street, crowds begin to dwindle, the van is packed up, and the team prepares to do it all again — in less than 12 hours time. Until a more systematic, permanent change can be implemented, Find and Treat will be there.