When Daniella Zalcman visited Canada for the first time in 2014, she was shocked by the poverty and desperation she witnessed in parts of Saskatchewan's indigenous community.

The photographer captured scenes of neglected homes against stark, rolling landscapes, and she encountered weary individuals ravaged by alcoholism and addiction.

Nearly everyone she spoke to passed through the residential school system, a dark chapter in Canadian history that was the government's form of cultural assimilation. The government-funded, church-run schools, which started in the 1870s, attempted "to kill the Indian in the child." More than 150,000 First Nations, Metis and Inuit children were taken from their families and placed in schools across the country, where they were forbidden from speaking their language or practicing their culture.

The schools began closing in the 1980s, and the last school closed in 1996 amid reports of sexual and physical abuse. The Canadian government made its first formal apology for the residential school system in 2008, and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission officially labeled it "cultural genocide" in 2015.

"They created a new way of subjugating and marginalizing people; they were essentially trying to wipe out the indigenous community," Zalcman said.

As she dug deeper into the history of these schools and listened to people's stories of physical, emotional and sexual abuse, she realized her photographs barely scratched the surface. She returned to Saskatchewan last year and spent three more weeks taking portraits.

Images from the two trips culminated in "Signs of Your Identity," winner of the 2016 FotoEvidence Book Award. The title references the formal apology from the Anglican Church, which operated many of the residential schools along with the Catholic Church: "I am sorry, more than I can say, that we tried to remake you in our image, taking from you your language and the signs of your identity," Archbishop Michael Peers said in 1993 (PDF).

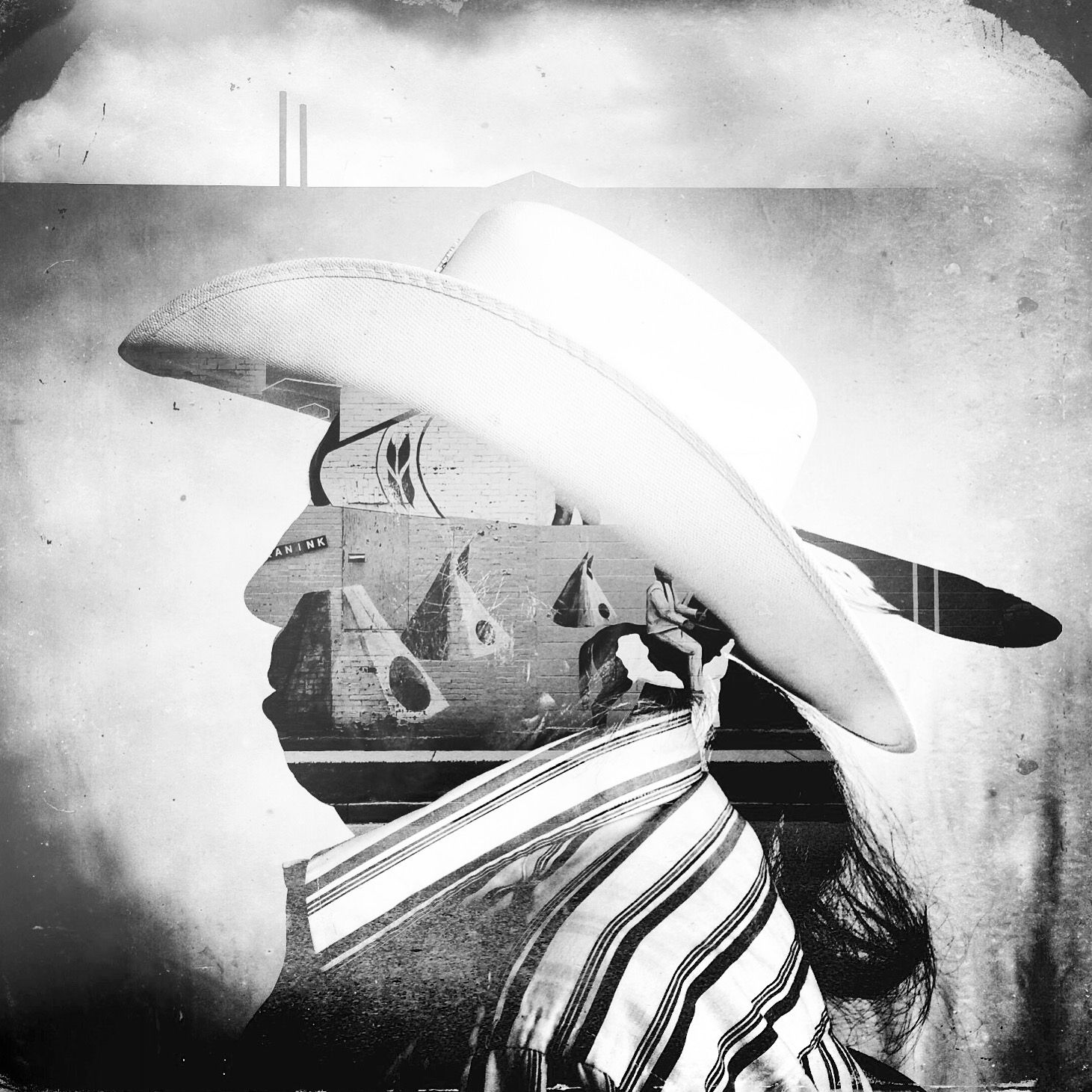

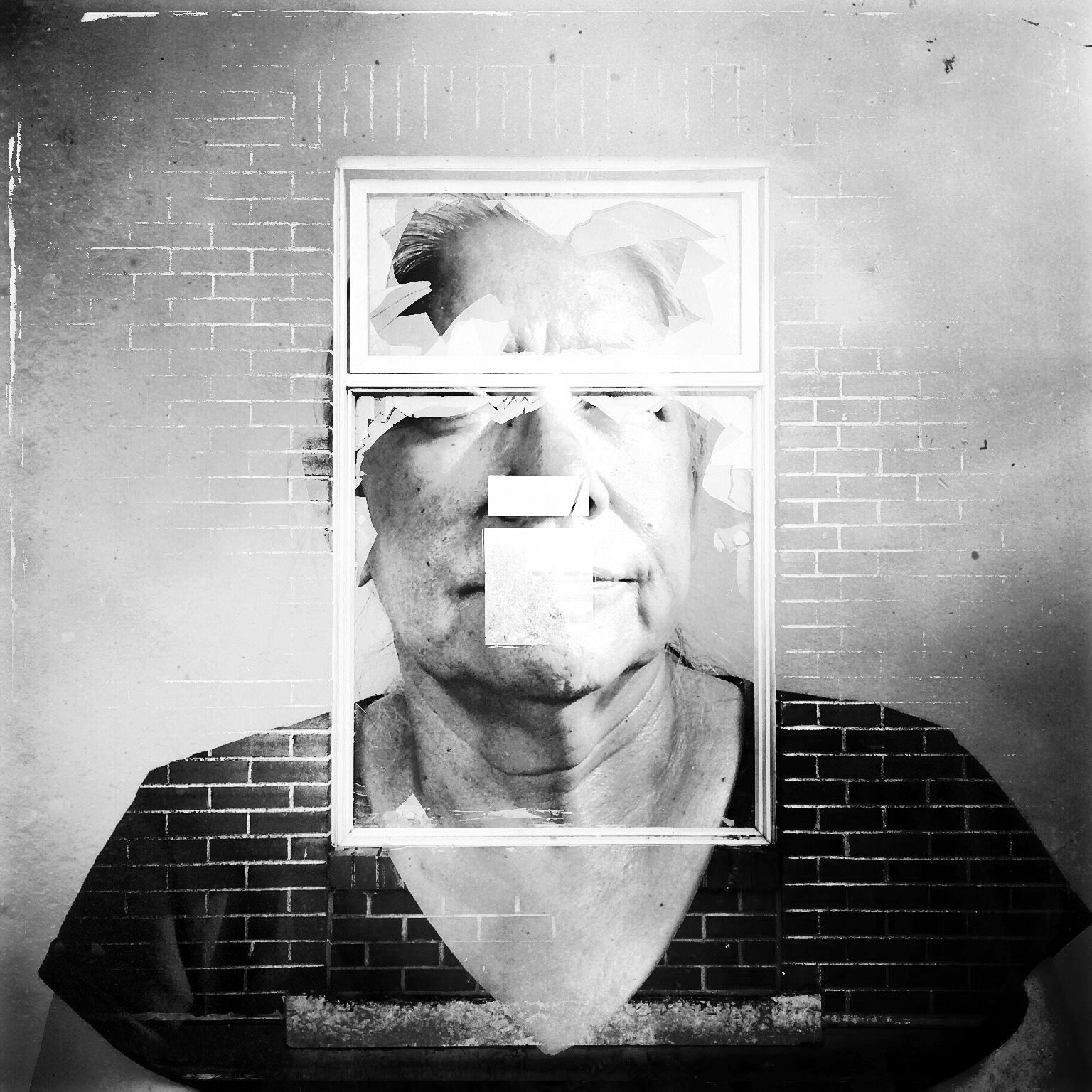

For her project, Zalcman used double-exposure portraits, juxtaposing people against sites of the former schools to create meditations on memory and the psychological legacy of the schools.

The idea came about while Zalcman was at an AIDS conference in Australia, another country that has gone through the truth and reconciliation process with its indigenous community. She was stunned to learn that Canada's First Nations people had one of the highest-growing rates of HIV in the world, despite the country's reputation for pioneering needle exchanges and other harm-reduction strategies.

"I believe these public health crises that the First Nations community is facing now is the direct result of the legacy of these residential schools," she said.

Most of the 45 people she spoke to attended two schools in Saskatchewan from the 1950s and 1970s, a documented period of intense sexual and physical abuse. Students at George Gordon First Nation, north of Regina, were sexually abused for decades.

Other subjects attended Beauval Indian Residential School in Battleford, where at least one person has been held accountable for numerous instances of sexual abuse.

Zalcman was astounded by their vivid memories, as if they'd been waiting to tell their stories. She felt ashamed that their stories had been excluded from the history books.

"When we collectively think about the awful things done to the Native American, we talk about things that happened hundreds of years ago," she said.

"This is modern history."

This article was written by CNN's Emanuella Grinberg.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 4.88 KB |