BELÉM, Brazil—A revolving door of doctors misdiagnosed all of Denise Almeida’s symptoms. The patch on her back was not a fungal infection, the swelling on her ear was not edema, the mark on her abdomen was not a heat rash and the bumps on her foot were not hives.

It was the fifth doctor that read it right—Almeida had leprosy.

“All of those little symptoms crushed my spirit. I was so afraid of dying,” Almeida said. “The worst part is that I went to the doctors and I went to the clinics. I tried to help myself, but I suffered from neglect.”

In contrast to global trends, Brazil has seen a steady rise in new leprosy cases over the last two years. While leprosy is curable with intense multidrug therapy, the biblical infectious disease can cause disfiguring skin sores and severe nerve damage if left untreated.

“I used to dance, but leprosy took all my beauty and all my strength,” Almeida said. “When I began the treatment I could barely stand, I couldn’t even get out of bed. Every part of me ached.”

Brazil, the largest and most populous nation in South America, is the only country in the world that has not reached the World Health Organization’s leprosy elimination standard of one case per 10,000 inhabitants. This has left an unknown number of Brazilians untested, or like Almeida, misdiagnosed.

Pockets of leprologists are trying to reverse the increase of cases by improving medical training and developing new ways to track the disease, which passes through regular physical contact and respiratory droplets. One of the most critical components of curving the increase of cases is more extensive testing.

Dr. Claudio Salgado, Almeida’s fifth doctor, is a veteran leprologist and the president of the Brazilian Leprosy Society. Since joining the organization more than a decade ago, he’s witnessed a steady decline of leprologists.

“Trained leprologists can diagnose cases early, prescribe the correct treatment, work with patients to improve home hygiene and go through the correct methods to test others exposed,” Salgado said. “By missing one of those elements untrained professionals can make a situation much worse.”

Lack of Leprologists

In a country where nearly 30,000 people a year are diagnosed with leprosy, the Brazilian Leprosy Society has certified just over 100 leprologists—which is less than one certified leprologist for every 100,000 people in the country.

These specialists are on the frontlines of the resurgence of leprosy.

According to Brazil’s Ministry of Health, from 2016 to 2018, the number of new cases rose from less than 25,300 to more than 28,600—the first rise in cases in over a dozen years. Carmelita Ribeiro Filha, the coordinator of the Leprosy and Disease Elimination Program for Brazil’s Ministry of Health, declined to comment on this trend.

According to Salgado, one of the leading reasons the disease has not been eradicated in Brazil is because of untrained medical professionals who fail to diagnose it.

After a cascade of ineffective pills from unspecialized doctors, Almeida traveled to the city of Marituba—home to the Center of Dermatology and Salgado’s Laboratory of Dermatology-Immunology.

“Every time I spoke to Marituba patients, they all said they were first diagnosed with other issues. I mean, Jesus Christ, it’s just different people with the same history as me,” Almeida said. “If they had diagnosed it correctly, they would have changed my history. Everything in my life and my children’s lives could have been different because they would have had a healthy mom.”

Even when physical symptoms appear, like the ones Almeida had, leprosy can still be easily confused with other common infectious diseases in Brazil.

Shorthanded leprologists often depend on dermatologists for assistance.

These skin doctors would generally be able to identify an infectious disease and refer the patient to a leprologist. But in Brazil, the lack of leprologists is paired with the scarce distribution of dermatologists.

Only 9.5 percent of the nearly 5,600 municipalities in Brazil have a resident dermatologist, according to the Brazilian Society of Dermatology. As of last year, the society had certified fewer than 10,000 dermatologists for Brazil’s population of more than 209 million.

“The only solution is to train more people to deal with leprosy and make sure that they are where they need to be,” Salgado said.

To begin a national effort to effectively combat the disease, the Brazilian Leprosy Society estimates the country would need at least 2,000 more doctors to go through leprology training and pass the specialist certification examination.

“If we can get one leprologist into almost half of the municipalities, we can build a framework of aid. This framework could keep people from falling through the cracks and give them the medicine they need when they need it,” Salgado said. “We will still be spread thin, but we could do a lot more good.”

Salgado’s work with the Laboratory of Dermatology-Immunology is based in the northern state of Pará, which has seen more new cases of leprosy over the last 25 years than any other state in the country.

Every semester at the lab, Salgado mentors graduate students from the Federal University of Pará, the largest medical institution in the state, where he is also a professor of pathology and immunology. But over the years, he has seen a steady decline in student interest.

According to Salgado, one of the reasons there are fewer leprologists is because universities across Brazil no longer prioritize infectious diseases in their curricula. Even at Salgado’s institution, staffing changes were the direct result of a shift in the disease’s numbers.

“The number of new cases went down and because of that, so did our focus. They removed our leprosy chair and all those classes were transferred to other departments,” Salgado said.

Alzira Rodrigues, who worked in several leprosy colonies across the state and now has her own dermatology practice, was the university’s last leprosy chair.

“The more we teach, the more people can go into the field with the knowledge to find and treat leprosy patients. … More attention needs to be given to the emergence of this disease and we need more specialists,” Rodrigues said.

Salgado and other professors in his department are trying to reinvigorate student interest in studying diseases such as leprosy by the end of 2020.

“We are trying to open a chair of neglected diseases to call attention to diseases like leprosy, leishmaniasis, and tuberculosis,” Salgado said. “We want to show our students that neglected diseases just mean neglected people.”

Doctors in the Dark

With a decline in student interest and a lack of specialists on the field, Salgado expects the number of annual new cases in Brazil to continue to rise. He estimates a more accurate number of new cases in Brazil would be closer to 100,000—more than triple the government’s most recent estimate.

Whether it be by human error or lack of resources, more than four million leprosy cases globally are expected to be left undiagnosed between 2000 and 2020, according to a study by the journal of Neglected Tropical Diseases.

“We aren’t properly testing people on a national level. If we’re not doing that how can we have faith in our national numbers,” Salgado said. “As doctors, our work is only made more difficult when we can’t rely on the official data being given to us. How can we be expected to eliminate leprosy if we have no idea how widespread the problem is.”

Over the last decade, the Laboratory of Dermatology-Immunology has been working on its own analysis of leprosy cases in Pará.

The lab has conducted dozens of surveys across multiple cities, including Marituba, to locate leprosy outbreaks. Approximately 8 percent of the 15,155 residents examined have tested positive.

“The fundamental aspect of eliminating leprosy is prevention,” said Josué Pompeo, the secretary of health in Marituba. “When we find new leprosy cases we need to make a clinical examination of all household contacts. If we don’t do that, we will continue missing patients.”

Similarly, to the current COVID-19 pandemic, mycobacterium leprae—the bacteria that causes leprosy—is transmitted by direct contact with airborne droplets that can pass from person to person through exhales, coughs, or sneezes. Leprosy’s average five-year incubation period allows an undiagnosed individual to easily spread the disease undetected.

Spatial epidemiology, the study of a disease’s geographic spread, has been used to track outbreaks because the likelihood of leprosy infection increases with proximity and decreases with distance.

Dr. Josafá Barreto works at the Laboratory of Dermatology-Immunology and leads the lab’s efforts to track new leprosy clusters.

“When we diagnose a new leprosy case, we have to test all of those that have been exposed. We track all new cases to see patterns in the outbreak,” Barreto said. “But it’s just not enough. This isn’t being done on a national scale. Even though we are tracking things here, the rest of the country is still in the dark.”

Any delay in diagnosis can allow leprosy to develop into a Grade 2 case, which is the disease’s most severe stage. While multi-drug therapy developed in the 1980s and 1990s has dramatically curbed the number of global leprosy cases, the disease can still cause permanent nerve damage and disfigurement, especially at this stage.

Without definitive national data to focus the efforts of leprologists, the number of severe cases has also been on the rise. Approximately 8.5 percent of new cases diagnosed in 2018 were showing Grade 2 severity—a nearly 2 percent increase since 2014.

“Neglected diseases, like leprosy, are bad for everyone. It’s not just an issue for countries. It’s an issue for humanity. To have healthy people in all societies is a goal we need to strive for,” Salgado said. “The time has passed for people to still be struggling with leprosy. We need to stop it.”

Road to Recovery

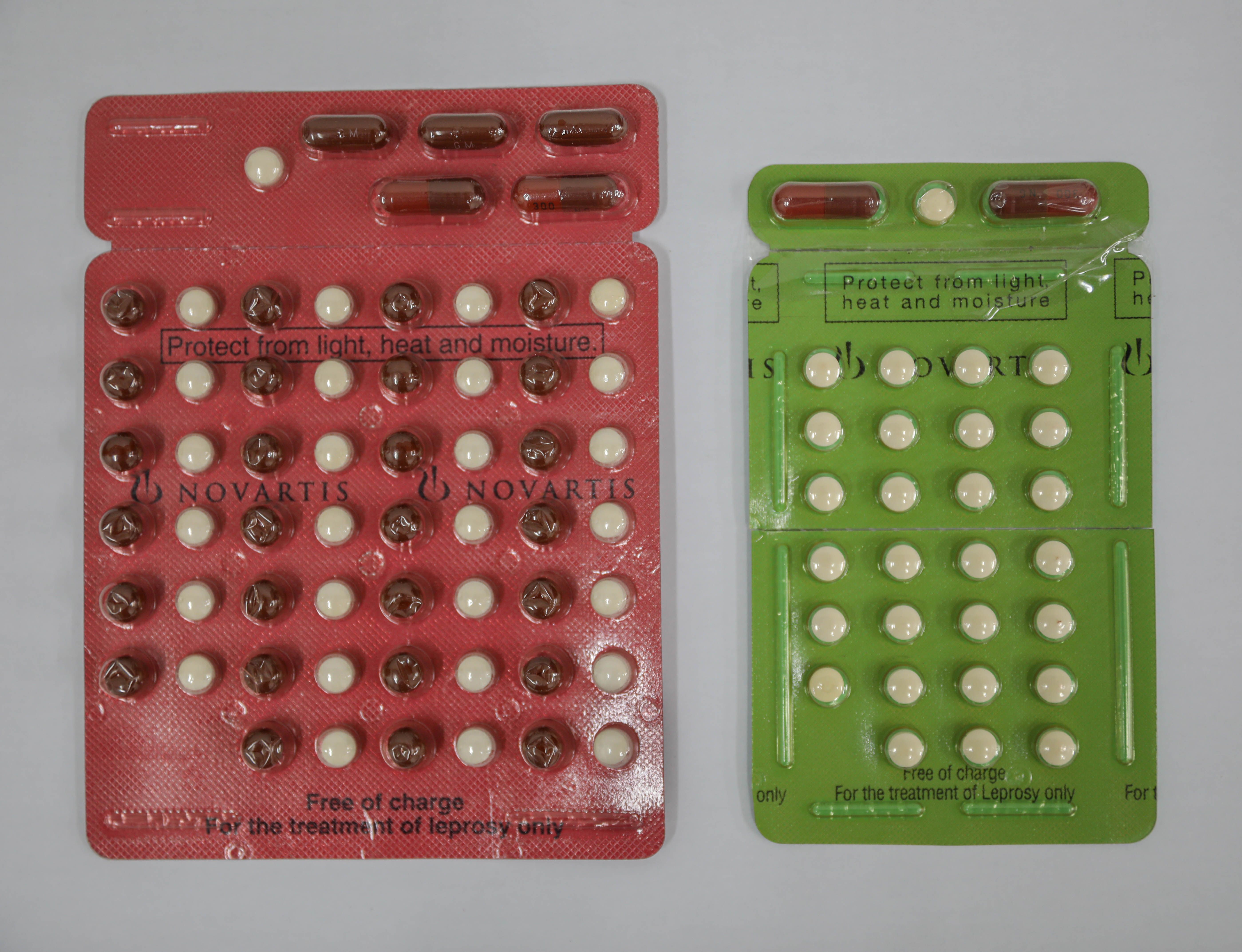

Almeida still takes a pill every morning, afternoon, and evening as a part of her multi-drug therapy. She is only a few months into her new treatment, but she is no longer considered contagious. According to data from the Ministry of Health, more than 30,000 Brazilians are on multi-drug treatment for leprosy—a nearly 10,000-person increase since 2015.

“When I was diagnosed I didn’t even want to stay near my children or my husband. I was so angry at everything leprosy took from me, but now it’s coming back,” Almeida said.

Almeida, now 24, lives with her husband, three children, and mother. She is hoping to find a job by the end of the year and reintroduce a sense of normalcy into her life.

“I’m fortunate because I haven’t walked away with a disability, but many of the people I knew in Marituba did, and they’ve been struggling to find work,” Almeida said. “It’s difficult to go back to having a regular life after leprosy. Our faces and bodies suffer with the disease.”

The physical marks leprosy left on Almeida’s face and body are beginning to fade. She prays it will soon just be a memory.