Kenya has become a model country for laws that help protect girls from female genital mutilation (FGM). But advocates say, after almost a decade, that law alone is not enough to stop the harmful practice.

Sophia Leteipan, a prosecutor in Kenya says the federal 2011 Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act is not enough to end the practice because of the “lack of evidence” that makes it difficult to prosecute offenders in court.

Many Kenyans, despite the law, remain unwilling to report that FGM occurs in their communities—making arrests and prosecution difficult because police and government officials don’t want to interfere with the culture.

“It’s very rare that community members will snitch on other community members because it’s their families, it’s their grandmas who are doing the cutting,” Leteipan said. “It’s very unusual to find people within that community where FGM is happening.”

Equality Now, a non-government international organization that advocates for the rights of girls and women, agrees.

When somebody has been reported by a community member for female genital cutting, “they disappear from the community," said Felister Gitonga, Equality Now Program officer.

“This is where the biggest challenge begins when it comes to finding concrete evidence,” she added.

Leteipan says one of the issues that prosecutors face when they have a case is figuring out what would happen to children whose parents have been arrested for allowing them to undergo female genital mutilation. Often, according to Leteipan, a judge will drop a case for fear that the children won’t have anyone to take care of them if their parents are jailed.

FGM—the full or partial removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons—is usually done secretly by professional cutters. The practice has long roots in the history of some tribal communities in Kenya.

“When we go to these communities, we realize that this is a practice that has been there for hundreds of years,” said Gitonga. “It takes a lot of education . . . for them to change the practice.”

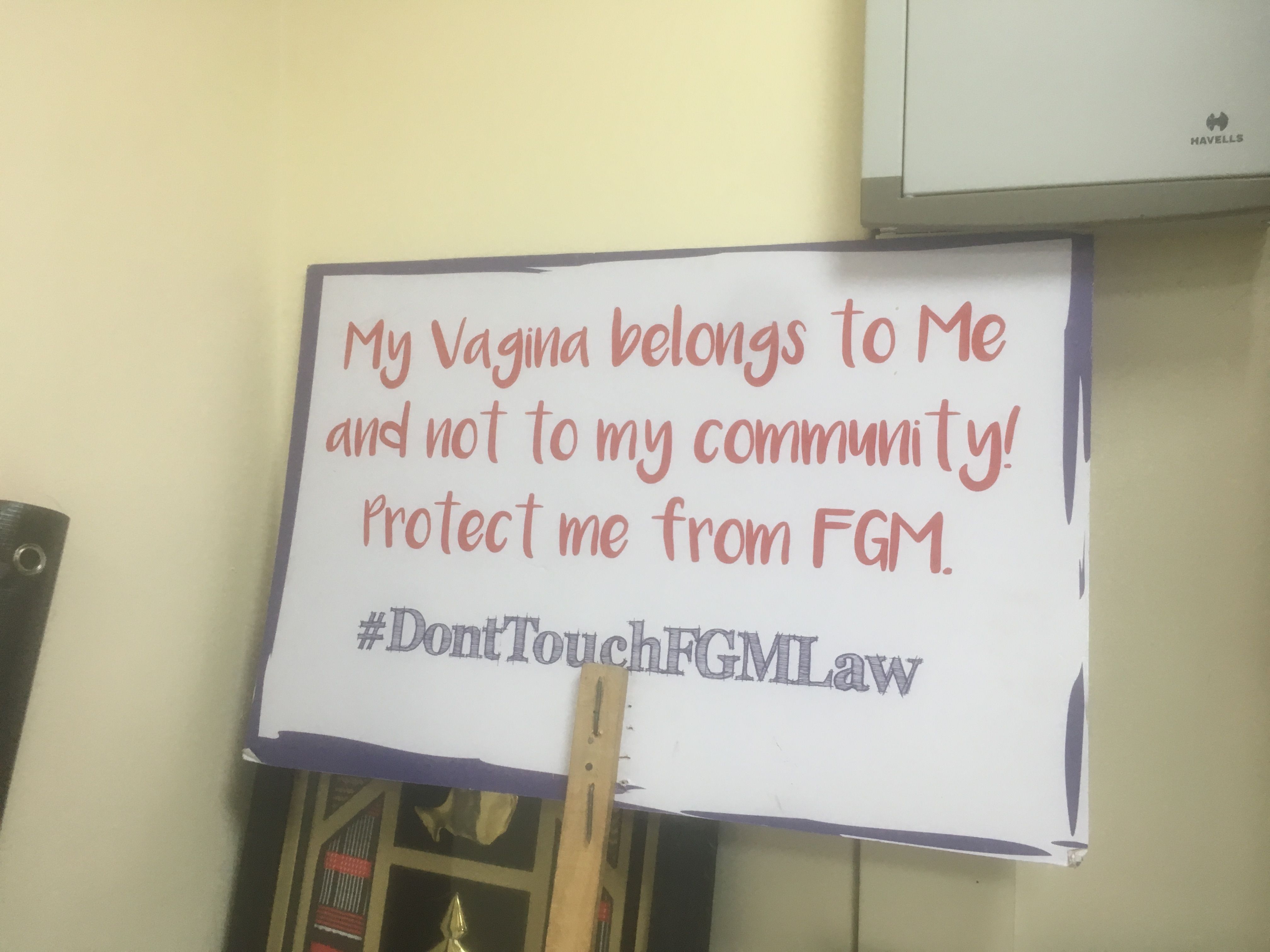

Often, girls in communities that practice the cutting believe that in order to be accepted in society, they have to undergo the cut, Gitonga said. She argues that even if young women request the cutting, they are not consenting of their own free will.

The federal anti-FGM law that was passed in 2011 made it illegal for anyone to perform or allow the practice to happen. Failure to report the practice can lead to being fined or jailed.

UNICEF reports that at least 200 million girls and women in 30 countries worldwide have undergone FGM.

It took the powerful voice of a survivor and the request of a determined member of parliament to see that the law passed.

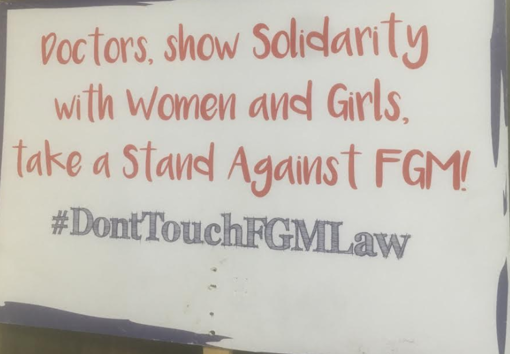

Linah Kilimo comes from a community that has long practiced FGM. When she joined parliament in 2003, she said she knew she had to “do something.” She joined forces with another parliamentarian Sophia Abdunull to encourage victims to share their stories in parliament. They also brought gynecologists to parliament to explain the medical effects of FGM.

“It’s not easy convincing communities to abandon the norm. However what we tell them are the consequences of FGM,” Kilimo said.

Although there are some challenges with the law, Kilimo recommends one solution that she believes might help.

“You won’t be in jail, but you’re going to be given some type of punishment to make up for what you did.” Kilimo said.

No matter what the future holds or how the law is changed, there is a generation of girls who have already undergone the practice—many of whom suffer medical complications. Dr. Adan Abdullahi, who treats FGM survivors, said they can face long-term medical complications, and many of them struggle emotionally.

“They feel less of a woman because of the psychological trauma. It’s a huge mental torture for these women,” Abdullahi said.