Like so many of Mao’s pronouncements, it sounded simple. “The South has a lot of water; the North lacks water. So if it can be done, borrowing a little water and bringing it up might do the trick.” And thus, in 1952, the spark was lit for what would blaze to life four decades later as China’s most ambitious engineering project—a scheme to bring some 45 billion cubic meters of water, mostly from the mighty Yangtze and its tributaries, up to the north China plain to Beijing and the parched farmland and factory towns around it. The central route of the project began carrying water from Hubei to Beijing in late 2014, and, like so many of Mao’s plans, it has left a swath of human devastation in its wake.

Most environmentalists see the South-to-North Water Transfer Project as a necessary, though not sufficient solution to the severe water shortages suffered in China’s capital and surrounding areas—a situation that owes much to weather and climate but which has been compounded by the over-damming of the region’s rivers (another of Mao’s enthusiasms) and the severe pollution of its already small supply. Without comparably ambitious plans for regulation and conservation, experts like Ma Jun have been saying for more than a decade, those 45 billion cubic meters are just a drop in the bucket. And the project has put its own stresses on the environment, even as it has alleviated others.

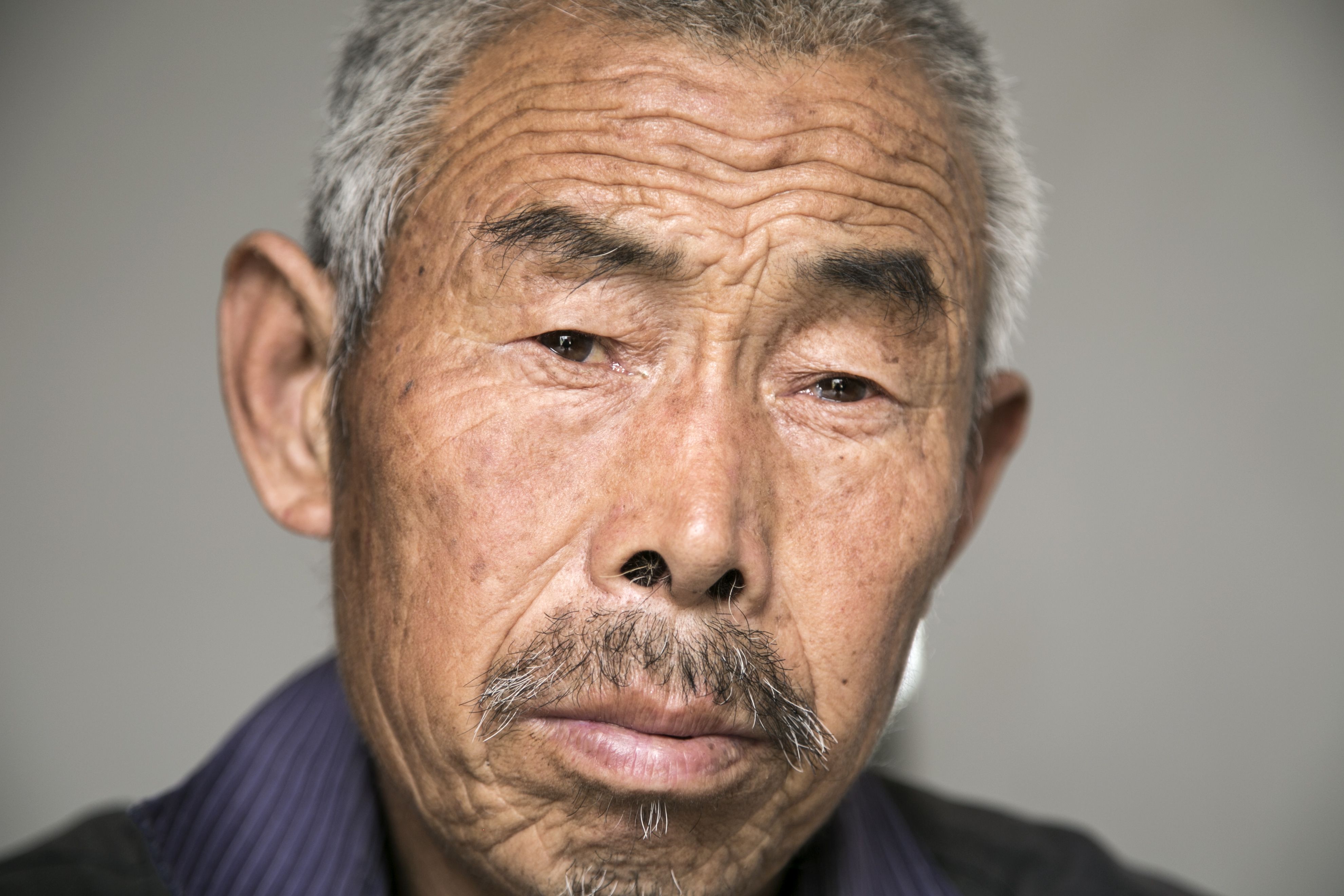

On the winning end are residents of Beijing’s ever-sprawling suburbs, hoping for reliable showers and clean water to cook with. On the short end of the stick are the people who live in the areas giving up their water, who, without choosing to have had to leave their homes, find new work, leave behind the comforts of community and family, and fathom how their lives fit into the grand and ambitious plans their leaders have devised to solve a nation’s problems.