October 17, 2013 | Pulitzer Center

By

Alia Malek, for the Pulitzer Center

Many of the ethnically Armenian Syrians who fled to Armenia to “wait out the violence” in Aleppo, where many Syrian Armenians live, ended up in Yerevan, the capital and largest city. Although most say they plan to go back to Syria as soon as possible, the government of country of Armenia has received them and sought to help them as they have requested. This includes sending aid back to Armenians who did not have the means or desire to leave. It also includes allowing Syrian Armenians to open their own school that follows not the Armenian curriculum but rather that of Syria. As a community Syrian Armenians have tried to maintain neutrality in the spiraling conflict, afraid of retaliation from either the Assad regime or whoever replaces it.

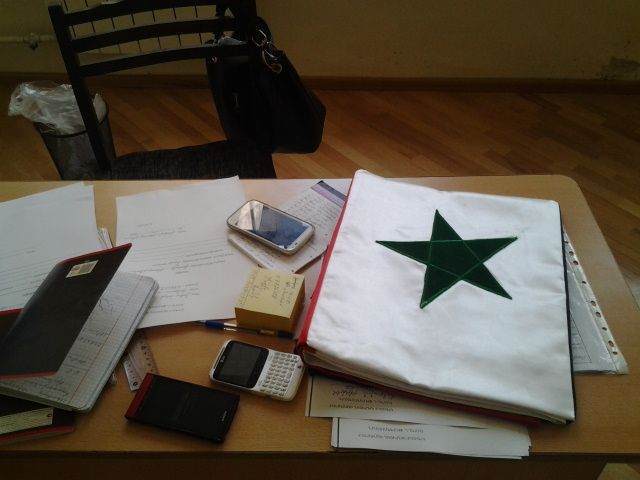

![A member of parliament tasked with overseeing the aid effort dictates a note to be attached to each box of aid. It reads: “From the people or Armenia and Artsakh [Karabakh] to the brothers in Syria via the Armenian Church.” Image by Alia Malek. Armenia, 2012.](https://legacy.pulitzercenter.org/sites/default/files/styles/node_images_768x510/public/03-29-13/8.jpg?itok=rYYbdvNT)