If I hadn’t been following the news, I would have thought that the entire city of Oxford, UK had collectively come down with the flu on the morning of June 24. Every person I encountered that morning—friends, professors, shopkeepers, Massoud who runs the city’s most popular kebab cart—bore the same sickly expression.

As an American studying in the UK, I had been following the EU referendum fairly closely, but like many of my contemporaries, I never really considered the reality of Brexit before I woke up that morning.

Living in Oxford in the lead up to the referendum, I had not experienced Brexit as a contentious topic of debate—Remain won the city by an overwhelming majority, a consensus reflected in the popular discourse. When the Oxford Union debating society brought in political leaders including UKIP’s Nigel Farage and former Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg to make both cases to students, the ‘leave’ motion mustered only 73 votes, compared to nearly 300 in favor of remain. And the Union debate was one of the only times I encountered the issue framed as a binary choice. While Brexit featured prominently in both casual conversations and University lecture series, the question was intellectualized and abstracted: "how did we get to this point," "what does this say about British politics today," "what’s next for the Conservative party." The implicit assumption was that Brexit was a bout of temporary insanity and sentimentality run amuck—while the vote might be close, there was never any serious doubt as to what side would prevail.

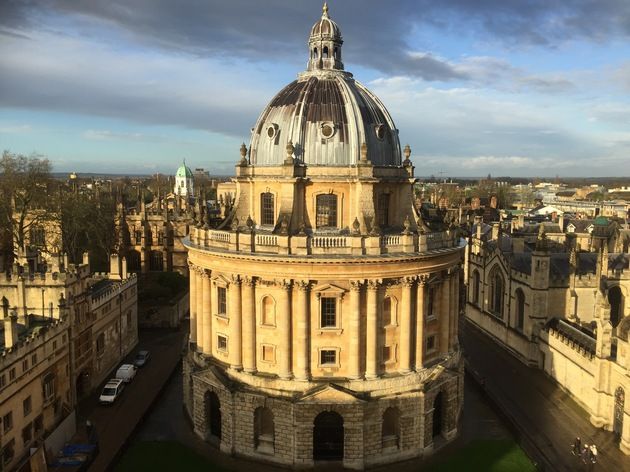

When I talked about Brexit with my friends, we were throwing opinions into an echo chamber. Within this bubble we failed to anticipate the consensus within our own social and academic circles could so sharply diverge from sentiments elsewhere in the country. An uncharitable interpretation of this phenomenon would pin our blindness on the elitism of Oxford and its students—reflective of a broader disconnect between the elite and non-elite of British society. Certainly there is much truth to this. Oxford is educated, affluent and international. It’s also one of the least affordable cities in the United Kingdom: the housing market makes it difficult for most people to move to Oxford and continuously pushes out those who cannot afford to stay. Post-referendum statistics indicate that education level and income were key fault lines along which the Brexit vote fragmented, factors that make Oxford’s outcome unsurprising.

Yet there is a secondary force at play as well. Those most shocked by the results both in Oxford and beyond were my peers—the 20-somethings who overwhelmingly voted to remain across class and income strata. 73 percent of those aged 18-24 voted to stay in the EU. Remain also won the next age bracket, 25-34 with almost two-thirds of the vote. Still, despite polling indicating that these results are largely representative of youth sentiment, turnout amongst young people remained low. Given the UK’s high median age and overall high referendum turnout, it is unclear whether or not the youth vote could have changed the results, but these voices were certainly underrepresented in the outcome.

No one knows what will happen next, but there is little question that the generation most opposed to Brexit will be the generation who disproportionately bears the brunt of its consequences. My dissertation advisor just bought a home, which already is rapidly depreciating in value. My friends who are about to graduate can no longer be certain if there will be jobs for them in the UK, or if companies will fly to greener pastures in other European cities like Frankfurt. My continental European friends might not be able to stay in Oxford to complete their degrees.

But while this sort of fallout was anticipated—albeit avoidable—talking to my stunned British friends the day after the referendum, I realized that the blow struck more than calculations of rational self-interest. Being European is part of their identity. Born and raised in a globalized world, their expectations are global. To wake up to Brexit was a shock not merely to their hopes of future employment opportunities or income potential, but also to their sense of self. While the issue has largely been framed as a case of nationalist sentiment trumping reason, I fear that this fails to account for the response of a generation whose very identity was rooted in a sense of Europeanism — without which they must now navigate an increasingly uncertain landscape.