Production of this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and IHE Delft Global Partnership for Water and Development

Otewu John never thought he would end up in a life of crime.

But when the 56-year-old’s garden of 20 years was slashed and he was forced from the land, he found himself resorting to illegal fishing, lacking the small amount of money needed to invest in a more expensive legal fishing net but needing to provide for his 9 children.

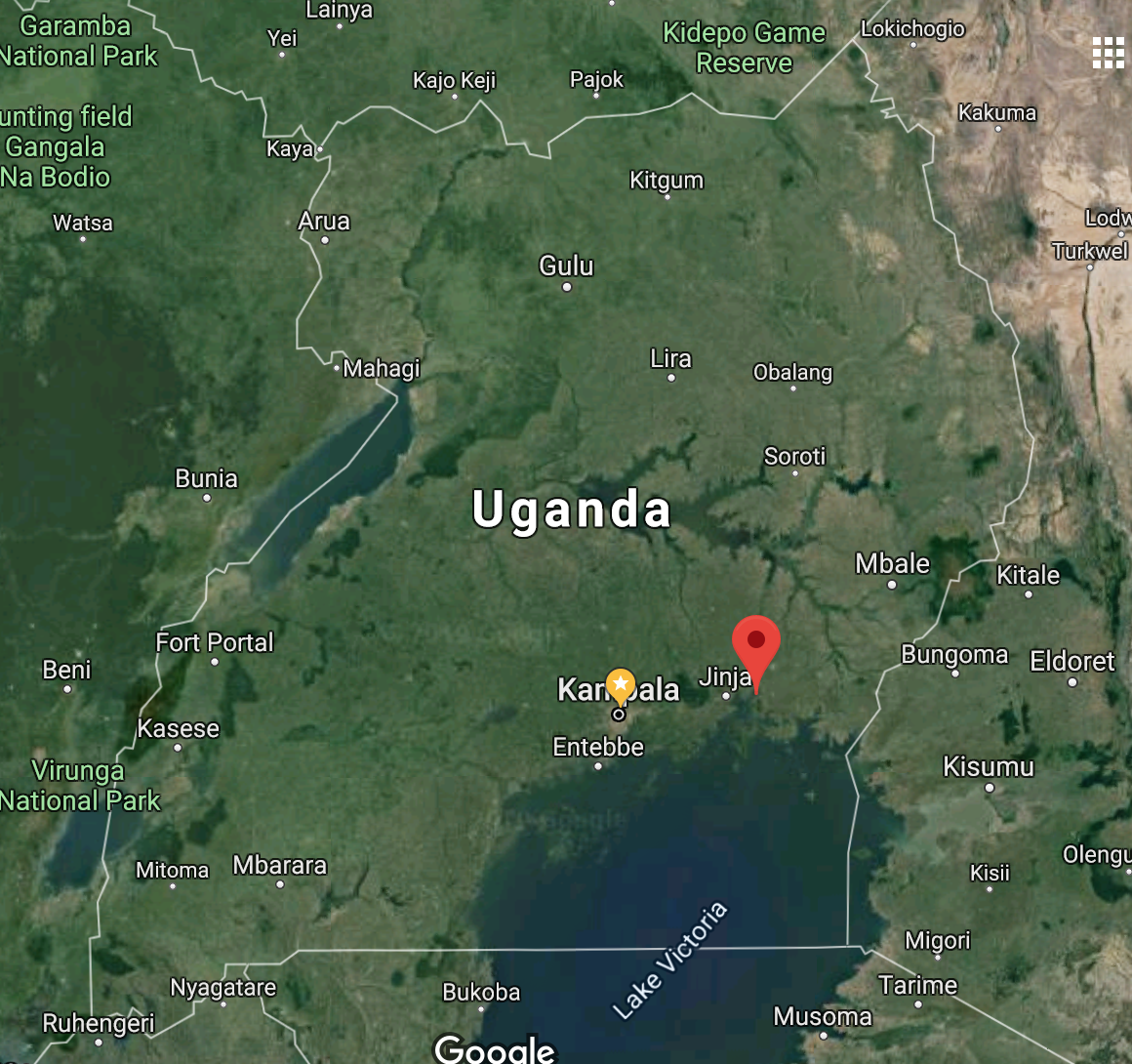

The 56-year-old fisherman first moved to the tiny remote village of Walumbe along the shores of Lake Victoria in 1984, searching for prime waters in which to fish for tilapia and other species.

He soon landed upon a better opportunity, discovering a huge expanse of seemingly unused land within a 9,000-hectare forest located deep in Mayuge District, Uganda. There, many other villagers were already planting small gardens among the trees, growing maize, cassava, potatoes and other crops to sustain their families and sell for small profits.

For decades, hundreds of people provided for themselves from these gardens and other resources obtained from the forest, including firewood, grazing land for their animals and sources of freshwater. But when the National Forestry Authority leased the land to Norway-based Busoga Forest Company in 1996 to plant pine and eucalyptus trees for timber export, these people, who had no official land titles, were forced from their gardens.

About 830 families were evicted from about 360 hectares of land that they used to farm, according to David Kureeba, a Program Officer at the National Association of Professional Environmentalists, which conducted a research and advocacy campaign about these forest communities.

Many of the people had migrated to the forest to work on a government beef farm and center to fight the parasitic sleeping sickness during former President Idi Amin’s regime in the 1970s. Others came escaping warfare in the north in 1987. When the current president Yoweri Muweveni came into power, the area was re-gazetted as a forest reserve, but “the gazettement was kind of informal,” Kureeba said.

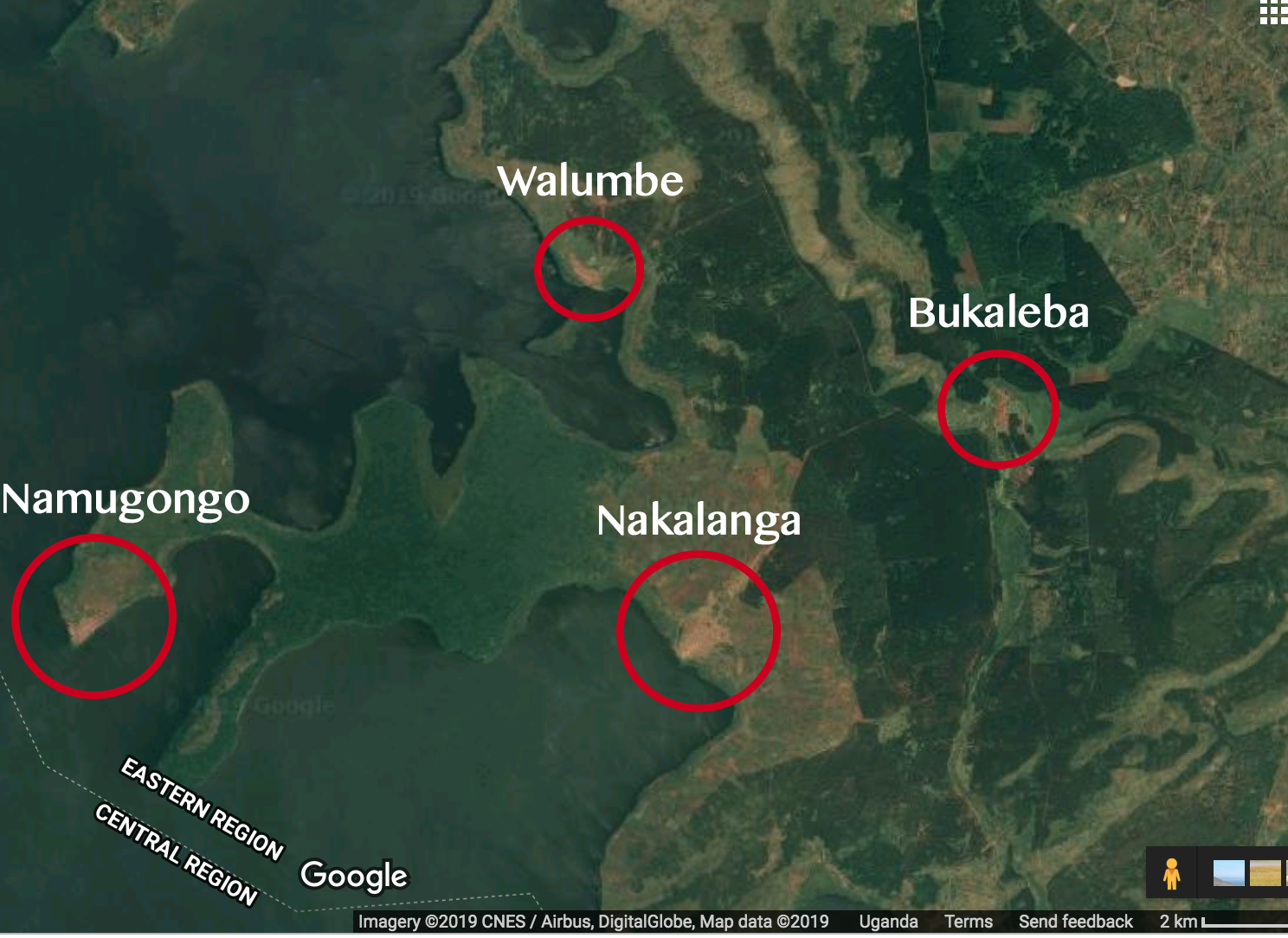

So the people remained, many claiming not to have been given terminal benefits after the government projects closed. Today, there are four communities making up a total population of about 7,500 people located within the reserve, three along the lakeshores and one within the forest.

Between 2002 and 2010, these villages grew by an average of 53 percent, according to a 2011 Ministry of Water and Environment report.

The National Forest Authority (NFA), the national body entrusted with managing forest reserves, contends that the area was gazetted as a reserve in 1948 and therefore these people are landless encroachers who “just forced themselves on the land which was not theirs,” according to Steven Galima, NFA Natural Forests Coordinator.

But complex land laws in Uganda do give some rights to people who settled on land 12 years before the 1995 Constitution came into place.

In April, the government through NFA and the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) began degazetting about 3,000 hectares of the 9,000-hectare Bukaleba Forest Reserve along with areas in the nearby South Busoga Forest Reserve, partly to find land to resettle dozens of villages that were evicted from the South Busoga area decades ago, Galima said.

The land currently occupied by the Bukaleba forest communities will be degazetted, as well as the 200-meter buffer zone alongside Lake Victoria that must be maintained to reduce pollution and conserve the environment of the lake, according to Stuart Maniranguha, the Kyoga Range Manager at NFA. Lake Victoria is the largest lake in Africa and shared by three countries that depend upon its resources, but pollution by the growing populations living near the lakeshores has severely polluted the water body and reduced its fish populations, a key economic resource.

But when NEMA completes the 200-meter demarcation within the next several months, the people living along the lakeshore will be made to leave their homes. According to Naomi Karekaho, NEMA corporate communications manager, whether they get compensation for the value of their lost land and crops or resettlement on degazetted land will be determined by the Office of the Prime Minister in time to come.

While National Forest Authority officials said the four villages that exist within Bukaleba are not likely to be among those resettled, the beneficiaries are still being identified, according to the Mayuge District Chairman, Hadji Omar Bongo, and the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development Public Relations Officer, Owbo Dennis.

Bongo also claimed that these forest communities will also be officially allocated a small portion of land within the degazetted area to sustain their livelihoods, a struggle that has been ongoing for eight years. Currently, the villages are fighting over a 500-hectare allotment that has been dominated by just one of the four communities.

Busoga Forest Company’s tree plantation is one of 6 large-scale forestry projects in Uganda with deals taking up a total of 47,339 hectares. Owned by companies from countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands and Norway, most of these concessions are monoculture plantations of non-native, fast growing tree species such as pine and eucalyptus that are cut and sold as timber in Uganda and abroad.

At the same time, many of the companies say they are fighting climate change through reforesting degraded lands and selling ‘carbon credits’ to polluting companies abroad. Investing in commercial forests is a national strategy to increase revenue and wood-based products to the Ugandan people, according to Galima from the NFA.

But while such projects are intended to inject economy and development into poor, low-resource areas, in many places, including Mayuge, their presence has often ended up depriving the most marginalized communities of their livelihoods without adequate efforts to replace them. People already living on the margins of society end up further ignored, and with even less.

One of these villages is Walumbe, population 1,500, a tiny landing site of grass-thatched houses nestled in a 200-meter buffer zone between Lake Victoria and the wall of perfectly spaced trees marking the Busoga Forestry Company plantation.

After their forest gardens were slashed, residents of Walumbe resorted to fishing to sustain their lives. But lacking enough money to invest in legal fishing gear such as nets that do not harm small fish, the fisherman say they are forced to use cheaper illegal nets and thus face the constant threat of arrest.

“Army men gather us when it comes to morning, from our houses, make us line up and beat us with sticks,” the fisherman Otewu said, revealing a series of long scars and wounds on his arms.

Without money for strong boats or lifejackets, the waters aren’t safe. This year, one fisherman was eaten by a crocodile. Residents first found his shoes, then his torso.

“You fish on the gunpoint now,” Otewu said.

Through the Trees: 25 Large-scale Foreign Land Investments Since 1990

Deep within the forest, a maze of seemingly endless rows of perfectly spaced trees stretch toward the horizon. Hugging each tree, in exactly the same place, is a small plastic bag, collecting sap. No other variety of plant or animal is evident amongst the sea of identical trunks. The uniformity is complete: In the late afternoon sunlight, even the trees’ shadows are the same length.

This is Year 23 of the monoculture tree plantation in Bukaleba Forest Reserve, Mayuge District: already the second crop of trees to be planted, en route for cutting.

In the midst of the silence, human life persists. Bukaleba village, population 800, is just a small collection of houses and buildings spread out along the major dirt road the runs through the forest. This is the former site of the government tsetse fly center and the first village to emerge in the forest.

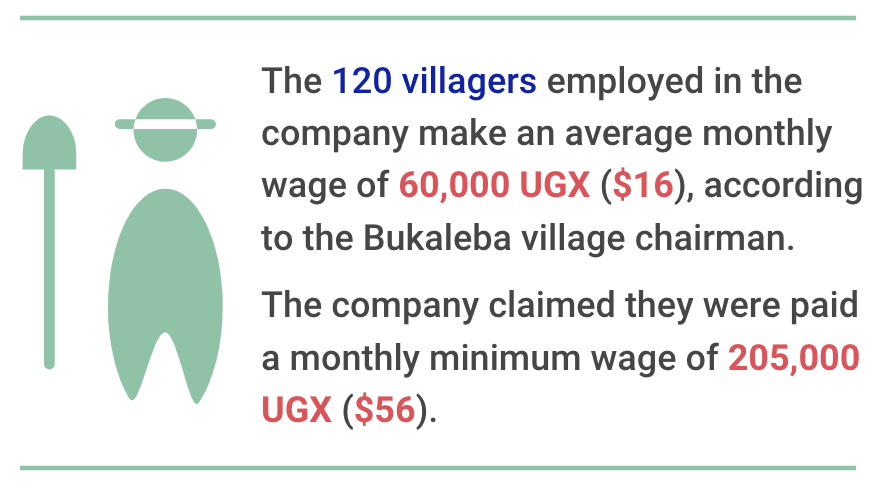

Today, without access to the community land or the lake, most villagers work casual labor jobs for the company. About 120 villagers are employed in the company as slashers, sprayers, and termite killers, the village chairman Aliphonse Ongom said. But in a month, he said the average employee makes only 60,000 Uganda shillings – about $16 – despite claims from BFC that they pay a monthly minimum wage of 205,000 Uganda shillings, according to the company’s 2016 Environment and Social Impact Report.

According to John Ferguson, the BFC Managing Director, the company employs about 1,000 Ugandans monthly, including 160 permanent staff, about 700 resin tappers, and about 300 contract workers in the field.

Ongom said his village also lacks good schools, with teachers who “come late and leave early” because “they are scared of the forest.” The closest hospital is about 11 kilometers away, so many pregnant women end up dying on the way, he said.

“So we are just like dead,” he said. “That’s why most of our children are remaining at home. They have nowhere to go. Because there is no way of making money here.”

In the 1990s, the Uganda government moved toward privatizing lands to attract foreign investment. The 1993 Tree Planting Act allowed timber investors to acquire land within forest reserves. Similar forestry acts were passed in 2001, 2003 and 2011.

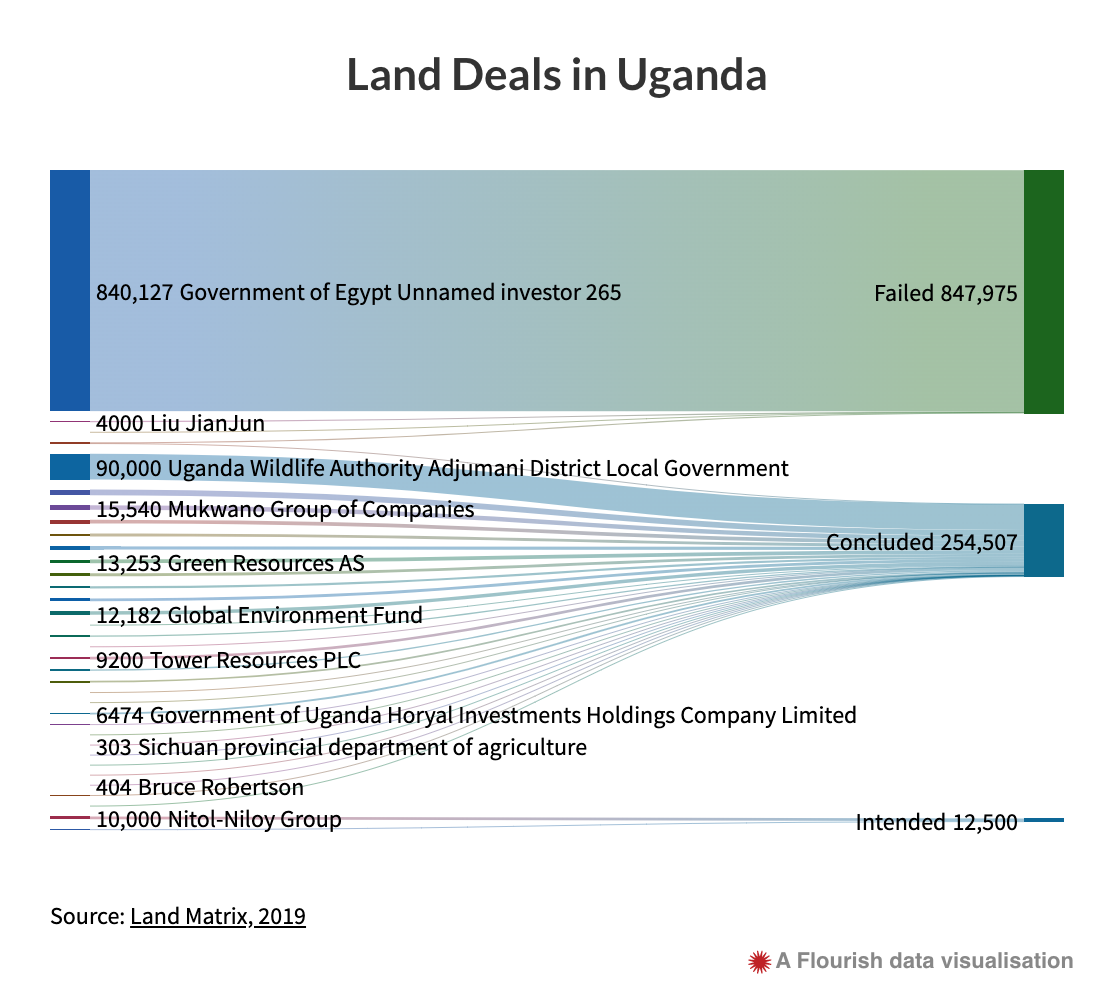

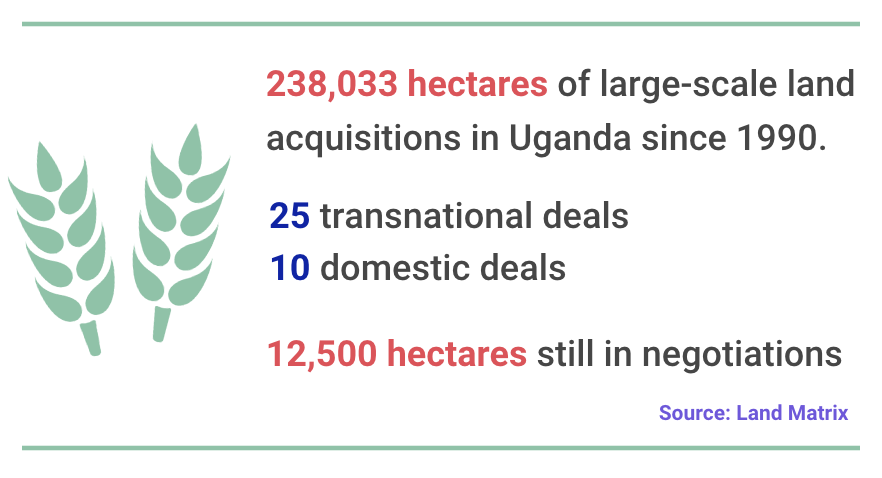

The Land Matrix has tracked 238,033 hectares of large-scale land acquisitions in Uganda since 1990, with most deals concluded since year 2007.

Most of this land was allocated to 25 transnational deals by investors from countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, Mauritius, Norway, and India. Twenty-seven deals are currently in production, including another 10 domestic deals by Ugandan companies or the government.

Investors from Bangladesh, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and India are also in negotiations for another 12,500 hectares of land mainly for export agriculture.

Busoga Forestry Company (BFC) obtained a 50-year lease of 10,054 hectares in Mayuge District in 1996, according to the Land Matrix. According to John Ferguson, the managing director of Busoga Forestry Company, the total area BFC plants in Mayuge is 6,300 hectares, and the remaining 2,700 hectares goes to conservation along with the 500 hectares for community activities.

Busoga Forestry Company is a subsidiary of Green Resources AS, a private Norwegian company established in 1995. Green Resources claims to be East Africa’s largest forest development and wood processing company, with 38,000 hectares of forest in Uganda, Mozambique, and Tanzania, a sawmill in Tanzania and electricity pole and charcoal plants in the three countries. The company manages 15 plantations, including two in Uganda, and in 2016 had net sales of $5,673 according to its 2016 Environment and Social Impact Report.

On its website, the company says it is one of the first companies in the world to benefit from carbon revenue from its forests. Under the international REDD+ scheme, carbon-emitting companies that contribute to climate change have an option to “offset” their negative emissions by buying “carbon credits” from tree-planting initiatives elsewhere in the world.

This year, BFC will sell about 325,000 tons of carbon, including 65,000 tons from Bukaleba, to the Swedish energy agencies under the United Nations advanced market operated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, according to Ferguson of BFC.

But time and time again, this model has proven too good to be true. In a 2018 study published in the Global Environmental Change journal, researchers at the IHE Delft Institute of Water Education in the Netherlands found that two participatory forest conservation projects in Ethiopia that supply carbon credits as part of the REDD+ scheme had ended up aggravating conflicts over the use of natural resources among the local communities.

Another 2018 study published in the Climate Policy journal found a “a gap between the REDD+ narratives at international level… and the livelihood interests of farming communities on the ground” within a forestry project in Indonesia.

The planting of monoculture alien tree species such as pine and eucalyptus also uses huge amounts of water and destroys the natural biodiversity of the environment, according to John Wanyu, a gastroeconomist scientist at Slow Food Uganda, an NGO that promotes the development of sustainable food communities.

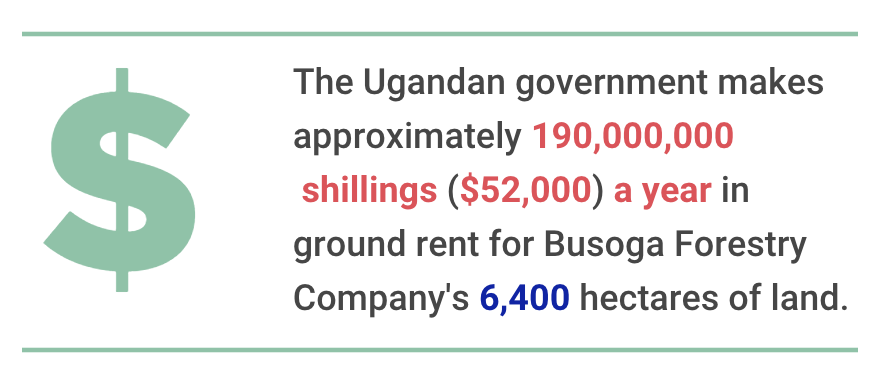

But the Ugandan government claims that investing in commercial forests is a lucrative venture for the developing country, which makes 30,000 shillings ($8) per hectare a year in ground rent – amounting to about 190 million shillings ($52,000) a year for Busoga Forestry Company’s 6,400 hectares.

Ferguson said his company contributes 2-3 million dollars a year to the Ugandan economy in taxes alone. He said 100% of the company’s products are now sold domestically, most to the national electricity supplier UMEME as electrical poles.

In 2016, eighty-six percent of BFC’s products in Uganda were sold domestically, according to Busoga Forestry Company’s 2016 Environment and Social Impact Report.

A Promised Land: 500 Hectares for the Community

When Busoga Forestry Company came in 1994, residents of Bukaleba village at first welcomed them, according to the Bukaleba chairman Ongom. Residents were initially permitted to continue to plant their crops among the trees in an agroforestry system known as ‘taungya.’ But the 2003 National Forestry and Tree Planting Act outlawed this practice.

“Before, we were making more money, because we were cultivating,” Ongom said. “People were getting around 30 or 40 sacs of maize, 3 or 4 million [shillings], so you can plan for your life with that money. But now, there is no way.”

According to Ferguson of BFC, the company’s lease agreement with the government stipulates that the company cannot allow any agroforestry, building of houses, grazing or other activity within its land because it is a national forest reserve.

In 2006, President Yoweri Museveni issued a press statement prohibiting eviction of encroachers in forest reserves and wetlands. Several years ago, the villages came together to protest at Parliament, asking for documents to allow them to legally stay in the area, said Makerni Steven, the NRM Chairman of Bukaleba Parish. After a series of conflicts escalating in 2011 when the communities cut down about 50 hectares of company trees, the president issued a directive mandating that the communities be given an area of 500 hectares to use to support their livelihoods.

Today, the villages lay claim to a 500-hectare area located around Nakalanga village where they are cultivating. But this village’s residents already use the entirety of the land for their farming, leaving no space to share it with people from the other three villages. A 2011 Ministry of Water and Environment report also confirms that this land was designated specifically to the Nakalanga community.

“That day they wanted again to divide the land, but the way they were handling it was not in a good way,” said Lilian Omoro, a 20-year resident of Nakalanga village. “Also, those people were from outside, so these people who were already here in the community, some of them they refused. So it brought some conflicts until they were stopped.”

Villagers also claim the space is too small to also provide grazing ground for cattle, so animal keepers frequently graze their animals in the forest. This has led to an increase in illegal grazing, Galima of the National Forest Authority said. Since around September of last year when the company started collecting sap from the trees, company workers started capturing cattle and requiring the villagers to pay 10,000 shillings ($2.7) per cow to get them back, Omoro said.

According to the National Forest Authority, the villagers are cultivating illegally in this area, which is intended solely for tree planting since it is within the forest reserve, said Aisha Alibhai, NFA Communications and Public Relations Manager.

She said that if the communities could organize to plant and sell their own trees, they would reap much more profit than relying on subsistence agriculture, while also gaining their own source of forest products that would further reduce the environmental burden.

But according to village leaders, not a single resident has taken up tree planting because they already have little land on which they said they must plant food to survive.

“We like food other than trees, even though trees are more profitable than food,” said Christopher Damba, former general secretary of Walumbe village. “You cannot convince someone that you plant trees and sell them and get food. How long are you going to go without food?”

Walumbe community, which has been kept out of the 500 hectares, has taken to cultivating within the 200-meter buffer zone along the lakeshore that is intended to be reserved for environmental conservation. In recent weeks, National Environment Management Authority officials came to demarcate the zone, telling residents that they must pay for permits if they want to continue to use the land for fishing, harvesting crafts or other activities. However, agriculture is not permitted, said Karekaho of NEMA.

The communities are currently pleading with the NFA Range Manager to be given management authority of this buffer zone to plant trees and cultivate, fearing that offering permits will attract big investors that will force them off the land, Damba of Walumbe village said.

The degazettement of the buffer zone is now 70 percent finished and should be completed by the end of the first quarter of the financial year, Bongo said, though Dennis of the Lands Ministry said the ministry is still waiting an official directive from Parliament.

National Forestry Authority officials said the biggest challenge in Bukaleba was “political interference.”

“Most of the big encroachers there are actually politicians in Mayuge District,” Galima said.

Community Development? 10% of Company Carbon Revenue Allocated to the Communities

On its website, Busoga Forest Company affirms its commitment to developing the communities affected by its projects and mitigating negative impacts of its presence such as loss of livelihoods.

Ten percent of company profits are intended to be used to develop the community.

“Green Resources’ strategy is based on the sustainable development of the areas in which it operates. The company believes that forestation is one of the most efficient ways of improving social and economic conditions for people in rural areas and aims to be the preferred employer and partner for local communities in these areas,” the company writes on its website.

In Bukaleba village, about 120 villagers are employed in the company as slashers, sprayers, and termite killers, the village chairman Aliphonse Ongom said. But in a month, the average employee makes only 60,000 Uganda shillings – about $16 – despite claims from BFC that they pay a monthly minimum wage of 205,000 Uganda shillings, according to the company’s 2016 Environment and Social Impact Report.

After conflicts with the local communities, BFC agreed to a ‘Collaborative Forest Management Programme’ in October 2011 that stipulated that 1.1 billion Uganda shillings (about $296,000) would be spent over the next five years to strengthen company-community relations and support the communities through various capacity building activities. Most of this money would come directly from the company, the agreement stated.

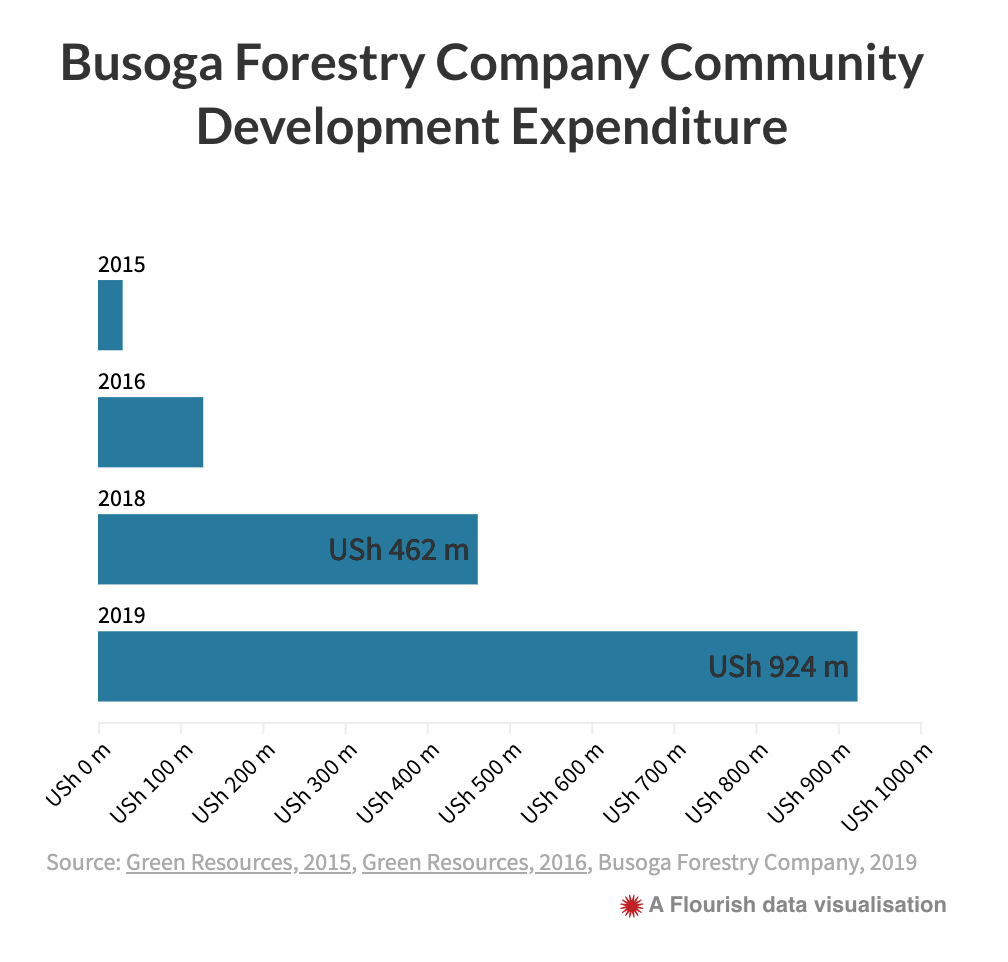

Dividing 1.1 billion Uganda shillings by five, it was expected that BFC would spend on average about 218 million shillings per year on community development. However, according to the publicly available Environment and Social Impact Reports released by BFC, the company spent only about 30 million shillings on community development in 2015 and 128 million shillings on the same in 2016.

According to the managing director of BFC, the company has been able to contribute more to community development since it finally became profitable in 2018. The company spent about $125,000 USD (about 462 million shillings) for community development in 2018, and this year it plans to spend about $250,000 (about 924 million shillings), Ferguson said.

The 2011 agreement also promised that BFC would contract plantation management to the local communities, hold skills trainings and mobilize resources for community income generation projects, and demarcate a community tree growing zone of about 30 meters from the line of the present settlements. The agreement also promised to move other settlements such as Bukaleba and Walumbe into the larger Nakalanga village.

But as of July 2019, none of the other settlements had been moved into Nakalanga, leaving them unable to access the 500-hectare community land located around Nakalanga. There was further no evidence or discussion of such a community tree growing zone around the four villages within the forest.

Ferguson of BFC said that the communities had been provided with seedlings, but while a 2018 Social Impact report provided by the company specified that 74,518 seedlings had been issued to community members in Kachung, there was no mention of Bukaleba.

According to Green Resources and BFC reports, some of the projects the company has undertaken to support the local communities include constructing three new water boreholes in 2018 in Bukaleba that benefited more than 3,000 people; providing medical supplies for two health centers with a monthly patient count of about 1,223 people, expanding a medical dispensary, maintaining more than 35 kilometers of community roads, sponsoring three girls to attend higher education, and increasing HIV/AIDS awareness with support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. BFC also implemented a multiyear improved cook stoves project that trained 256 people from 8 villages in 2016. Green Resources further permits community members to harvest small sticks from the forest to use as firewood.

But after training a group of Community-Based Organizations in the villages, the company left without providing the promised startup capital except to a single group, said the village chairman Ongom.

Villagers further maintained that losing the land where they grew food to survive was still the source of almost all their problems and one that has never been adequately addressed by the company or the government. The government, however, states that they never had rights to the land.

According to Ferguson of BFC, the company has increased food security for more than 1,823 households in its two forest reserves in 2018 through distributing cassava cuttings and groundnut seeds. In the entire history of the project, the company has helped ensure food security for more than 12,761 people, according to a report compiled by Kizza Simon, the company’s 8-year ESG Manager.

Ferguson said the company had nothing to do with any history of communities being forced off their lands. When BFC came in in 1996, nobody was on the land, and since then, the company has invested a large amount of resources to support the neighboring communities, he said.

“We don’t own the land. When they talk about people being moved, we’ve never done it; it wasn't our company that did it,” he said. “NFA put out a tender for people to operate on these plantations. We applied for that tender and we were successful based on our plan for what we would do. We moved onto land that required to be planted; there weren’t people there when we moved onto it, and the history behind it is something that NFA would be able to give a lot more insight than we can.”

A 2014 report based on more than 150 interviews by the Oakland Institute, a U.S.-based environmental think tank, found that more than 8,000 people in Bukaleba and Kachung Forest Reserves had faced “profound disruptions to their livelihoods” due to the presence of Busoga Forestry Company, including forced and violent evictions, the denial of access to land that sustained them to grow food and graze cattle, and the lack of access to forest resources.

The authors termed the situation in Bukaleba a form of ‘carbon violence’ to explain how subsistence farmers and poor communities have borne the brunt of costs related to expanding forestry plantations and global carbon markets in Uganda.

Alibhai of the National Forest Authority said the communities need to “seek help” by officially writing to the NFA to be recognized as a formal Community Forest Management group, after which NFA can support them such as by giving them trainings in tree nursery management, among other benefits.

According to Ferguson of BFC, while forestry projects have often been condemned as the “smelly family member,” the sugarcane plantations such as Kakira Sugar Works that own more than 50,000 hectares near BFC’s operations in Mayuge actually take in 15-20 times more water than trees while leaching land that used to be used to grow food crops.

“The perception of forestry around the world is that they’re seen as the bad boys for some reasons, maybe because trees are big beautiful things and how can you cut them down and yes those are the realities,” Ferguson said. “But if you look at how sugarcane is taking out the business of the gardens and where people are growing their crops, you see it’s getting dryer and dryer every year.”

Plantation Deals: British, German and Norwegian Companies Invest in Ugandan Forests

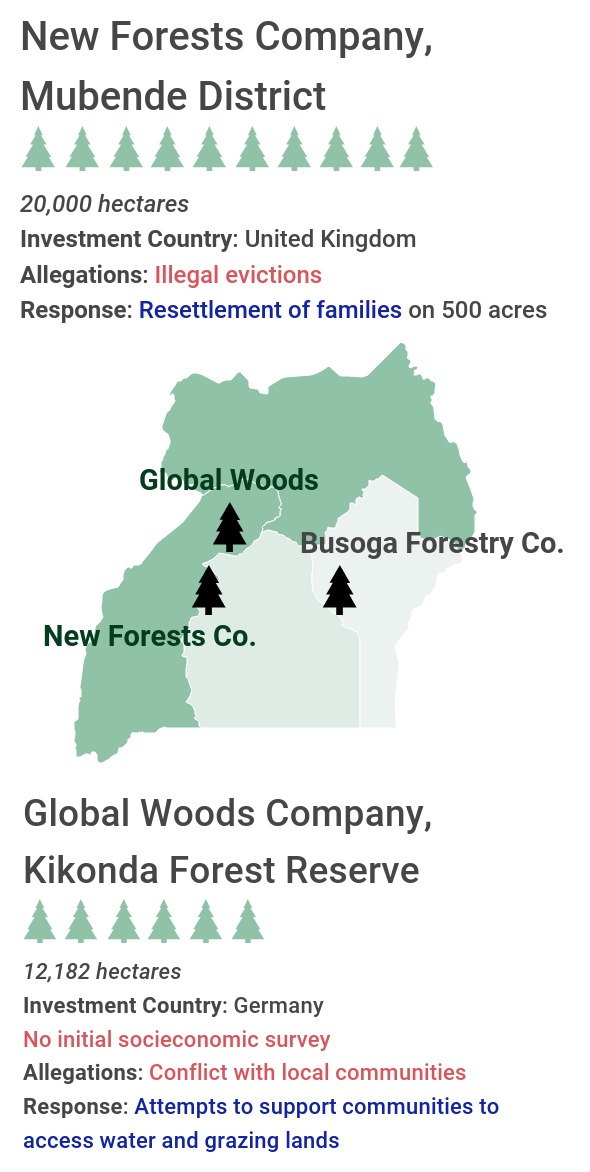

In Uganda, 3 of the top 4 transnational deals making up a total of 42,236 hectares are in forests, with companies from the United Kingdom, Germany and Norway investing in monoculture timber plantations located on government-run forest reserves.

Like the Mayuge deal, these other deals have been rife with controversies.

In 2004, the UK-owned New Forests Company invested in 20,000 hectares of forest land in Mubende District to develop three timber plantations that would also be used for carbon offsetting. But in 2012, the company was closed after allegations by Oxfam that the company had illegally evicted 20,000 people from the land.

After a yearlong mediation process by the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank Group, the company restarted operations again in 2013. A community cooperative worked with the company to purchase 500 acres of land within the forest to resettle families and start agricultural projects.

In 2002, the Uganda National Forestry Authority leased 12,182 hectares of land within the Kikonda Forest Reserve near Hoima in western Uganda to the German-based Global Woods company for 50 years.

Eight thousand hectares of this land are currently planted with pine and eucalyptus trees for local and international export. The project is also generating income from selling carbon credits. But the company has also encountered conflict with the local communities: People living around the reserve complained that they were arrested when they or their cattle entered the area to access water sources, denied access to community water tanks, and imposed upon with fines and corruption by forest rangers, according to a 2013 report by the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation and a 2015 report by the World Rainforest Movement.

The researcher found that the problems came partially because Global Woods did not take time to understand the local communities and how the tree planting project would affect them. Global Woods only conducted an initial socio-economic baseline survey in 2011, 9 years after the project had already launched.

In 2016, Gold Standard required Global Woods to provide remediation for any corrupt infractions, train local staff, and help resolve any land title disputes. In response, Global Woods began constructing valley dams for cattle owners to access water and relaxed its ban on grazing to solely the newly planted areas. Company Facebook posts in the past several years indicate projects to install local water boreholes and lead skills trainings for cattle keepers and farmers.

Isolation: Without Roads, Remote Communities Suffer

Joseph Kivumbi Kizza stood at the edge of his village, before a long dusty trail that stretched toward the forest, into the horizon.

This is Namugongo village, a remote community at the end of a peninsula of wetlands that can only be accessed by a 45-minute journey on motorboat from the Walumbe village landing site.

The major issue for the people of Namugongo is the lack of a road connecting them to the mainland, where they could easily travel to nearby towns and the Kenya border. As of now, their only access to the outside world is by boat or a three-hour walk on the informal path that now runs across the peninsula.

They slashed this small path by foot, but when they wanted to widen it into a road, NFA told them they would injure the forest, said Joseph Kivumbi Kizza, the Namugongo chairman.

But it hinders their access to markets, good schools and health centers.

The Walumbe landing site also struggles due to its isolation. There are no public buses that cross the forest reserve, so residents must take motorbikes to reach the nearest health center – a journey that many often cannot afford.

For Christopher Damba, this isolation contributed to worst tragedy of his life. His daughter of 5 years old, a tiny smiling ball of energy during my visits from March to May, died in June while the family was transporting her to see a doctor. She was Damba’s second child to pass away.

“She just felt hot body one day and the second day we were on the way to hospital and she died on the way,” Damba said.

But the people in Walumbe continue on. For more than 20 years, now-68-year-old Joyce Nankwanga said she and her husband were cultivating 6 acres of land in the forest. “Nobody told us we couldn’t be there until the company came,” she said. But after they were chased away, Nankwanga’s husband died from cancer, and she was left to struggle to provide for four children solely through daily sales of a local cassava breakfast meal called ‘katogo.’

Nankwanga entered her small house, pointing to the uneven dirt floor where the family sleeps, eats, cooks and lives, the elderly woman said.

“It was a simple life, now gone to hard life,” Nankwanga said. “I have no hopes or dreams… I have just given my life to God.”

*Visualizations by Code for Africa.