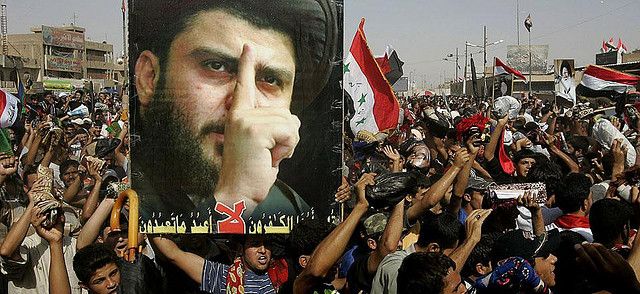

Tens of thousands of followers of influential Shiite cleric Moktada al-Sadr flooded the streets of Baghdad, Najaf, and Basra last week for some of the largest public rallies in several years. At one point, they might have been demonstrating—even fighting—against the United States as part of the Sadr-led uprising that made the young man’s name. But these protests weren’t about the U.S. presence. Instead, they focused on a different target: the government of Iraq itself.

After four years of exile in Iran, Sadr has reinvented himself. He has lost none of his anti-American fervor (his political party recently suspended a pair lawmakers merely rumored to have met with American officials), but the Sadr Front—one of the largest members of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki’s fragile coalition—has surprised many Western and local observers by emerging as a leading critic of the Iraqi government. Its parliamentarians investigate contracts on a line-by-line basis, audit the government’s performance on power generation, and demand that Maliki create the jobs his party promised—hammering the relevant ministers in ways never seen before here. In doing so, they are following a model pioneered by Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza. If their popularity keeps rising, they may have found a way for Islamism to take hold in a broadly secular country.

At Sadr’s Baghdad protest, some of the 25,000 in attendance carried broken fans, air conditioners, and generators to signal inadequate electricity—a problem on which the United States and Iraq have spent $7 billion since 2003. They carried empty caskets to dramatize Maliki’s failure to create jobs or increase the food rations on which many poor Shia families depend. And the crowd cheered as Sadr Front politicians berated the Iraqi government. “We want services, jobs, and a portion of the oil revenue,” Ibrahim al-Jabiri, a Shiite cleric and political adviser to Sadr, said during the rally. The crowds chanted back, “Now, now, now!”

The oversight hearings, meanwhile, are making for Iraqi-style must-see TV. The parliamentary commission investigating $1.7 billion in fraudulent Electricity Ministry contracts is run by Sadrist Uday Awad. Last month, Awad summoned Raad Shallal (the former minister who inked the deals and then resigned in disgrace) and Hussein al-Shahristani (a deputy prime minister and close Maliki ally) to appear before his panel. Awad and other Sadrists accused the two men of negligence and incompetence.

Shahristani insisted that he wasn’t involved in the deals and shouldn’t be held accountable, but Awad held up internal documents the committee had gathered that showed Shahristani knew about and supported them. Western officials here said they were impressed by the tenacity of Awad’s investigation: One firm that won a contract doesn’t appear to exist, and the other was already bankrupt when the agreement was signed. “This government is failing to provide what our people need and deserve,” Jawad al-Shihaily, a Sadrist lawmaker, said in an interview. “We will hold them accountable until they do.”

Americans are ambivalent about the evolving Sadrist movement. On one hand, it appears to support democratic values such as reform and transparency. On the other, it echoes moves by other armed Islamist groups in the region—especially Hezbollah and Hamas, both of which now carry out fewer attacks and instead focus on participating in government. Like the leaders of those groups, Sadr takes a populist line on corruption, advocating good-government reforms and appointing technocratic lawmakers and ministers. It has given his movement a more moderate, nonsectarian sheen. “It is becoming much more similar to the Lebanese Hezbollah model,” Maj. Gen. Jeffrey Buchanan, the top U.S. military spokesman here, said in an interview.

Some American officials fear the model augurs poorly for Iraq. Hezbollah lawmakers brought down Beirut’s government earlier this year; they then forced the appointment of a prime minister tied to their party and unfriendly to Washington. Meanwhile, the group has refused to disband its private militia. Its fighters have acquired new weapons from Iran and threaten new attacks against Israel.

Sadr could easily follow suit, using his political power to bring down the Maliki government; he could then force the appointment of a more religious or pro-Iranian premier while keeping his troops at the ready in case his demands aren’t met. So far, those demands haven’t included the adoption of sharia, but for now Sadr is still accumulating power. He hasn’t disbanded his militia or put them under the control of Iraq’s central government, raising the specter of renewed political violence after the U.S. withdrawal.

At the moment, Sadr appears to be keeping his options open. In a recent statement, the cleric urged his followers to “halt military operations” until the end of the year to give the U.S. time to withdraw its forces. But he warned that if the withdrawal was delayed for any reason, “The military operations will be resumed in a new and tougher way.” Since rising to prominence in 2003, Sadr has wavered between warrior and politician. His movement’s new direction means he may never have to choose.