We’re letting millions of gallons of sewage-contaminated Tijuana River water go to waste by tossing it to the Pacific Ocean.

That’s the opinion of two competing forces — one from the United States and another from Mexico — that are rethinking the region’s oldest and dirtiest problem, imagining it instead as a moneymaking opportunity.

“Why would you throw it away when you can sell it?” said Kurt Tetzlaff, president of WinWerks, a San Diego-based company that pitched a Tijuana River wastewater recycling project this month to the International Boundary and Water Commission, an international agency that executes border- and water-related treaties between the U.S. and Mexico.

The commission operates a treatment plant in the South Bay that’s supposed to catch and clean effluent from the Tijuana River as it spills over the border. Without fail, heavy rains hitting the Mexico side wash way more water and sewage into the river than the South Bay plant was built to handle.

That’s where WinWerks comes in. Tetzlaff proposed capturing that water, treating and reselling it to Southern California utilities, which are desperate for more local supplies.

Southern California doesn’t have enough freshwater sources to begin with. Instead we pump it in from the Colorado River and Sierra Nevadas at high prices. As climate change makes those sources more unreliable, municipalities like the city of San Diego are trying to develop their own resources by repurposing wastewater. San Diego plans to spend $3.5 billion on a project to reuse its own sewage, called Pure Water, which is supposed to provide a third of the municipality’s drinking water needs by 2035.

Why couldn’t we do the same with the Tijuana River, Tetzlaff said.

WinWerks would build an additional set of treatment facilities on an underused piece of property right next to the South Bay plant. Then, using a century-old science called electrocoagulation, treat what water we otherwise dump in the ocean.

Electrocoagulation is a process that shocks pathogens out of water using small amounts of electricity, which separates gross stuff from the pure water molecule. Added microalgae can gobble up the fats and oils, and fine filters sift out the other bad junk.

“We can make the water as clean as they want it to be, up to drinking water standards,” Tetzlaff said.

The process could wipe out many of the contaminants discovered in the watershed during a joint water quality study between U.S. and Mexican water agencies, Tetzlaff said. That includes heavy metals, radioactive materials, coliforms and phosphates.

A March study by the World Bank shows 80 percent of the world’s wastewater is released into the environment without proper treatment. Utilities in other countries are cutting operation costs already by reusing gas or biosolids generated by wastewater. But Tetzlaff’s company wants to own the water and sell it.

Tetzlaff hopes to forge a public-private partnership with a government agency working on the problem and perhaps a piece of the $300 million the Trump administration gave the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to fix the Tijuana River sewage problem. On Friday, the EPA will update the public on its process to engineer a solution.

“What we’re suggesting EPA has by no means agreed or disagreed to,” Tetzlaff said.

Tetzlaff wagers there’s tens of millions to be made repurposing that sewage. But the cost of electrocoagulation and his facilities, he says, would be cheaper than building an entirely new, brick and mortar treatment plant to add capacity to the South Bay plant.

Electrocoagulation could add 25 to 60 million gallons a day of cleaner water to the region’s needs, he estimated.

Everyone in Southern California is worried about securing more locally controlled water supplies. Right now San Diego County has to pay the L.A.-based Metropolitan Water District for Colorado River water, the main source of water for the San Diego region. Instead, some San Diego water managers want to build their own $5 billion pipeline to the Colorado River — but that plan wouldn’t bring a drop more in supply to the region.

“Our initial numbers show that it would be cheaper than the current cost … of getting drinking water from the Colorado River,” Tetzlaff said.

A Mexican Solution?

But there’s another player on the Mexican side of the border with its sights set on that sewage.

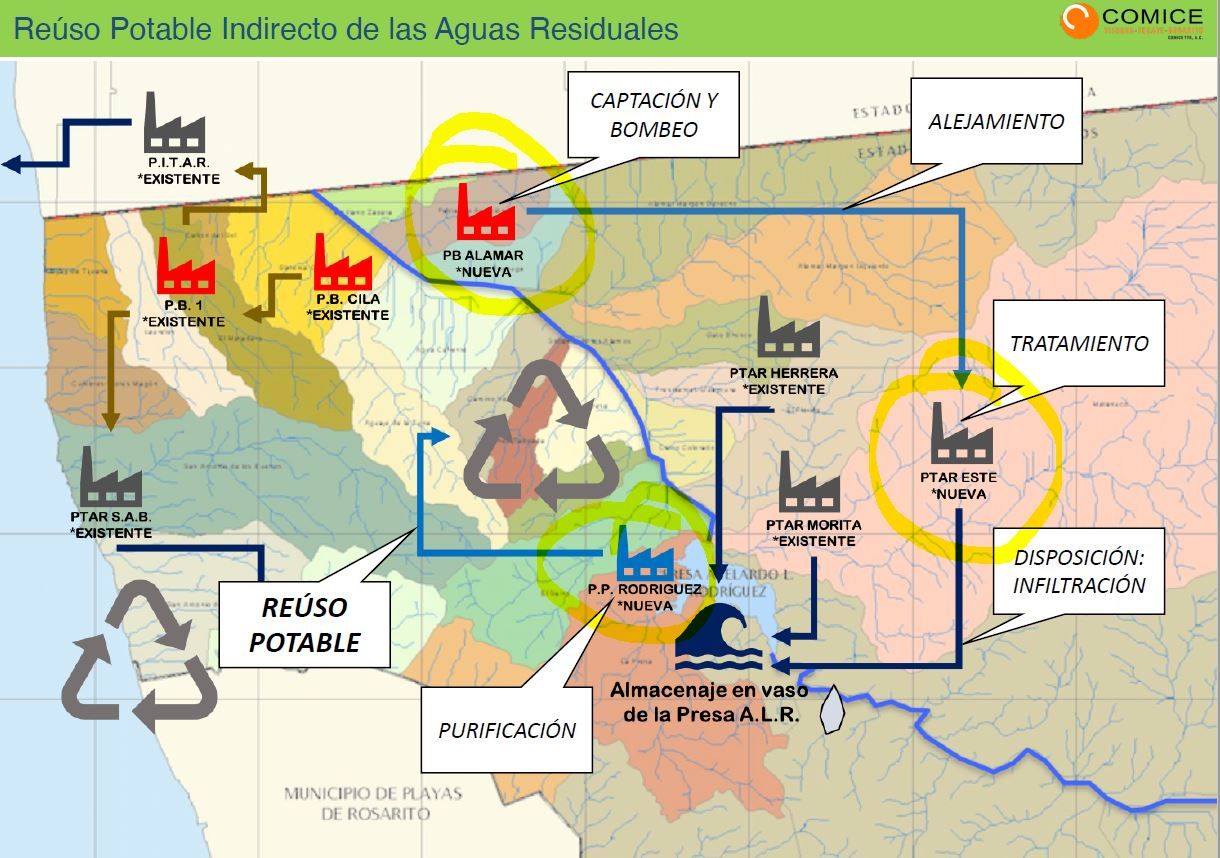

Comice, a Tijuana-based conglomerate of engineers, contractors and business experts, also proposed a water-recycling project to the International Boundary and Water Commission. Their plan would add a wastewater purification plant to the Tijuana network further down the watershed on the Mexican side.

According to Comice’s presentation to the International Boundary and Water Commission on Oct. 27, a new pump station could be built near the border around the Libertad neighborhood to capture excess flows from Tijuana. It would pump the runoff to a new treatment plant on the eastern outskirts of Tijuana and then to a purification plant near the Presa Abelardo L. Rodriguez, a dam and reservoir south of the city and much further upriver.

The plan means excess water would be rerouted before it even crosses the border into the United States. That’s less flow sweeping through concrete canals, carrying garbage and other undesirables to plague the beaches of Southern California.

Ruben Garcia Fons, a Comice member with decades of experience in the Tijuana wastewater engineering world, wagers the suite of three plants would cost less than building just one in the United States. For instance, it cost over $250 million to build the South Bay plant almost two decades ago.

Garcia Fons estimates the whole project would cost $80 million and capture 80 percent of the undesirable water before it reaches the border.

“What we’re proposing in Tijuana is cheaper, more certain and solves the water problem,” Garcia Fons said.

There’s one caveat. Though the Comice project stands to make money by producing jobs, water cannot be bought and sold in Mexico like it can on the U.S. side.

Under Mexican law, the federal government owns the rights to water on behalf of the public. Some changes to that law in the 1990s allowed the government to make concessions, or grant private parties’ rights to provide water services, said Margaret Wilder, associate professor of geography and political ecology at the University of Arizona.

But “under privatization, water fees become sky high and, in most cases, has failed (in Mexico),” Wilder said.

Garcia Fons agrees.

“In our experience, (privatization) it’s not a transparent business,” he said.

The spirit of Mexico’s water laws mean proposals like Comice’s can’t promise the same kind of private financing WinWerks can. Instead, the Mexican government would likely need to step up and support it in some way.

But while private contractors on the U.S. side are hungrily eying the EPA’s $300 million budget to build a sewage solution here, the EPA could still choose to help pay for a project on the Mexican side.

Garcia Fons views the sewage problem as a public health concern more than a business one. He doesn’t want to hand down contamination to his children and grandchildren, Garcia Fons said. But it’s clear there may be a battle ahead over brown water.

“This water is Mexican, albeit dirty and contaminated,” Garcia Fons said. “It has an immense value. And we have to fight for every drop.”

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center and The Water Desk at the University of Colorado Boulder. Vicente Calderon of the Tijuana Press contributed to this story.