CÚCUTA, Colombia—Once a month, Marisol Ramírez travels 43 miles by car and then on foot to cross one of the most dangerous borders in the world. She joins the estimated 30,000 people daily who travel across the Simón Bolívar International Bridge to enter Colombia from Venezuela. As the economic and political crisis in Venezuela has intensified over the past few years, this bridge has become one of the main ways to access affordable food and goods for thousands of Venezuelans.

Like many with chronic health conditions, Ramírez knows her health depends on reaching Colombia.

“If during the bridge crossing, they don’t even give us the chance of at least getting to the hospital, we are going to go die,” she said in an interview over the summer.

Ramírez, 56, has lived the past 20 years of her life with HIV/AIDS. Until recently, she had been able to get treatment to keep the virus in check in her home in Cordero, Venezuela, where she would receive antiretroviral therapy that helps control the number of copies of the virus in her body. She was doing fine with her medication until the health care system of Venezuela stopped purchasing the medicine she needs.

“Almost eight months ago I changed [where I receive antiretroviral] therapy, because since 2017 in Venezuela, they stopped buying [antiretroviral] drugs,” Ramírez said. “What little has arrived are from donations, because the government hasn’t [been] buying the treatment.”

Venezuela’s health care system is collapsing—another victim of the nation’s economic and political turmoil. In 1998, Hugo Chávez was elected president promising that he would provide free health care to all Venezuelans. But the oil-rich country’s economy has struggled since global oil prices began to fall in 2008. Since current President Nicolás Maduro, a protege of the late Chávez, came to power in 2013, the situation has gone from bad to worse. Under Maduro, government corruption has flourished, and runaway hyperinflation of the Venezuelan currency has made the Venezuelan bolívar nearly worthless. As a result, the country’s medical system is severely under-resourced. Government funding for medical care has been slashed, more than half the country’s doctors have fled Venezuela, and drastic shortages in medical equipment have hampered the ability of hospitals to provide even basic treatment for their patients.

Conditions have severely worsened since the economic and political crisis in 2017. According to a report by Human Rights Watch, the infant mortality rate in Venezuela nearly doubled from 2012 to 2017. The report also found that vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles and diphtheria, which had once been eliminated in the country, are now frighteningly on the rise.

Venezuela is also the only country in the world where large numbers of HIV patients have been forced to discontinue treatment for lack of antiretroviral medication, Human Rights Watch reports. As of 2018, 15 of the 25 antiretroviral drugs procured by the government were completely out of stock in Venezuela. For patients like Ramírez , the only option is to go outside of the country for treatment.

The trip to the border city of Cúcuta is not easy—increasingly, shortages of gasoline and the dangers of crossing the border have added obstacles to the journey. The Simón Bolívar International Bridge is packed all day with people coming and going, carrying large packages of food, drinks, household supplies, and materials back with them to Venezuela. The climate is sweltering hot and humid, much hotter than Ramírez is accustomed to.

Buying gasoline to drive to Cúcuta from Cordero or paying the price of a bus ticket were once affordable, but due to the hyperinflation of Venezuela’s currency, it is increasingly expensive to make the journey. And the crisis may be getting worse before it gets better.

“Just last month, they gave me enough [anti-retroviral drugs] for three months, because due to the situation in the country, we can’t be going up and down to get here. The price of [bus] tickets are incredibly high, and we can’t be coming down here every month,” Ramírez said.

Antiretroviral therapy is recommended for everyone who has HIV. It can reduce the number of HIV viruses to undetectable amounts. Reducing the amount of the HIV virus not only helps people live longer and improves their health, but it also reduces the risk of transmitting the virus to others.

When treatment options disappeared in Venezuela, Ramírez found a nongovernmental organization that could help her receive the treatment she needs. But that NGO only has an office in Cúcuta, on the Colombian side of the border.

Ramírez began crossing the border monthly so that she would never have a break in receiving treatment for her HIV, but the trip is exhausting for her. It is also one of many ways her life has been complicated by the Venezuelan crisis.

Ramírez is also caring for her mother, who has cancer. Her mother should be receiving chemotherapy, but that is another treatment widely unavailable in Venezuelan hospitals. Ramírez must provide everything her mother will need if she takes her to the public hospital in her hometown. Patients in Venezuela have to bring all their own supplies to hospitals in order to receive treatment, including buying their own water, gloves, and syringes.

“It’s a bad situation for many, because if we have enough to eat, we don’t have enough to come here to get medication, and if we come and get medication, we don’t have enough to eat,” Ramírez said.

Even the most basic things like vitamins are hard to access in her country.

“A lot of time, my friends get sent vitamins from the U.S., and they share with me,” she said. “Otherwise, we couldn’t take them, because medication is too expensive.”

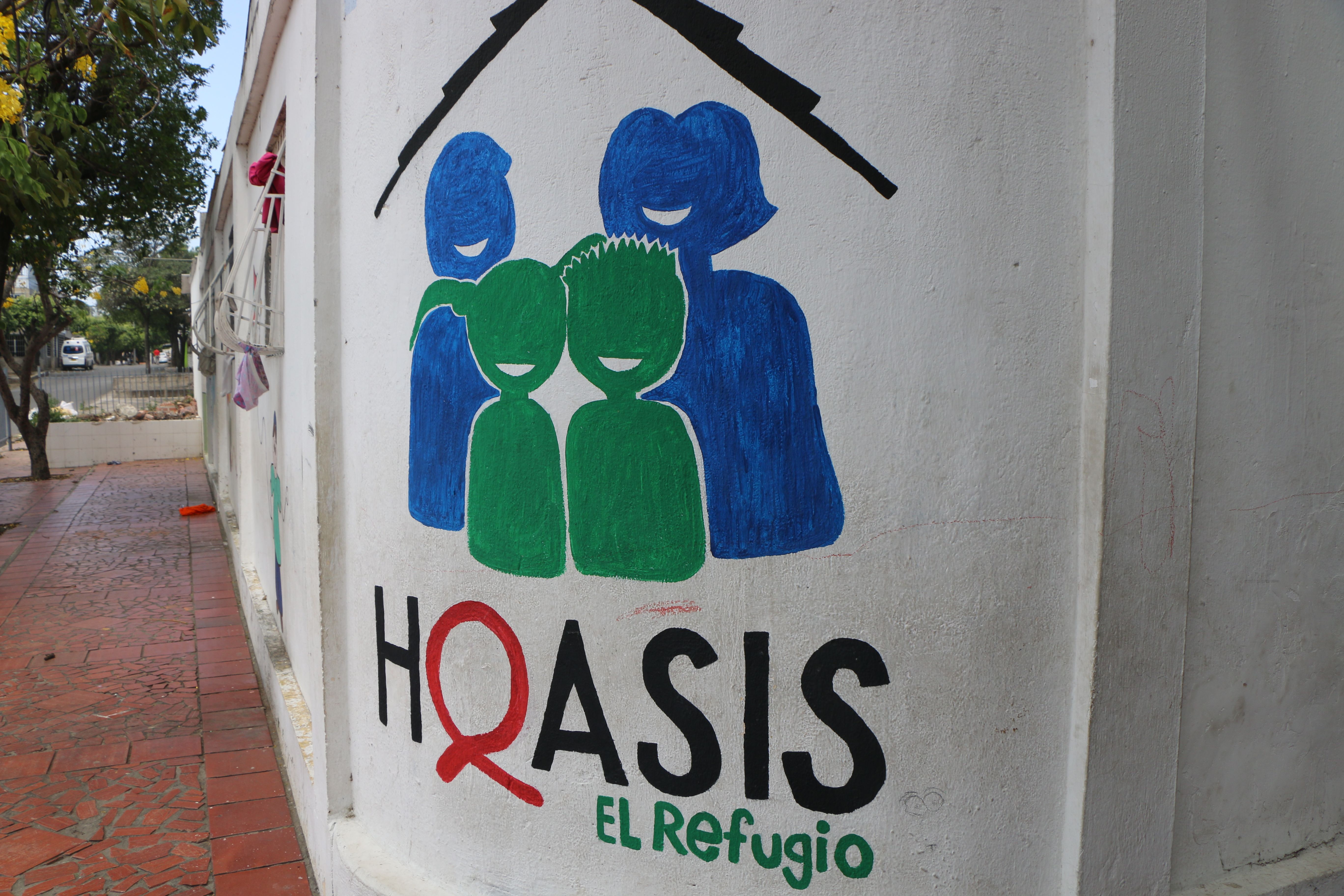

Just a few miles away, on the other side of the city of Cúcuta, Pedro González Díaz looks through the bars of a metal fence at Fundación Hoasis, a shelter that he’s come to call home. He has lived in the shelter for over a year now. In Venezuela, González Díaz had a family, a house, and a 15-year career as a police officer. Now he is a refugee here in Colombia.

“Suddenly I was left with basically nothing. Quitting after 15 years of work, leaving my sister, my dad, my home. … It was hard,” he said.

González Díaz lives with HIV/AIDS as well. When he arrived in Colombia, his health was failing. Coming from a different part of Venezuela than Ramírez, who lives relatively close to the border, he had been unable to access retroviral therapy in Venezuela for two years. His viral count was high, and he was badly ill.

As a police officer, González Díaz had never disclosed that he was living with HIV/AIDS, fearing that he would face the stigma many have toward those with the disease. When he left, he was charged with treason for abandoning his country. Nevertheless, he had nowhere to turn for medicine inside Venezuela. In the end, he fled to Colombia looking for any kind of help.

“I thought [about] Bogotá, since it was the capital, the biggest city, I thought they could help me there,” González Díaz said. “But it was the opposite—they sent me back to Cúcuta.”

Cúcuta has become the center for NGOs working on the Venezuelan crisis. Although Venezuelans have migrated throughout Colombia, González Díaz found his only option was to return to the border city.

González Díaz arrived in Colombia without a work permit. He also cannot receive treatment from Colombia’s public hospitals without a work permit or a special permission called Salvoconducto, which allows some Venezuelans in Colombia to access health care for children and to enroll in public schools. However, he can receive help from an NGO that works specifically with Venezuelans living with HIV.

González Díaz now receives monthly treatment from the same NGO where Ramírez receives her medicine, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation. Upon returning to Cúcuta, he ended up in the shelter run by Fundación Hoasis, where he stayed during his recovery. When he arrived, he was very ill.

“Some people come here with one or two years without having taken [antiretroviral drugs]. So they arrive already in critical states. The virus has wrought disasters like that,” said Ricardo Villamizar, the head of Fundación Hoasis. The foundation provides both shelter and accompaniment for residents when they go to receive their treatment.

“Being here, in part I am happy, because I came with a purpose, and that was my treatment,” González Díaz said. “But in another way, I’m a little sad, and it’s because I’m not working. It’s difficult because of my health … if I get sick … it’s something I’m afraid of.”

While his health has improved since starting to receive treatment again, González Díaz found himself caught in legal limbo and confined to Fundación Hoasis. He cannot receive treatment in a public hospital unless his condition is deemed an emergency. He is also afraid that he could be deported by Colombian police, since he does not have the proper documentation to stay in the country.

Because González Díaz was charged with abandoning his country, he and Villamizar believe he would be arrested if he were to go back to Venezuela. It is a possibility he does his best to avoid.

“Whenever I have a consult or appointment, I have to pay for a taxi,” González Díaz said. “[Otherwise] I fear that immigration will grab me and throw me back into Venezuela.”

“Right now, Pedro is sick and he needs medical attention and he cannot get it,” Villamizar. “He can’t leave because he is illegal. He doesn’t have a permit of permanence. His passport expired, and he cannot renew the passport, because as soon as he crosses the bridge they would capture him.”

Other than going out for his monthly treatment, González Díaz stays inside the walls of Fundación Hoasis. He has not been able to see his family in over a year.

Fundación Hoasis occupies two buildings with a handful of beds in the outskirts of Cúcuta. The foundation works with Venezuelans and Colombians alike, although in recent years its focus has increasingly shifted to serving the Venezuelan population in Cúcuta. It operates without support from the government and mostly relies on donations from friends and neighbors. There have always been many with HIV here, but the need is growing.

“Before, we would attend to 75 or 80 people in the two houses,” Villamizar said. “Now it is 130 or 150.”

To date, about 7,700 Venezuelans living with HIV/AIDS have left the country in order to seek treatment elsewhere.

While the Venezuelan government has acknowledged that there are medical shortages, political leaders have maintained that the country is not experiencing any humanitarian crisis and that it guarantees its citizens access to basic medicines. There are few signs that they will take serious action to address these shortages anytime soon.

Ramírez helps run a civic organization that tries to advocate for those in the region around Cordero who have the disease. She is most concerned about what the situation will mean for newborns and children in her community.

The risks of going without HIV medication are heightened for mothers. Even if they get through a pregnancy without transmitting the virus to their child, Ramírez explained, concerns endure that “she starts breastfeeding and that’s when the HIV explodes, and the baby is infected.”

The economic and political crisis in Venezuela has shown no signs of slowing. As of 2016, the last year Venezuela released data from its HIV/AIDS program, 90 percent of HIV patients registered for antiretroviral treatment in Venezuela were not receiving it. Today, there is even a lack of HIV test kits in Venezuela, making it difficult to know just how many people have been infected since the beginning of the crisis.

“As more days go by, it’s going to be worse for us as people,” González Díaz said. “and I’m not saying this for my condition with HIV but for all people with illnesses. We really need medication.”