Maryland’s child support system, intended to sustain children, is actually hurting some of the state’s neediest families — especially in Baltimore, an investigation by The Baltimore Sun has found.

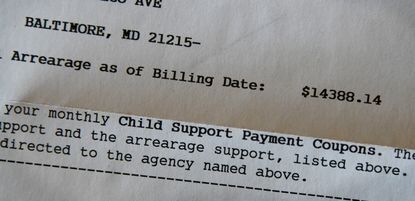

Under the dysfunctional system, parents in struggling city neighborhoods owe tens of millions of dollars in back child support — a whopping $33 million in one Northwest Baltimore ZIP code alone.

This debt has accumulated under policies widely seen as short-sighted, if not nonsensical. It often is owed by men who cannot afford to pay what the government has decided is due.

In a city with high levels of poverty and crime, child support is yet another corrosive force in Baltimore, an undertow invisible to most. Advocates and researchers agree: The system’s policies are not only hurting fathers, but are tearing apart families and pulling down neighborhoods. And experts say the weight of that debt winds up encouraging men to join the underground economy.

"They [policies] are completely counterproductive to family stability, safety, economic self-sufficiency and communities — particularly poor communities,” says Joe Jones, who runs a Baltimore center for families.

The Sun’s nine-month investigation found:

-

Many of Baltimore’s most challenged neighborhoods are saddled with massive child support debt. It is concentrated in 10 city ZIP codes, where about 15,000 parents collectively owe more than $233 million, according to The Sun’s analysis of state child support data. Much of it is regarded as unrecoverable because the debt is very old and owed by people who cannot pay.

-

When noncustodial parents, mostly dads, are unemployed, they are routinely ordered to pay child support based on “imputed” income, a calculation of what they could earn if they had a job. These fictitious earnings do not reflect the barriers that may prevent someone from getting a job, such as a lack of skills or a criminal record. And such orders ignore research that shows parents are more likely to comply with their child support order if it is based on their actual ability to pay.

-

In many cases, not all of the money the fathers are paying is going to the family. That is because the men must repay the government for welfare. The aid is essentially a loan.

-

Even though the federal government requires states to use at least a portion of child support collections to pay back welfare, there is a way for Maryland to end the policy. A national expert estimates it would cost Maryland only about $1 million to stop the policy going forward — and direct parents’ entire child support payments to their families, instead of the government. That is a sliver of the $2.4 billion budget of the state’s Department of Human Services, which administers welfare and child support programs.

-

If a parent falls behind on just two payments, officials can yank his driver’s license. The agency’s relentless collection bureaucracy can also suspend professional licenses for some occupations, including barbers, nursing assistants and plumbers. That makes it hard for the parents to get and keep jobs, and in turn pay their support.

-

Parents who go to prison can run up thousands of dollars of child support debt while incarcerated. A state law passed eight years ago authorized the child support agency to freeze support orders while someone serves time, but advocates say that often does not happen. The amassed debt drives men back to an underground economy — whether working as a carpenter under the table, or selling drugs. That way, they can earn cash to deliver directly to their families, rather than having the system automatically take money from their paychecks.

The child support system was designed to make sure parents do not evade their responsibility to support their children. For most families, the system works. But people who earn less than about $40,000 a year can easily fall behind and get ensnared in its aggressive enforcement machinery, experts say.

For these low-income parents, the system is riddled with policies that critics say are aimed more to punish fathers than to help children. The Census Bureau estimates that even as the child support system lifted 800,000 people across the country out of poverty in 2018, it pushed an additional 300,000 people into destitution.

To be sure, parents — both moms and dads — are expected to support their children. Some say they should not have had kids if they could not take care of them. Many fathers who run up big child support debt have made life choices that do not elicit sympathy.

Those left to raise the children, most often the mothers, say they are shouldering all the burden, and if they abandoned their children, they would be locked up.

In interviews with more than a dozen mothers, many say providing for a child is not about giving some diapers one day and new sneakers the next. They say kids need consistent emotional and financial support.

“I have to put the system in the middle to make you do your job as a dad,” Nikkia Jefferson-El said outside a Baltimore courtroom, where a judge considered holding her daughter’s father in contempt for not paying his order.

But mothers also say they see the system sometimes makes things worse. Locking men up or taking away their licenses is short-sighted, according to these mothers. They want the system to help, not hurt, their ex'es chances of making money.

As tensions grow between parents, a child suffers when the dad does not come around as much, or when the mom wants the dad to stay away until he pays her the money he owes.

Yet when some fathers decide to straighten out their lives, they carry such a daunting level of debt — owed not just to their families, but also to the government — that they give up, advocates say. These advocates argue for policies aimed at supporting men who are trying, if belatedly, to do the right thing.

Take Cecil Burton. The 54-year-old West Baltimore man is deeply in arrears to the state child support agency from years when he was struggling with a heroin addiction. When he got clean in 1999, he began working more steadily and tried to tackle his debt.

Because he was not able to pay the full amount, the system rescinded his right to drive, seized his tax refunds and threatened to put him in prison.

He is still paying down some $60,000 in debt — money due largely not to his ex-partner and kids, but to the government for welfare the children and their mother received over the years.

For the men who are deeply underground, Burton said, the system and its long enforcement arm do not hold any sway. Only for those trying to do right.

“Child support messes with the fathers who are actually working and trying to man up and pay the child support,” Burton said, “the fathers who are out there working and struggling, trying to make ends meet.”

Critics liken the state’s approach to trying to get blood from a turnip.

“We have got to, as a society, think about what makes business sense. What is in the best interest of a child? What is in the best interest of a neighborhood, of a community?” says Jones, founder of the Center for Urban Families in Baltimore and a national leader on child support reform.

While the government also collects child support from noncustodial mothers, the vast majority of cases involve fathers. In Baltimore, nearly all are African American, many of them poor and living in challenged Baltimore neighborhoods.

Map: Concentration of child support debt in Baltimore

The issue has drawn the attention of Maryland officials, including those in races for mayor and City Council, as well as members of the General Assembly.

State Del. Nick Mosby, a Baltimore Democrat who is running for City Council president, says the child support system “perpetuates a cycle of poverty and it perpetuates a cycle of criminal activity.”

Some contend these policies are mostly designed to punish a stereotype — the deadbeat dad — when in fact the problem is the system has not been able to distinguish between those who are avoiding payment and those who simply cannot pay what is due.

Across the country, states are wrestling with the same issues. Some, like Minnesota, Colorado, California and even Maryland have tried pilot projects and legislative fixes. But most of these have been marginal changes. In Maryland and elsewhere, even with evidence that the program is not working for poor families, the problems have been allowed to fester for decades.

Last year, legislators including state Del. Kathleen Dumais, a Montgomery County Democrat, pushed in the Maryland General Assembly for a package of bills. She and others are concerned the system is creating more problems for deeply poor families. They proposed limiting the use of fictitious, or imputed income, for instance, and making orders more realistic for low-income parents.

None of the bills passed. Supporters attribute that to their complexity and the resistance among some lawmakers, who considered the problems the fault of so-called “deadbeat dads.” More legislation has been introduced this year.

In interviews, Department of Human Services officials defended their work, saying the system is successful at delivering parental financial support to tens of thousands of families across the state. But they acknowledged there are problems for poor families that need to be addressed.

“The goal is to establish the orders based on the ability to pay,” says Kevin Guistwite, who runs the department’s Child Support Administration.

Despite their public role and their significant power in setting orders and imposing sanctions, Baltimore’s Circuit Court judges declined multiple requests made in person, over the phone and by email to answer questions for this article. The judiciary’s spokeswoman, Terri Charles, did not give any explanation as for why the judges declined to be interviewed. After asking for the questions in writing, they later decided not to answer them.

Meanwhile, across the city, community leaders see the consequences. In West Baltimore, at the families center, Jones tries to help dads who are afraid of being arrested because of unpaid support and worried about losing their jobs because of unreliable transportation. And they are also upset about being estranged from their children because they cannot meet the demands of a system they see as stacked against them. Jones says in some cases, parents decide to deal drugs to pay their child support and other bills.

In East Baltimore, at the Men and Families Center, director Leon Purnell says men come to him, hopeless, with pay stubs that show after two weeks of work, they only have $2 left. Child support frequently ruins their credit, which can make it hard for them to get housing. And when they have a place to live, he says, they can be evicted if their paychecks come up short from the wage garnishments. Their desperation feeds addictions.

Purnell has seen fathers do much more for their children than the child support system gives them credit for. They take their kids to school, or pick them up. They love and encourage them. They cook them meals and buy them necessities. He has known men to show up in court with a cigar box of receipts as proof for the support they have given their children, only to have judges disregard the evidence.

“The problem with child support is, it is really not about the child,” Purnell says. “It is about money.”

What just happened?

Here they are not mother and father.

In a small courtroom on the east side of North Calvert Street, officials refer to them as “custodial parent” and “noncustodial parent.” And after a proceeding that may last just seven or eight minutes, a judge will decide how much one must pay the other, usually the man to the woman.

The child support order is often unrealistic. Also capricious. Parents are left wondering, What just happened?

A man without a job could be told to pay $20 a month. Another man could be ordered to pay $200. The state has guidelines, but they are a decade old and judges have wide discretion to decide for themselves.

Researchers track the use of this fictitious income, officially called “imputed income.” A 2018 University of Maryland study found that as many as a fourth of child support orders across Maryland were based on these imaginary earnings. In Baltimore, half of all orders were said to be imputed.

Such orders often assume the parent has a full-time job earning at least minimum wage. Supporters of this practice say it reflects a likelihood that fathers are earning some under-the-table income.

Although newer data is not available to show its prevalence, the Maryland system continues to rely on imputed income. This is despite federal policy that the support orders should be based on actual earnings and evidence of ability to pay.

While meant to encourage the men to get jobs, advocates say the tactic of imputed income often backfires because it creates hopeless situations for people who are chronically underemployed and living unstable lives.

Believing that such orders will motivate parents to “go and get a job" represents "a fundamental misconception on why people work and don’t work,” says Vicki Turetsky, who ran the U.S. child support office during the Obama administration.

“‘I am told to do this, but really there is no option for me to do this,’” she says. The thinking becomes, “ ‘I can’t do this.’ ”

Parents whose orders were based on imputed income paid less than a third of the money they owed for child support, the University of Maryland researchers found.

But when a parent’s actual income was used to establish an order, they paid two-thirds of their obligation and got in less debt, said Letitia Logan Passarella, research director at the School of Social Work’s Center for Families and Children.

Whether Maryland judges know about the research is unclear, because they declined to answer questions for this investigation.

Passarella’s team analyzes data for the state under a contract with the Department of Human Services. The researchers have found that once a parent is earning more than $40,000, the child support system tends to work, and the money gets paid.

But many dads, born into poverty and often young when they had their children, get in over their heads.

Especially if their families sign up for welfare.

Welfare payback

Most people think of welfare as a handout. In fact, the child support system expects families — specifically the noncustodial parents — to pay it back.

The rationale for the policy was described in a 1971 address in Congress by the late Louisiana Sen. Russell Long, a Democrat who called it “brutally unfair” to ask taxpayers to "support the children of the deadbeats who abandon them to welfare.”

The child support system was set up a few years later with two purposes. The first was to ensure dads were supporting their kids through formal payments to their moms. The second was to force fathers to repay the government for any benefits their families received.

While most of the money the system collects now goes to the mothers who are taking care of the kids, a significant chunk is collected to pay back welfare.

But it is an illusion to think a parent with little education, no skills and no job likely can pay back the government, advocates and researchers say.

“There is a competition that gets set up between the family’s needs and the government’s cost recovery politics,” Turetsky says.

“The mother of his children says, ‘They need new winter boots.’ The father says, ‘I don’t have it.’ And the reason why he doesn’t have it is he is trying to stay out of trouble by complying with his formal obligation — which is money going to the state.”

When a woman signs up for Temporary Cash Assistance, with few exceptions, such as if she is a victim of domestic violence, she must give the state the father’s name, birthday, address, a photo, a description of his tattoos — any information she knows. That will be used to track him down.

The state is no regular debt collector. It hounds the fathers, ruining their credit, even if they are making partial payments when they cannot pay in full.

Until recently, as long as a mother and children were receiving welfare, Maryland claimed the entire child support payment by the noncustodial father to replenish government coffers.

The federal government has since 2008 allowed states to make sure that some money from the father goes first to his family. Maryland finally decided to do that with a state law that took effect July 1.

Under the law, the first $100 of a parent’s monthly payment — $200 if there is more than one child — goes to the family. The remaining portion of the father’s child support order goes to the government.

Cecil Burton’s welfare debt began to mount three decades ago, when he was in his 20s.

He was living with the mother of three of his four kids, Printess Doughty, when she first went for public assistance. Never married, the couple was broke. Burton had a worsening addiction and only sporadic employment.

Soon after Doughty signed up for aid, Burton started receiving bills from the child support agency treating the assistance like a loan. By the time their kids were all but grown, he says, the tally had risen to $60,000.

He says he began trying in earnest to pay that debt at 34, when he stopped using drugs. He held various jobs, including driving a shuttle for an addiction treatment center. But he says the state garnished so much of his paycheck for child support he did not have enough to live on. One payday, his colleagues passed around a hat for him.

Letters from the government warned he could be sent to prison if he did not pay. But his debt was more money than he could imagine ever earning, much less paying back. For years, he bounced between payroll jobs and under-the-table work.

Doughty says she never wanted her decision to pursue Temporary Cash Assistance to turn into a life sentence for Burton.

“I could see back then he was trying,” said Doughty, 52, a school bus monitor from Northeast Baltimore. She said child support has dragged down many men in her family, including her nephew and her grandchildren’s fathers.

“You want to beat up these fathers that ain’t got a dime in their pocket right now?” she said. “They’re struggling to get themselves from point A to point B, to keep themselves from drowning. You’re going to make them drown.”

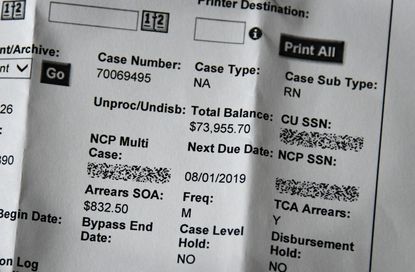

The state has about 16,500 cases like Burton’s that are set up for welfare cost recovery, almost half of them in Baltimore.

The debt these parents carry is heavy. Collectively in Maryland, they owe the government $156 million in back child support to repay welfare benefits, including $73 million in Baltimore, The Sun’s analysis found.

While a national child support expert says the state could choose to forgo the right to collect some of this money — writing off the uncollectible debt, as any company would — without federal penalty, the state has not done that. But it has set up a program so parents can apply individually to forgive their debt through consistent payments.

About 230 Maryland parents eliminated their welfare debt last year and an additional 200 entered agreements to try. Thousands more are believed to be eligible.

Advocates say the program could be publicized better, though they also say many fathers are so suspicious of the agency they might be wary of participating. And the requirements to get relief are rigid, and for many, it has been rife with problems.

Burton is on the payment plan as he continues to try, now in his 50s with his kids grown, to finally get out from under the debt.

Child support records show Burton made the payments, largely through automatic deductions from his pay working at a lumberyard. But when it came time for the first half of his debt to be erased, it did not happen. State officials declined to comment on the case.

After months and multiple visits to the child support office to make sure his debt was reduced and his driver’s license suspension lifted, he is as tangled up as ever in the system.

Losing a license

The government worker was determined to collect $300 toward the $75,000 Craig Ireland owed in back child support for his 20-year-old twin daughters.

Ireland tried to reason with her. He showed her the letter from a moving company that promised to hire him at $15 an hour if the agency would lift the suspension of his driver’s license.

The worker would not budge. Pay first, she insisted.

He told her he did not have the money. Exasperated, Ireland left the office.

“They’re basically saying, ‘We are going to need you to give us some money before we let you go to work,’” he says. “But if you don’t release my license and I don’t get the job, I am in the same sinking boat.”

By the time he came up with the $300, the moving company had given the job to someone else.

Ireland, now 47, is still without his license. After working for years in the underground economy, he says he is trying to transition to a job on the payroll to make a clean and final break with his past life.

At a single point in time, in September 2018, nearly 40,000 people had their driver’s license suspended by Maryland’s child support agency, according to data obtained by The Sun through the public records request. More than a third of those drivers lived in Baltimore.

The idea is to pressure noncustodial parents into making payments ordered by the court. But critics fault the policy as counterproductive.

“We think we’re going to get more child support by taking someone’s license away?” asks state Del. David Moon, a Montgomery County Democrat.

The suspension process is triggered if a parent falls 60 days behind in payments. Child support officials send a notice warning that unless the debt is paid — or the parent seeks and receives an exemption — his license will be suspended.

The parent has 30 days to act. After that, suspension by the Motor Vehicle Administration is automatic.

“Someone isn’t having their license suspended without us attempting to communicate and reach out to them,” says Katherine Morris, a spokeswoman for the human services department. “You’re getting contacted. You’re being told the situation, that you need to address it. ‘Reach out to us, give us a call.’

“When that doesn’t happen and it’s not paid, it’s suspended.”

Advocates say the system is fraught with problems. Parents do not always get the notice, because, being poor, they are also often transient. Many men are reluctant to visit the agency, believing they will be jailed for owing child support.

And then there are bureaucratic mix-ups. Some parents say they have been assured by a child support worker that their license was reinstated, only to find out during a traffic stop that that was not true.

Besides driving privileges, the state also can pull professional and recreational licenses if a parent is not paying their child support.

Some 1,900 professional and recreational licenses were suspended by the state, including 750 in Baltimore, in September 2018, the data shows.

Statewide, about 320 licenses were for certified medication technicians. An additional 150 were rideshare licenses. About 225 barbers and 120 certified nursing assistants had their occupational privileges blocked.

Guistwite says his agency wants to work with parents so that their orders get paid and their kids get the resources they need. He said parents need to come to the office to explain problems before the agency takes enforcement actions.

Even so, Guistwite concedes the practice of suspending licenses is not without faults and says adjustments to agency policy may be worthwhile. “We’re open to considering anything that would make sense,” Guistwite says. “How we could help the families is certainly our key goal.”

Behind bars, debt piles up

Perhaps the most counterproductive strategy in the system — one that Maryland lawmakers have tried to fix — happens if a parent with a child support order goes to prison.

It is an impossible dilemma on both sides. For the parent left behind, usually the mom, she must take care of the child alone.

“They don’t have a choice. They have to keep a roof over that child’s head. They have to feed that child. And if they don’t, the child can be removed from them,” said Laure Ruth, legal director of the Women’s Law Center of Maryland.

But the problem is compounded because when a father is imprisoned, the child support debt can still pile up, month after month. And when the parent is released, he has often built up significant debt, routinely as much as $20,000.

With little ability to pay that money, many believe, the men are set up to fail. That includes Ruth from the Women’s Law Center and many of the mothers.

“When they step back in the world, they’re lost,” says Printess Doughty, Cecil Burton’s ex-partner, whose frustrations with the system and its effect on her family stretch over decades.

“They might go to Amazon or work at Walmart and push some carts, try to change their lives, but how can they? Every time he gets his paycheck there is nothing to live on. You make a person say, ‘I’m done.’”

The scope of the problem has been huge. Much of the unpaid child support nationally — and about a quarter of the debt in Maryland — was estimated to be owed by parents who are or have been in prison. In Baltimore, a 2005 University of Maryland study found the proportion was even higher, about 40 percent.

“Orders are supposed to be based on ability to pay," Turetsky, the former child support czar, says. "Just because you go to prison, it doesn’t mean the child support program is there to continue to punish you.”

She stresses that suspending monthly payment orders until an inmate is released — including money owed to a former spouse or partner — “doesn’t mean the custodial parent will be hurt.” That is because in most of the cases, there is no money. She said the belief that it can be paid off, and that the children will benefit, is a myth.

Even lawmakers agreed and tried to change the system.

Eight years ago, the legislature passed a bill, signed by then-Gov. Martin O’Malley, a Democrat, to freeze child support orders when a parent is sentenced to 18 months or longer in prison.

But it became clear to advocates for prisoners that the new Maryland law was not reaching the number of inmates legislators had hoped.

Devin Carr of Baltimore continued to get collection notices from Maryland’s child support agency while serving a seven-year sentence in a federal prison in West Virginia. Carr, now 33, pleaded guilty in 2013 to making a deal with an undercover agent and a government informant to rob a cocaine stash house.

“I don’t expect no pity,” Carr says. But he thought that while he was in prison, the state would understand "‘there is no way he can make these payments right now.’”

That is what advocates who fought for the legislation thought, too. But after advice from the Maryland attorney general, state officials decided the new law would not apply to most prisoners. Instead, reprieves would be granted only to parents whose child support orders, as well as their prison sentences, were imposed after the law took effect.

That meant someone like Carr, who had two existing child support orders, was not eligible. His child support debt grew to $25,000 while in prison, Carr says. Released in April, he got a job in an auto parts warehouse making about $700 a week, taking home about $450 after child support and taxes. Even so, he was barely touching his arrears debt.

Carr says he ached for his three children while he was in prison, and as soon as he got out, he tried to rebuild relationships with them and navigate tensions with their mothers. He says they spent time together with trips to the movies and weekends at his house.

In a recent interview, former Maryland Attorney General Doug Gansler, a Democrat, defended his advice. Gansler said that while he supported the legislation, his job was to make sure the law’s passage did not put into jeopardy any of the state’s federal funding.

Guistwite, who runs the department’s Child Support Administration, said he believes that the accumulation of uncollectible debt while these parents are in prison serves no one. In an emailed response to questions from The Sun, the agency said workers have been told to review population lists from the prison system to look for matches with the child support caseload. If they are found, the agency can administratively suspend some orders.

The agency also supports a bill now in the General Assembly that would reduce to six months the sentence under which prisoners could have their child support orders frozen, down from Maryland’s current 18-month standard.

But the state Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services still has no policy in place for administering the 2012 law, according to a spokesman. Caseworkers in the prisons refer inmates to a small Baltimore nonprofit, Alternative Directions Inc. It is not legal help, but its workers advise individual inmates how to advocate to have their orders frozen.

Of the thousands of inmates believed to be eligible, the nonprofit has been able to help a few hundred parents. But even among those who should have qualified, some report they are still getting bills.

Advocates say the state needs to perform an audit to figure out why the law is not working for more inmates.

'Give these guys a chance’

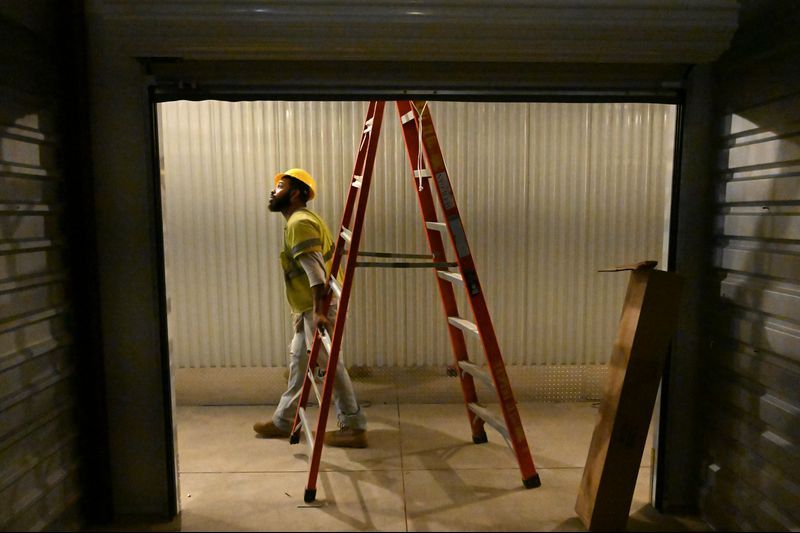

After a life defined in part by poor choices, parents who make a change and get a job can find themselves pulled under again.

Arthur Gilliam, who grew up in a Baltimore public housing high rise and lost his mother when he was 10, was in and out of prison for stealing cars, and later for gun possession. He said he was troubled, but in his 30s, he committed to changing, for himself and his kids.

In the past year, he got a job training to be an electrician. On a bright fall day, after working his morning shift in a building in southwest Baltimore, Gilliam stopped in a nearby McDonald’s for lunch. His face was lit by a big smile. He knew all the workers, chatting and making jokes with them.

Working in effect as an electrician’s helper, Gilliam was being paid $13 an hour, about $27,000 a year before taxes. But the child support system garnished a third of his paycheck for current and back child support. That left him a gross income of $1,500 a month. He was shocked how little he had left.

That is the point at which advocates and researchers say the real consequences come into play. For fathers who are trying to get established on a new path, the system’s punitive actions can create the very behaviors everyone wants to avoid.

Demoralized, Gilliam quit the job a few weeks later. He said he planned to apply to a program to become an electrician’s apprentice while continuing to work odd jobs, as he has always done, to support himself.

But in a recent interview on the street outside his home in East Baltimore, his beard was scruffy, his affect flat. He said he felt sad, and ashamed. Gilliam said he rented the rowhouse for $1,000 a month with hopes of having his kids stay there sometimes. But he knows their mothers are furious that he quit the job and stopped paying support, so he had not seen the children in months.

The owner of an engineering and construction firm who has hired many noncustodial dads says the impact extends far beyond the men and their families, to local businesses and the labor force.

“If you have a child, someone needs to take care of the child. But some of the child support, they take such a big chunk of their check that it’s not worth them coming to work. ... They don’t even have gas money to get to work,” says Rich Beattie, owner of Mechanical Engineering & Construction Corp. in Catonsville. Beattie stressed he was not arguing against child support orders. “I am thinking there has to be some limit on what the support can be.”

He noted that his company offers men a path to a well-paying career, if they can stick with it. “A plumber would make $40,000 to $80,000 anywhere in the country. Having them quit because it’s cheaper to stay home — that is not serving anyone’s interest.”

Kenyatta Davis, the mother of four of Gilliam’s five children, says she has been left to make sure their children are cared for — emotionally and financially. She blames him for squandering opportunities over the years and acting selfishly. But she also blames the child support system, and believes it has given Gilliam too many chances: “The state is doing the bare minimum. All it is, is broken promises and fake threats.”

Turetsky, who led the U.S. child support office under President Barack Obama, a Democrat, agrees Maryland and other states could do far more. She suggests using the system to bring families together and help get low-income men on better footing. That, in turn, helps their kids.

“It is often said about prison, ‘Why not take advantage of the time to help them get GEDs, to teach marketable skills, parenting skills.’ I will say the same thing about the child support system,” she says. “No child benefits if their loving parent checks out, avoids the whole system of child support and has conflict with the mother.”

Many of the children who were supposed to benefit from the system are now grown up — and they sometimes end up helping their aging fathers deal with their old orders. The debt does not go away when kids become adults, or through bankruptcy. And it can follow the fathers to the grave. In the past three years, almost 2,000 parents died, still owing child support.

Grown children, like Cecil Burton’s daughter Keisha, now 28, believe the system never took into account how their fathers cared for them and loved them.

From the time she was a girl, she thought of her father as her “superhero.” He crafted a homemade go-kart for her, so he could pull her along behind him. He has been the one she could always turn to, the one who would give her the last dollar in his wallet. She even tried on one occasion to walk from East Baltimore to the west side just to be with him.

Today, Keisha Burton says she wants to go find the officials who run the system. She wants them to see she is an adult, a mother, a certified nursing assistant. She can take care of herself. She and her siblings do not want her father pursued anymore.

“At least give these guys a chance,” she says. “Actually see what they’re able to pay, even if it’s a small portion. Every little bit counts.”

Data analysis for this story was done by Christine Zhang. Research assistant Ryan E. Little also contributed to this article. To review the data and computer code that generated the analysis used for this story, go to bsun.md/child-support-analysis.