Jaime Parada still remembers his parents’ tears the night in October 1988 that Gen. Augusto Pinochet lost the plebiscite that would have allowed him to remain in power. They joined their neighbors on the street in their tony neighborhood of Las Condes, bemoaning the fact that their country would no longer be the same.

A quarter century later, the son is doing all that he can to change Chile.

In 2012, Parada became the nation’s first openly gay elected official by winning a spot on the council in the traditionally conservative Providencia neighborhood. He works tirelessly as spokesman for gay rights group MOVILH, the Movement for Homosexual Integration and Liberation.

The group helped organize the eighth annual Open Mind Fest in early November, shortly before the first round of presidential elections. Thousands of young gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender Chileans gathered on four city blocks of walkway Paseo Bulnes near federal legislative offices and presidential palace La Moneda.

Attendees held hands, danced to the music pumping at the four stages, and cheered the group of drag queens who preened in front of a fountain and a statue of a Catholic leader. Parada explained that event organizers chose the location in part to send a message to politicians about the community’s voting clout.

The message was heeded. Five of the nine Presidential candidates attended the festival.

Parada, who in November published a memoir, “Yo, gay”, is not just interested in advocating for the rights of gay and lesbian Chileans, though.

Rather he wants to help the nation expand its definition of human rights from the dictatorship-era concept of torture and disappearances to a broader view that includes the concerns of people with disabilities, access to the Internet and a clean environment, among others.

“The violations were so many, were so large, that they installed the consciousness that the field of human rights only pertains to the dictatorship,” Parada said. “We haven’t succeeded in installing a standard of international human rights that includes, to be sure, violations in military regimes or authoritarian governments, but also the non-incorporation of minorities into civic life.”

The fast-talking, jeans-wearing councilman is part of a cadre of young Chileans who have grown up during and after the Pinochet dictatorship. Animated by the collective memory of that earlier, darker time, they are working in a variety of arenas to help Chile become a more open, just and inclusive society.

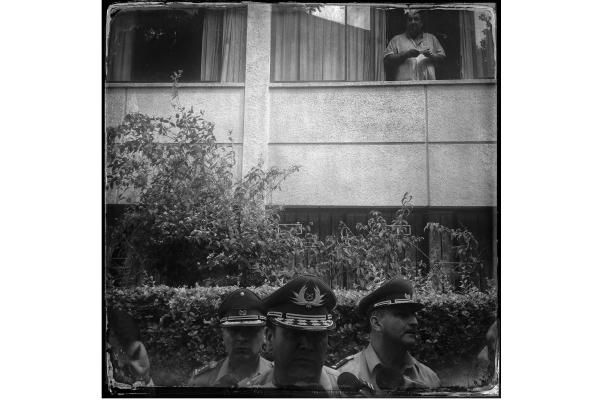

Separated in some cases by close to a generation, these groups and individuals have differing views on electoral politics. Parada served as the spokesman for progressive candidate Marco Enriquez-Ominami. But voting age members of student group ACES, the Coordinating Assembly of Secondary Students, who took over Michelle Bachelet’s campaign headquarters during the recent presidential election said they did not vote because they didn’t believe in any of the nine candidates.

The group seeks greater community control as part of its objective of transforming the Chilean educational system. About two dozen ACES members jumped up and down and chanted slogans denouncing the current system and leaders like Pinochet and Bachelet. “She represents the big businesses,” ACES spokeswoman Eloisa Gonzalez, 19 and a high school student in Santiago, said of the former president.

Many of the young changers who work in the non-profit sector share a national, and even international, consciousness. Non-government organization TECHO does a Habitat for Humanity-style blend of construction and collaborative community development work in 19 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, for instance. Started in 1997, the organization seeks to help individuals and neighborhoods overcome poverty. TECHO volunteers and staffers work with community members to diagnose needs and assets, and, from there to formulate a plan.

Blue-shirted volunteers, many of whom come from middle to upper-class backgrounds, spend weekends and other times working in campamentos, or shantytowns, throughout Santiago. Brick and mortar projects include building houses, a community center or a library. Some campamentos with a TECHO presence have tutoring programs and micro-enterprise stores.

Non-profit Ciudadano Inteligente, which seeks to empower citizens through using technology to give them access to information, also has strong global ties. Its office in the wealthy Providencia neighborhood resembles a Silicon Valley start-up space. Casually dressed staffers and volunteers work on Apple laptops and desktops with extended screens in every available nook of the two-story house. Yellow post-it notes describe projects’ trajectory line the wall. The sound of a ping pong ball bouncing on a table outside the house echoes into the kitchen.

Executive Director Felipe Heusser said that staffers relax together during work hours over a beer and some asado, or grilled meat, on many, if not most, Fridays. It’s part of an effort both to build an environment that fosters creativity and that differs from many traditional Chilean work sites, said Heusser, adding that this year the group has helped citizens file more than 1,000 requests under the landmark Transparency Act passed in 2009.

Ciudadano Inteligente’s mission points to another common element of the changers’ repertoire: the embrace of technology and the strategic use of social media. Each time Parada receives a threat on Facebook, he posts it on Twitter. Media coverage often follows. The students of ACES have close to 16,000 followers on Twitter, while leaders like Gonzalez and Melissa Sepulveda have an additional 20,000.

The degree to which these young Chileans will ultimately shape the directions their country takes is unclear. But what is not in doubt is their commitment to helping the country continue its arduous transition from a dictatorship to a vibrant democracy with an active, engaged citizenry.

For his part, Parada sounded an optimistic note about the country’s direction. “I think we are living a process of repoliticization, and because of this process of repoliticization, the force of certain demands are going to be much stronger,” he said. “That plays in favor of us.”