Editors Note: The following blog post was written by Anne-Michele Boyle, a World History teacher at Whitney M. Young Magnet High School in Chicago, IL. Boyle has spent the past two months connecting her students to "Fractured Lands: How the Arab World Came Apart" by Scott Anderson, with photos by Paolo Pellegrin.

Scott Anderson's "Fractured Lands" was the nexus of my World Studies classes for eight weeks. This powerful piece gave my students an indelible understanding of the Arab world while simultaneously providing a platform to improve critical thinking skills.

Before we delved into the reading, I implemented some of the pre-reading exercises the Pulitzer Center created. The identity ranking activity was particularly meaningful as students reflected and assessed how they identified themselves. This led to a fruitful discussion wherein students shared how they viewed themselves. Some students first identified themselves by their race, others gender, others ethnicity, others religion. Almost all the students considered age as a defining characteristic of their identities. We discussed how our experiences and backgrounds shaped how we viewed our identity.

Only one out of 130 students considered nationality as a defining aspect of their identity. So when we started reading "Fractured Lands" and got to know the characters, we synthesized what we knew about the character to make educated guesses about how they would fill out the identity list. For example, when we discussed Azar and Laila, we came to the conclusion that nationality would probably rank at the top of their list. This led to another meaningful conversation about nationality and why those who have to fight for their nations (or in Azar's case, to establish a state for a nation of people) often view nationality as a more important part of their identities, relatively speaking.

As we moved through the chapters, students answered the comprehension questions created by the Pulitzer Center. This was particularly helpful as the Flesch-Kinkaid reading tier for "Fractured Lands" is college level and my students are mostly highschool freshmen. Students found that the questions helped them more easily digest the material.

We concluded each chapter with a fresh discussion of that content and an assessment of how it connects to our lives in Chicago and the U.S. For example, when we discussed the factors that led Wakaz to join ISIS—generally peer pressure and a lack of economic opportunity—our dialogue organically moved to a comparison with what drives people to join gangs in Chicago. Largely, young men in Chicago are faced with the same motivators to join gangs: little hope, lack of economic opportunity and familial/social pressure.

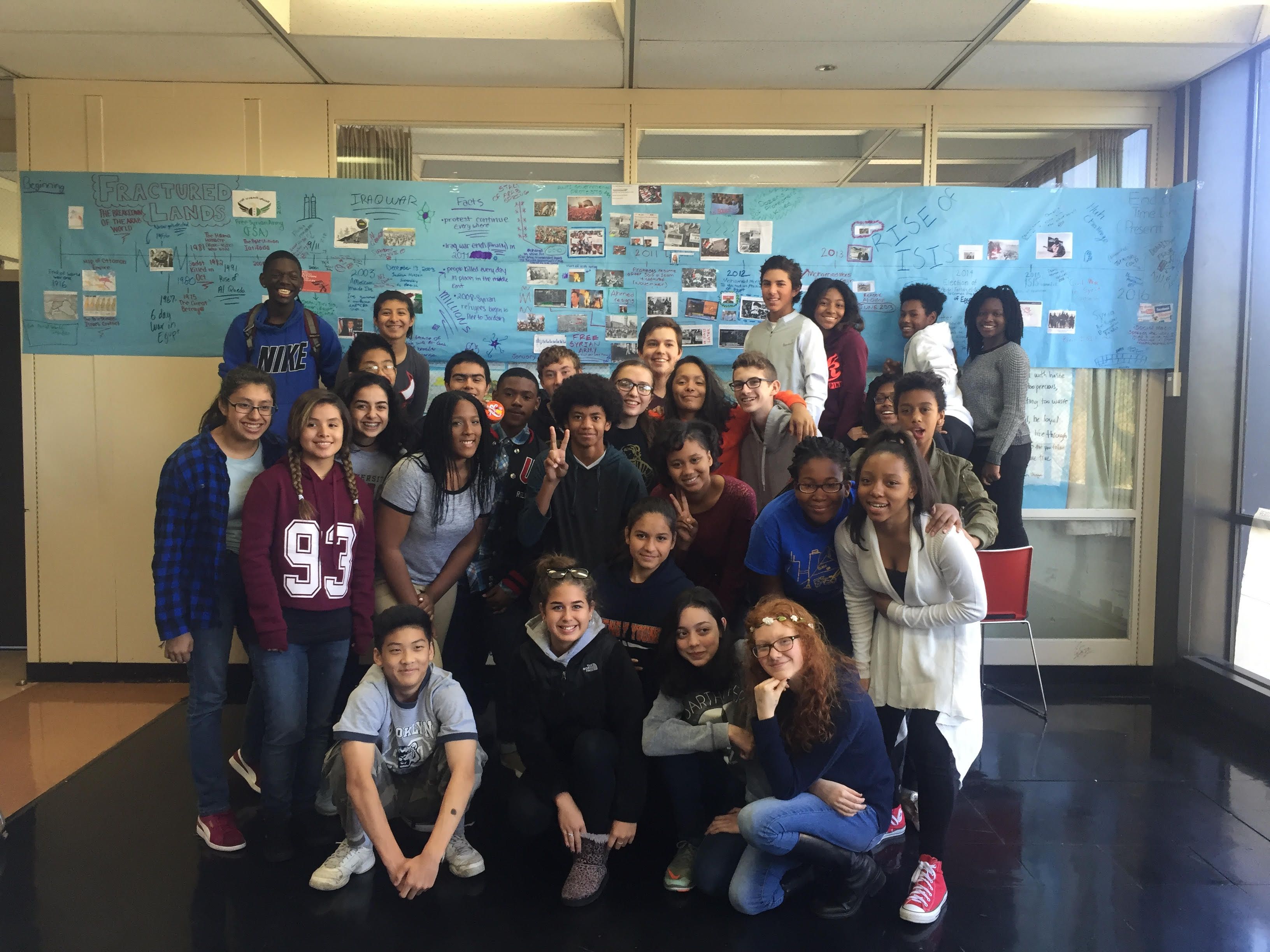

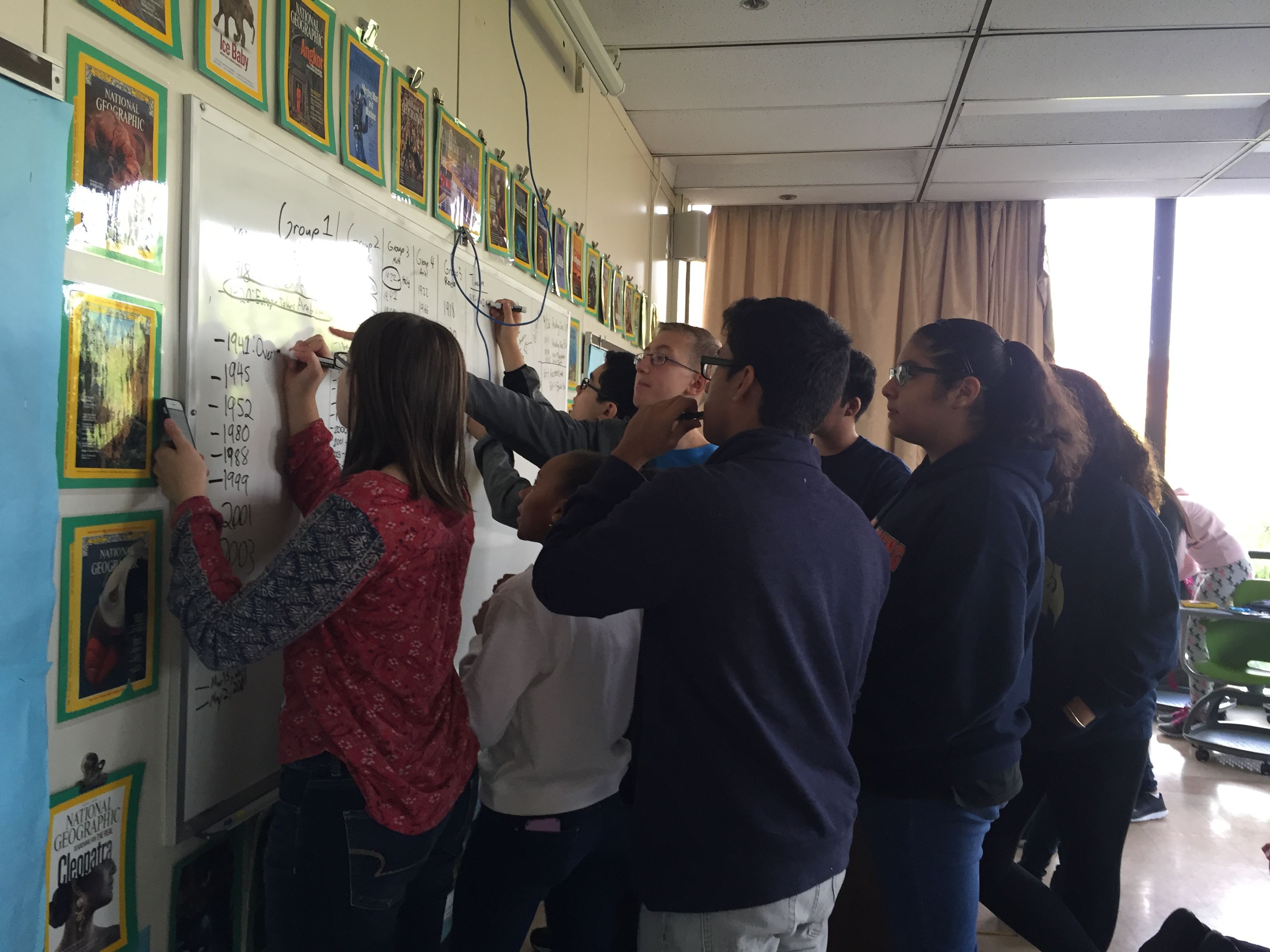

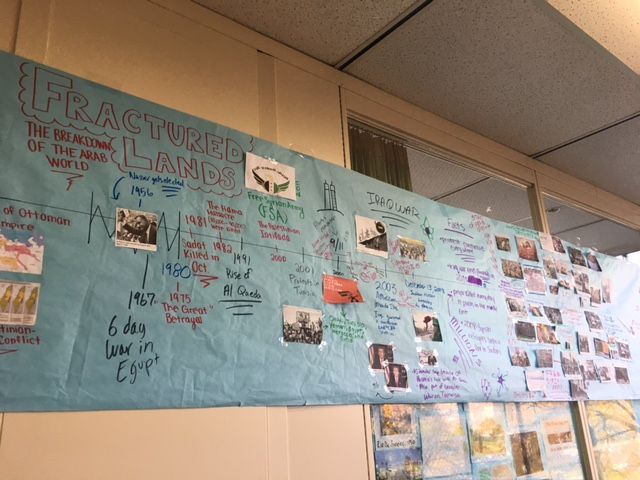

When we finished reading "Fractured Lands," we used 30 foot by 4 foot butcher paper to create a visual-heavy, text-light timeline that illustrated the factors, characteristics and effects of "the fractured" Arab World. We sprinkled in events that the students felt the "average" American was concerned with while the events on the timeline were occurring (i.e. NFL championships, Kardashians, etc.). Ultimately, students juxtaposed the American psyche of media consumption with the catastrophic events of the Middle East. This led to a dialogue exploring why this contrast exists. Click here to see my lesson plan I created for this exercise.

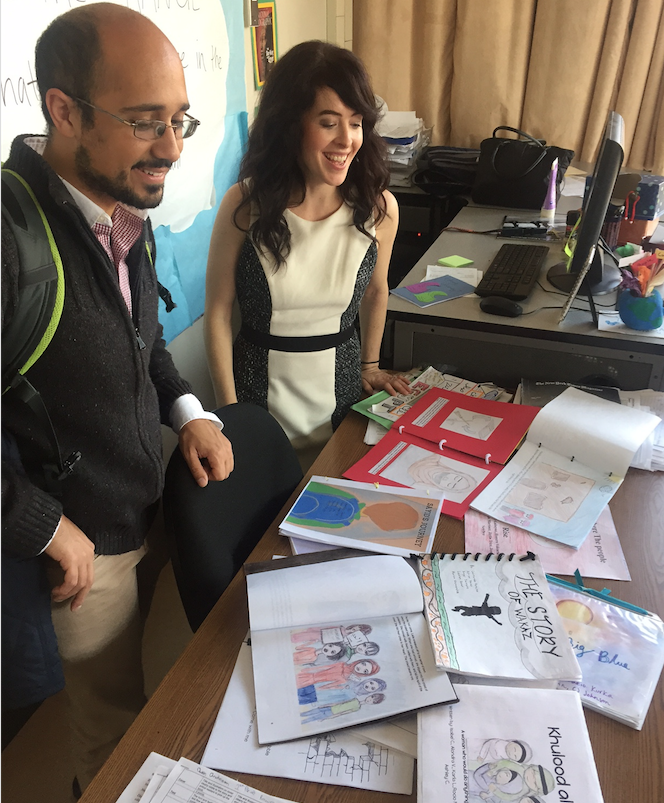

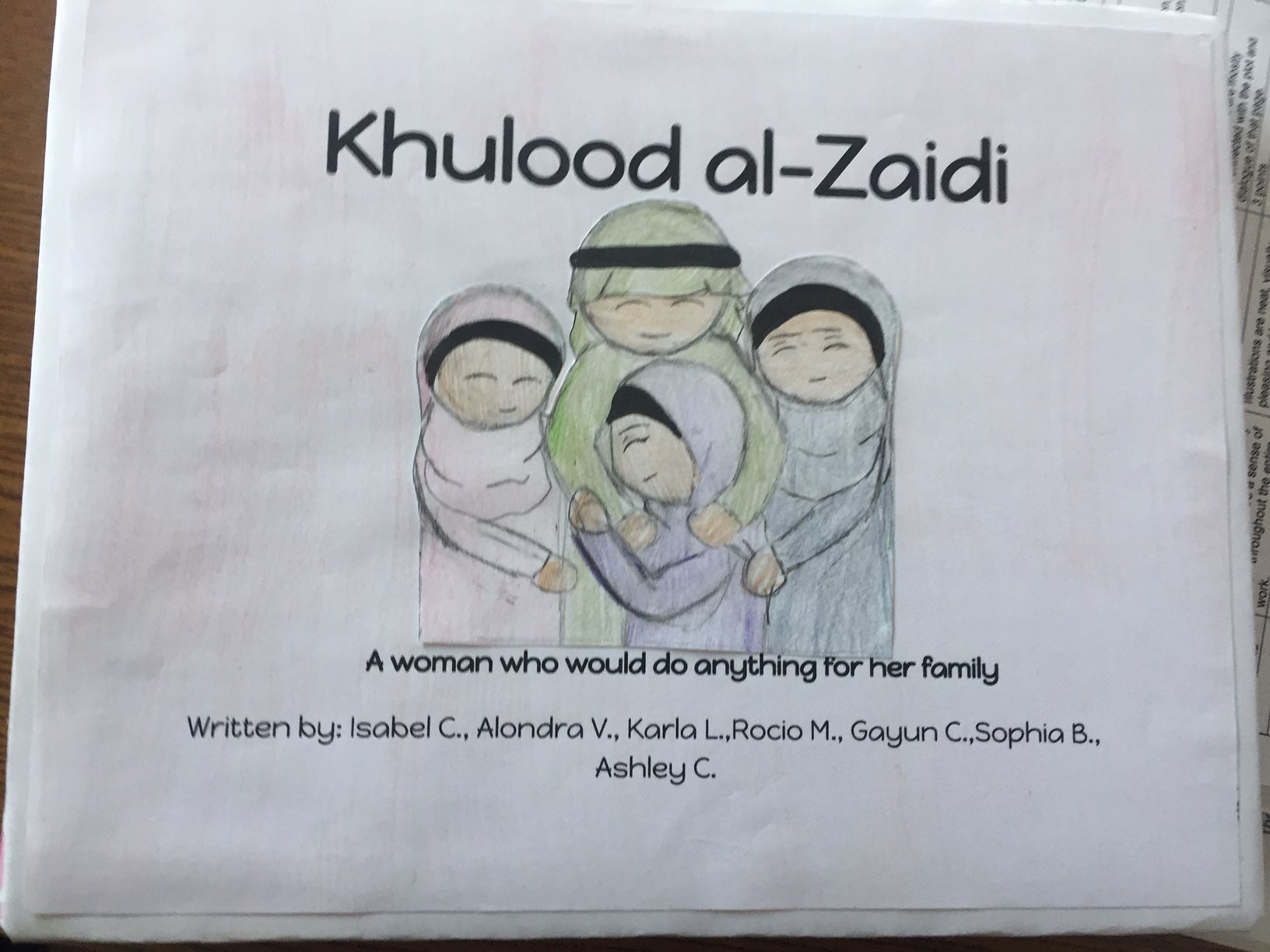

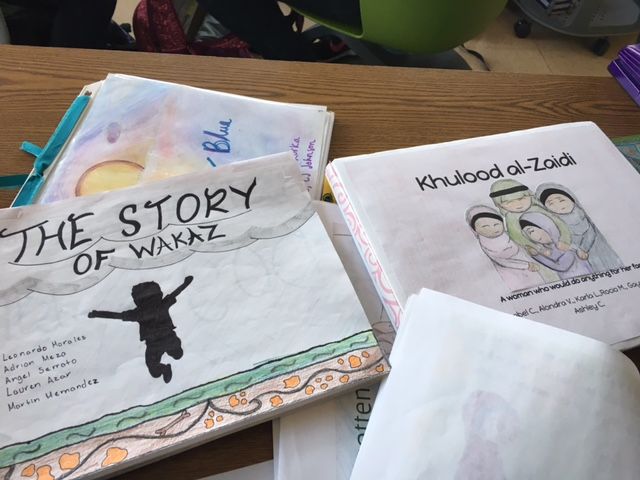

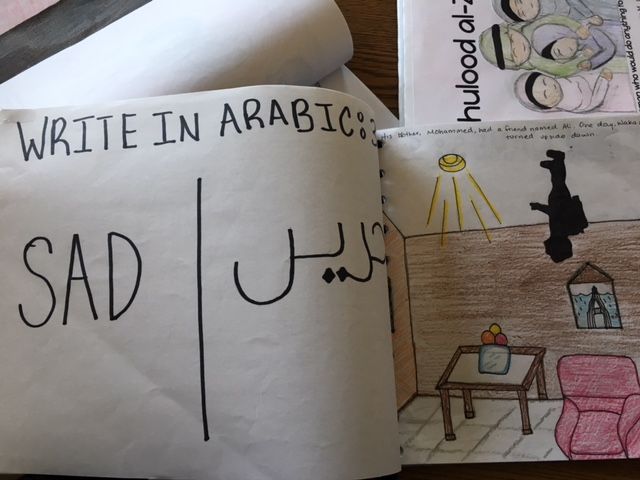

For our last project, students reflected on the topics (dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the Iraq War, the Arab Spring, ISIS, the refugee crisis, etc), individuals (Majdi, Laila, Majd, Wakaz, Azar, Khulood) and regions (Libya, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Kurdistan, Jordan, Tunisia) that are a part of "Fractured Lands" in order to identify what most interested them. Next, students found classmates with similar interests and brainstormed ideas for children’s books inspired by a topic/individual/region of “Fractured Lands.” While the general plot of each group’s children’s book was developed collaboratively, students' individual responsibilities were chosen by interest (i.e. illustrator, author, editor, researcher, etc). Some groups cooperated better than others, yet all students successfully synthesized this high-level piece into something more digestible for a younger audience and added their own creative spin. Students bonded, learned about team work and created some really impressive books.

The book topics and titles varied, but were all inspired by “Fractured Lands.” Khulood ended up being the most popular character students used to create historical fiction and non-fiction pieces. Other groups developed their own characters to tell stories ranging from the refugee experience to that of surviving war. Next up, students will share their books with local elementary schools. Using their books, students will be tasked with teaching younger audiences about the “Fractured Lands” of the Arab world. Click here for a description and grading rubric for this project.

Last week, and with much fanfare, Scott Anderson visited our school! Five hundred students, parents and teachers enjoyed hearing Scott's stories firsthand, seeing Paolo Pellegrin's photos on the big theater screen and connecting with Scott during our lively question and answer session. It was a stimulating and salient experience for all of us.

Through the process of working with “Fractured Lands,” students gained valuable insight and understanding of elements of the news that they were only peripherally aware of previously. Now when they hear Sinjar Province or Bashar al-Assad mentioned on the radio or on social media, they listen, they think, they speak and they share.

I would highly advise teachers to consider integrating “Fractured Lands” into their curricula. Not only does it provide real and timely content, but it also provides endless opportunities to improve skills such as critical reading, critical thinking, analysis and synthesis.