In 2017, well before the current pandemic began to dominate the 24-hour news cycle, a CommonSense Media study found that 63 percent of children experienced fear, anger, and/or sadness as a response to news. At the Pulitzer Center, we’ve heard similar concerns from our educator partners. Michelle Green, a middle school visual arts teacher at Jefferson Middle School Academy in Washington, D.C., agreed that her students’ mood has shifted in response to self-isolation and seemingly non-stop COVID-19 headlines. She said that her students are treating the news “agoraphobically” — or with anxiety characterized by fear and avoiding situations that might cause them to panic (the Mayo Clinic). “[They’re] hearing headlines and buzzwords but they’re not really being helped through what they're hearing,” she said.

Students know the importance of staying informed. The same CommonSense Media study found that more than half of students think that the news is important and helps them feel prepared to make a difference in their communities. The Pulitzer Center’s education mission is to cultivate a more curious, informed, empathetic, and engaged public by connecting students and teachers with under-reported global news stories and the journalists who cover them. So our challenge, perhaps more than ever, is to bring coverage of crucial, overlooked issues into classrooms without sowing anger, fear, or sadness.

Center programs support students in cultivating positive responses to news in three ways that are supported by research. The first way is by facilitating discussions that guide student reflection on the news. The second approach is leading workshops that support students in processing their responses to news through self-expression. The third approach is crafting opportunities for students to tell their own stories. Below, we’ll elaborate on how each strategy underpins our resources and initiatives for educators, including journalist visits, lesson plans, contests, and storytelling workshops.

Center Programs and Resources Guide Student Reflection

A 2017 study by Kleemans et al. showed that peer discussion can support students in cultivating more positive emotional reactions to the news. This study surveyed 336 Dutch pre-teens before and after participating in group discussion about a news story they had just watched, and showed that discussion led to enhanced positive emotions, reduced negative emotions, and increased confidence in their ability to effect social change. Our own experiences in the classroom support these findings as well — Pulitzer Center education resources widely employ discussion as a tool to help students process and respond to news stories, where our staff members begin the interaction with a warm-up discussion, work with journalists and educators to facilitate a discussion led by students and educators, and close with guided refletion and surveys that help students process and synthesize what emerged from their experience.

A student answers a question. Image by Claire Seaton. Washington, D.C., 2018.

Therefore, peer discussions are central to many of the Pulitzer Center’s education programs, particularly to the in-person and virtual journalist visits that we facilitate in classrooms around the country throughout the academic year. A typical journalist visit, in-person or via virtual platforms such as Google Meet or Zoom, involves the journalist giving a presentation on their reporting and methodology followed by Q&A and group discussion. We’ve improved these visits over the years with help from educators and students who provide feedback through post-presentation surveys, and whose feedbcack supports Kleemans et al.'s findings that discussion helps guide students toward less negative experiences of difficult topics in the news. “The presentation expanded student thoughts on global society issues with creative ways to approach these issues,” wrote an educator whose class was visited by the journalist who worked on a documentary titled “Circus Without Borders.” Another wrote that “students made personal connections on suicide and poverty...and were very engaged with the workshops and were heard talking about the news independently after the experience.”

Dr. Seema Yasmin discusses how a free press serves as the immune system of a democracy with students. United States, 2020.

In a special webinar series on "Under-reported Stories of Resilience" during the 2020 spring of remote learning, Pulitzer Center Education has chosen to center what Kleemans et al. call "constructive news" — stories with a solutions focus, or otherwise positive emphasis on how people around the world make a difference in their communities in times of crisis. The study found that students who encounter and discuss "constructive news" like this show increased confidence in their ability to effect social change.

In a survey following a webinar with photojournalist Pablo Albarenga, who shared his reporting on "How Indigenous Youth Defend the Amazon," students wrote that they were inspired by learning that “so many younger people were trying to make a difference” and that “It was great to know that others my age are fighting for their homes.”

Finally, our work emphasizes peer discussion and reflection in the form of our lesson plans, which include multiple ways for students to process news stories in small groups and as a class. Our team regularly adds new lesson plans to our Lesson Builder, where educators can find guided structures for class-wide warm-ups, reading comprehension, and discussion questions related to under-reported stories from our archives. The discussion questions generally move from asking students to recall details, to guiding students in evaluating the structure and composition of the news story, and then making personal and/or local connections to the story.

Programs for Student Expression and Active Learning

A 2014 study about fear in the classroom by Bledsoe and Baskin supports the use of a second strategy we use to helping students process news positively: providing opportunities for research and self-expression. Our lesson plans conclude with 2-3 extension activities, which model ways that students can apply the content from the lesson and share their own reflections through research, writing, visual art, and more. These are what Bledsoe and Baskin call "active learning strategies," or ones that emphasize a “democratic feel.” An example the authors provide is when students are “assigned a particular problem or question to research in groups, and develop a short presentation and share with the class” (Bledsoe and Baskin 2014, 39). Educators can find activities matching this description in many of our lesson plans, from chances for students to look into their local civil asset forfeiture laws to researching how the struggle for women’s rights manifests in their community.

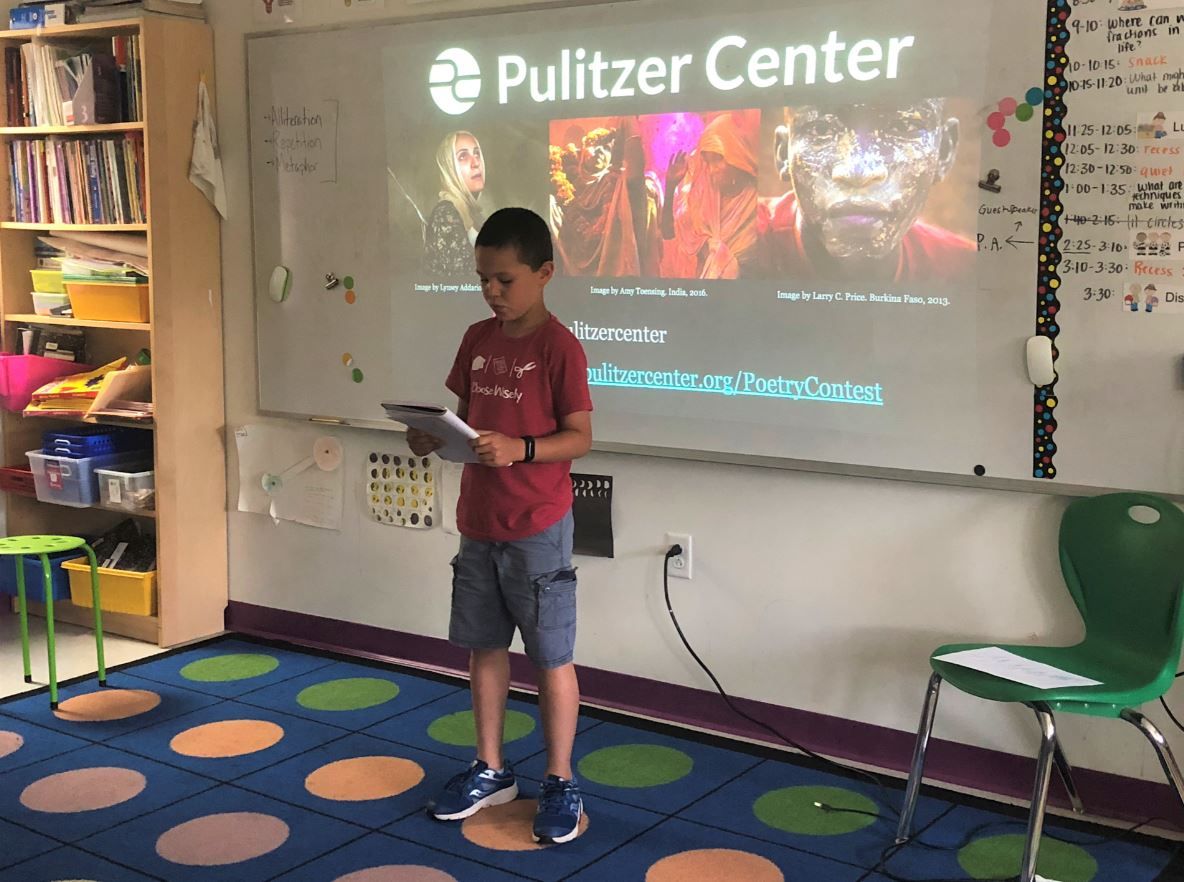

The Center has developed two annual contests that also guide students in working on expressive projects in response to news stories. Both Local Letters for Global Change and Fighting Words ask students to base either a letter or a poem on any piece of Pulitzer Center-supported reporting that they’re drawn to. Local Letters for Global Change, taking place yearly in the fall, asks students to write a letter asking a representative or community leader to take action on an issue that they feel passionate about. It emphasizes civic responsibility and the power of persuasive writing to affect change, and winners and finalists received publication as well as cash prizes.

Local Letters exemplifies Bledsoe and Baskin’s idea of an “active learning strategy” by decentralizing the educator as the “sole source of wisdom” and encouraging students to draw on their own knowledge and passions. Furthermore, this exercise gives students the opportunity to respond to often heavy reporting by exercising their voices and powers of persuasion. In short, this contest builds positive responses in students where they feel empowerment and purpose after engaging with an difficult topics.

Our annual spring contest, Fighting Words, also builds positive feelings in students learning about important under-reported stories according to Bledsoe and Baskin’s findings, but also takes advantage of the documented socio-emotional benefits of writing poetry. To enter, students use at least one phrase from a Pulitzer Center-supported story to compose an original poem that captures the feeling of the reporting. Each year, several hundred poems are submitted that reflect the poets’ personal connections to diverse news stories. Author Elena Aguilar writes for Edutopia that “[a] well-crafted phrase or two in a poem can help us see an experience in an entirely new way. We can gain insight that has evaded us many times, that gives us new understanding and strength.” Fighting Words, then, uses poetry as an avenue towards positive feelings like understanding, empathy, and strength for students exposed to potentially distressing news stories.

Workshops that Empower Students to Tell Their Own Stories

Finally, a survey of Israeli children conducted by Alon-Tirosh et al. found that students wish to be exposed to the news, but in a way that “avoids a condescending or infantilizing tone.” Further, the students surveyed wished “to be treated in a serious and authoritative manner.” The Pulitzer Center offers student workshops designed to build the storytelling skills that professional journalists use in their reporting. More than that, these workshops empower students to tell important stories themselves: the ones of their lives and communities.

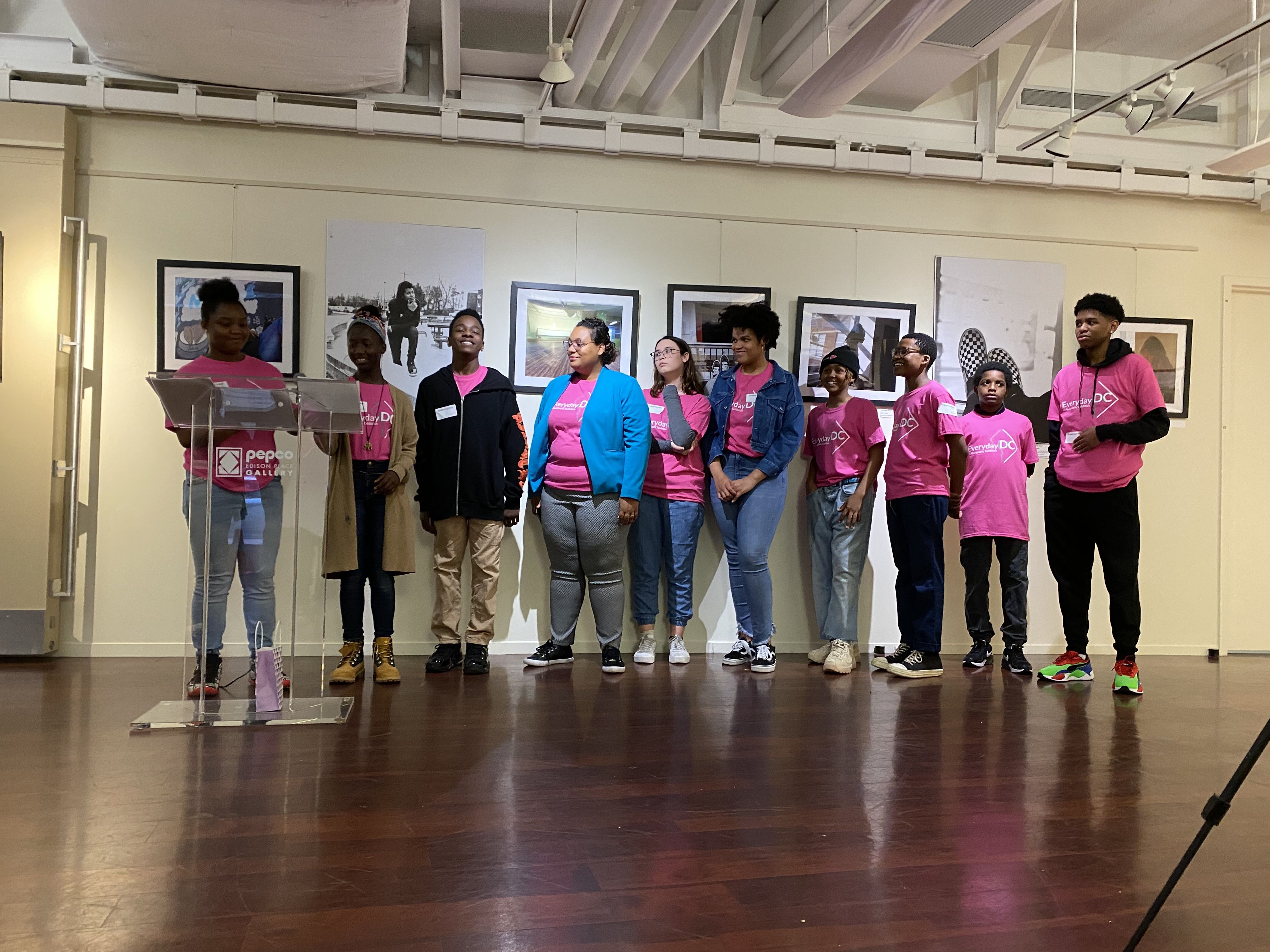

From Everyday DC to Walk Like a Journalist to Chicago HomeStories, these programs present a chance for students to contribute to and reshape pervasive media narratives. For students in Washington D.C. — whose communities are often only represented by images of crime and poverty, or of politics and glittering monuments — the Everyday DC unit teaches photojournalism skills culminating in an annual exhibition where students depict the story of the District through their own eyes on gallery walls for the whole city to see. Therefore, these programs fulfill students’ desires to be treated as storytellers rather than just consumers of news. Such feelings of empowerment and trust in themselves help to counteract the often-negative responses elicited from students who are not supported in their consumption and responses to the news, and allow peers and adults alike to learn from their vision.

The Everyday DC student curators give their opening address, outlining the exhibition's background, aims, as well as their curation process. Photo by Lea Waldridge.

Michelle Green, who has integrated the Everyday DC curriculum into her classes for many years, told Pulitzer Center Education that “the benefit with Everyday DC is, and why I’ve felt comfortable adapting it year after year, is that it’s always able to be adapted to the current times.” Since distance learning began, she has found the curriculum’s ideas a useful method to check in on her students’ “Everyday Quarantine.”

Students find themselves treated as storytellers themselves when they experience programs like Walk Like a Journalist and HomeStories as well. Both are initiatives which teach close observation and descriptive writing about students’ local communities. All of our storytelling workshops, whether focused on photojournalism, interviewing, or descriptive writing skills, support Alon-Tirosh et al.’s finding that students wish to be treated not as passive recipients of often-distressing news. Instead, our programs uplift student voices and empower them to shape the narrative of their communities themselves.

Students at Washington Global Public Charter School practice journalism skills in a Pulitzer Center workshop. Image by Eslah Attar. United States, 2017.

The same CommonSense Media study which showed that many students’ first reaction to the news is often one of fear, anger, or sadness also found that 50% of children surveyed “say that following the news helps them feel prepared to make a difference in their communities.” Other researchers have publicized strategies for mitigating negative emotional responses to the news, many of which are regularly employed in Pulitzer Center education programs. And it is in using these same strategies that we are able to connect students to crucial under-reported global news stories while at the same time uplifting, supporting, and empowering students.

We are always seeking feedback on how we can better support students' engagement with news and under-reported stories, please contact us here with ideas, or to collaborate.