In Algiers four years ago, Sufyian Barhoumi’s mother found him a bride. His brothers bought kitchenware to help him open a pizza parlor.

Now all Mr. Barhoumi needs is a way out of the United States military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, where he has been held for the last 18 years.

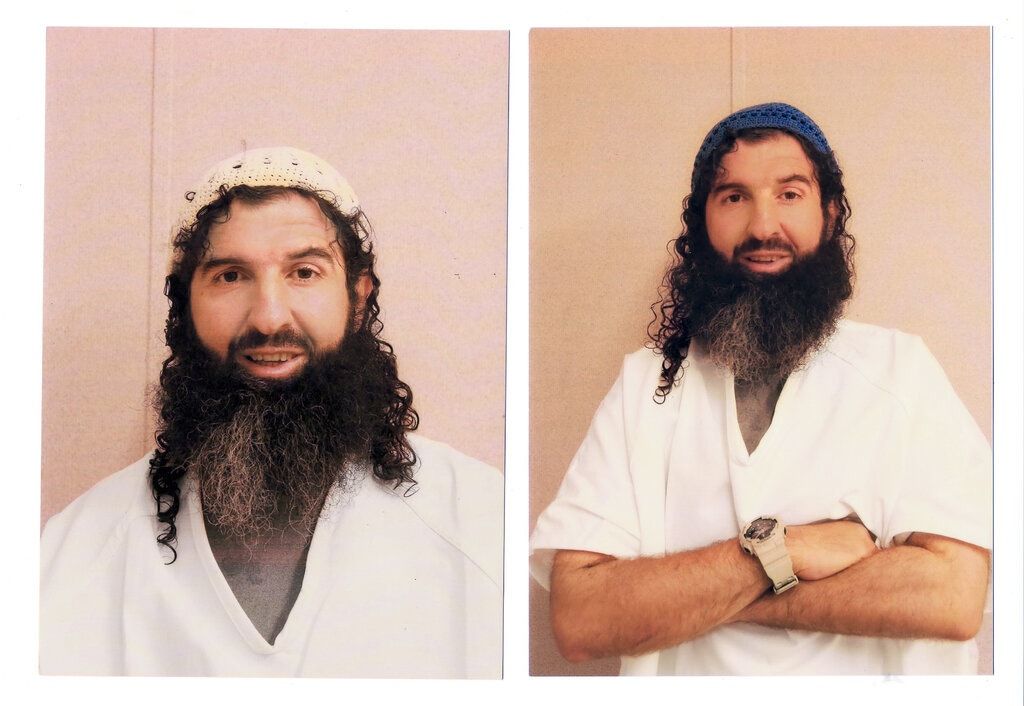

Suspected by the United States of being a jihadist bomb maker, Mr. Barhoumi, 47, was cleared for release in 2016 by a federal panel that reviews the cases of wartime prisoners who face no charges. U.S. diplomats had negotiated his repatriation with assurances from the government in Algeria that it would guard against him becoming a security risk. Only a few final arrangements remained before he would become one of nearly 200 Guantánamo detainees to be released by the Obama administration following the 540 repatriated or resettled by the Bush administration.

But the family’s hopes of a homecoming were dashed by the election of President Trump. His administration halted transfers, dismantled the State Department office that was negotiating them and made clear that it was reversing President Barack Obama’s efforts to close the prison.

The kitchen supplies purchased for Mr. Barhoumi are in storage, members of his family said in a recent interview. A bride still waits, and his 69-year-old mother has put on hold visions of “a normal life with him,” her eldest son.

Mr. Barhoumi, who was brought to Guantánamo in 2002 after being captured in Pakistan, is one of five men among the 40 prisoners at Guantánamo who had been approved for release but did not get out before Mr. Trump took office and changed U.S. policy.

On paper, they remain good to go. And, if Joseph R. Biden Jr. defeats Mr. Trump in the presidential election, the process of reducing the prison population could begin again. Mr. Biden’s campaign said in June that he still wanted to close the prison, and his party platform adopted in the Democratic National Convention pledged to do it.

While Mr. Biden has not said how he would proceed, former Obama administration officials described him as having been fully engaged as vice president in seeking to relocate prisoners and close the detention center. While serving under Mr. Obama, Mr. Biden would raise transfer requests in calls with foreign leaders and bring up the topic in face-to-face meetings, they said.

Lee Wolosky, who was Mr. Obama’s special envoy for arranging Guantánamo transfers in 2015 and 2016, said his office had arrangements to repatriate two of the five cleared men — Mr. Barhoumi and a Moroccan, Abdul Latif Nasser — by the final month of the administration. Then the Trump administration abandoned the effort.

“They have done nothing to further the deals in place when we left office in regard to the Moroccans and the Algerians and to arrange dispositions for the other three,” Mr. Wolosky said. “It takes a lot of work to get these things done.”

The State Department so thoroughly dismantled the office that dealt with resettlement deals, Mr. Wolosky said, that Senegalese authorities telephoned him in 2018, long after he left government service, when a resettlement deal for a Libyan and a Tunisian soured.

If Mr. Trump is re-elected, “It will be a complete disaster,” Mr. Barhoumi’s mother and a younger brother said in succession in a Skype call.

Mr. Barhoumi himself is more upbeat, according to his lawyer. During an Oct. 1 telephone call, Mr. Barhoumi said that “one way or the other he will go home, God willing, even if Trump is re-elected,” said the lawyer, Shayana Kadidal, senior managing attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Mr. Trump pledged during his first campaign to fill up the cells at Guantánamo but has not done so. The prison had 41 detainees when he took office and now has 40. In May 2018, the Defense Department repatriated an admitted Al Qaeda terrorist to serve his war crimes sentence at Saudi Arabia’s rehabilitation center for returning jihadists, a deal made in court in the Obama years.

Only nine of the 40 detainees now at Guantánamo Bay have been charged with or convicted of war crimes. A renewed closure effort could make other uncharged prisoners eligible for transfer, particularly those who might be eligible for medical repatriation.

One candidate could be Mohammed al-Qahtani, 44, a Saudi prisoner who suffered an acute psychotic break attributed to schizophrenia in his homeland even before he was taken to Guantánamo and tortured for two months.

Over Justice Department objections, his lawyers have obtained a court order for an outside medical review to determine if he would receive better care at a psychiatric hospital in Saudi Arabia. But the government could voluntarily send Mr. Qahtani home rather than permit what he is seeking, a visit by an independent medical panel made up of a U.S. Army medical officer and two other doctors from a foreign neutral country.

For now, the five prisoners who have already been cleared for transfer are in limbo, living in the same cellblocks as the other general population prisoners who face no charges.

Mr. Nasser, 55, had a repatriation arrangement like Mr. Barhoumi’s. But time ran out on his transfer to Morocco in the dwindling days of the Obama administration because Congress requires 30 days’ notice in advance of a transfer, and the Pentagon did not forward it in time.

Since then, Mr. Nasser has gained some attention in a six-part podcast narrated by a public radio personality, Latif Nasser, who was struck by the similarity of their names and visited the prisoner’s family in Morocco and toured Guantánamo.

No journalist has been allowed to interview a prisoner there, and Mr. Nasser was no exception. Instead his production posed the question of whether his namesake’s globe trotting, which took him to an Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan in the late 1990s, merited two decades of U.S. military detention following his capture in 2001 by Pakistani security forces.

Another prisoner who is cleared for release with security guarantees is Tofiq al Bihani, 48, a Yemeni from a large Saudi-based family of brothers who joined the jihad. During the Obama years, Saudi Arabia agreed to accept him at its rehabilitation center. In early 2016, he was segregated at the prison with nine other men. The others were taken to a flight to Saudi Arabia. Without explanation, Mr. Bihani was left behind and returned to the prison.

“He is a kind, humorous, fun-loving guy,” said his long-serving lawyer George Clarke, who was furious at the reversal. “We joke with each other. He’s very interested in finding a girlfriend or a wife.”

The cases of the other two cleared prisoners are more complicated. One man is Tunisian, Ridah bin Saleh al Yazidi, 55, who was brought there in January 2002 and was approved for release a decade ago but has shown no interest in leaving. The other is a stateless Rohingyan, Muieen Abd al Sattar, 45.

Before a typical release, a shackled prisoner sits across a table from representatives of a would-be host country or the International Committee of the Red Cross to express a willingness to follow the rules. During the years when the State Department was arranging transfers, neither man would leave his cell for such meetings.

“Two of them had an opportunity to get on an airplane and chose not to go,” Rear Adm. John C. Ring, a former prison commander, remarked in 2018. “So how bad could it be here?”

Other defense and diplomatic officials across the years have described those two prisoners as too profoundly damaged — either mentally ill or accustomed to their institutionalization — to try to seek a way out. That would leave forced repatriation of Mr. Yazidi as one option.

For now, Mr. Barhoumi’s brother and mother are still planning for his return. They anticipate that, like the other 17 Algerians who were repatriated through the years, eight by the Bush administration and nine by the Obama administration, the Algerian government will detain him for questioning before he is released to his family.

Then, “he’ll live his life like a normal citizen so he can make up on the life he’s missed,” said his brother Samir. During a recent call from Guantánamo, Mr. Barhoumi asked his mother whether there was still a willing bride waiting for him. So she checked, and the woman replied: “God willing, when he gets back we’ll make it happen.”