KABUL, Afghanistan - One morning last fall, Zarghoona Salehi stepped down from a van outside Afghanistan's education ministry, a complex of cavernous buildings behind heavily guarded gates. Inside and upstairs, she filled out an application to visit several schools around Kabul. She didn't go into detail about why. That would only lead to delays, or outright refusal.

Zarghoona covers education and health for Pajhwok Afghan News, Afghanistan's largest independent news agency. She attends press conferences and ribbon-cuttings, but she prefers investigating. The government doesn't always like what she writes.

Zarghoona is small but sturdy, like a brief, forceful sentence. At 29, she is an avatar of the new Afghanistan, waking at dawn to pray and cook breakfast for her family before catching a company van to the office. She comes home at night satisfied that her salary helps pay the bills, pretending not to hear her neighbors' whispers: "Look at her. She came in the dark, very late, and her father let her go…"

The news agency where Zarghoona works is only six years old, part of Afghanistan's rapidly expanding media sector, whose growth is a rare post-Taliban success story. Before, Afghans gleaned information from a government-run newspaper and the Taliban's Radio Sharia. Now, 35 TV channels, dozens of radio stations and hundreds of newspapers and magazines compete for their attention.

Zarghoona's sparkly red cell phone is as indispensable to her as the prayer rug where she kneels several times a day. But she is constantly reminded of Afghanistan's powerful attachment to the past. Men like the ones who commandeered her family's home one freezing night when she was a child are still here. They sit in parliament and control ministries. They ride in fancy cars bristling with guns.

"I'm afraid from these people," Zarghoona told me, as an SUV full of them swerved in front of us outside the education ministry. "They have a gun and they can do everything."

In the West, we assume that what comes next will be better than what came before. U.S. military commanders tell Afghans to get off the fence and work for a better future. But many Afghans are suspicious of foreigners and their promises, of everything shiny and new. In their experience, bright things tarnish. The sudden rush of modernity since the U.S. invasion has made some Afghans cling even more tightly to the past. The past may be violent, but at least it is known, at least it belongs to them.

• • •

Zarghoona and her colleagues at Pajhwok (the name means "reflection" or "echo" in Afghanistan's two main languages) spend their days documenting this collision between old and new.

This fall, one reporter wrote about the disastrous effects of new hormones on Afghan weightlifters, who used to bulk up on honey and eggs. Another documented the growing number of men who harass women on streets and buses, an aberration in Afghanistan's deeply modest culture. A reporter visited abandoned buildings, where police and soldiers smoke opium alongside ordinary addicts.

And then there was Zarghoona's story. After a short drive, we pulled up outside one of the best schools in Kabul. Lycee Esteqlal is an old, wealthy institution with tree-shaded grounds and a pristine modern art gallery. Students learn French and Dari, the language of Afghan officialdom.

The topic of Zarghoona's story was the rising violence in Kabul schools. She had heard students were hiding knives and other weapons in their book bags. Some students had even attacked their teachers.

School violence is a sensitive subject in Afghanistan. Respect for elders is paramount here, so the idea that young people would disobey or even attack their teachers strikes at the roots of social order the way it might have 100 years ago in America.

In the principal's office, Zarghoona turned on her recorder, opened her notebook and began asking questions, softballs first. She frowned slightly at the principal's responses, her head scarf slipping back to reveal a flash of dark hair. Rings of sweat formed under her arms, darkening the pink fabric of her blouse.

Afghanistan is a nation of storytellers. But Western-style, fact-based journalism, with its implicit challenge to authority, is a radical act here. Zarghoona had talked to a man whose nephew attended Esteqlal. The boy had carried a knife to school, his uncle said, to protect himself from other students carrying such weapons.

"We haven't seen such things," the principal told her calmly. It was hard to know whether he was telling the truth. Boys were subjected to a cursory check at the gates, he said, but searchers couldn't find everything, and staff couldn't be everywhere at once.

• • •

Zarghoona has learned to control her nerves when questioning powerful people. She wasn't always so brave.

Late one winter night when she was 12, gunmen showed up at her father's house in Kabul. It was 1994, when militia commanders who had expelled the Soviets were fighting each other for control of the capital. "Leave this house," they told Zarghoona's father. They commandeered the place to attack a rival commander.

Three weeks later, her father went back to their house. "How was our home?" Zarghoona asked when he returned. "Everything is burned," her father told her. "We don't have anything now."

The family moved to Pakistan, joining millions of refugees. "Our life completely changed," she said.

The Taliban fell and the family returned to Kabul. Zarghoona got a job writing for a women's weekly, and found that she liked it. After nine months, she joined the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, a British nonprofit that trains journalists in conflict zones and developing countries. That led to a job at Pajhwok.

Zarghoona's father enthusiastically supports her work and ambition. An old man now, he came of age at a time when Kabul was as progressive as any city in Europe. "One day, my father told me, 'I am proud of you. You are a good journalist, and you work in a society for people,' " Zarghoona told me. "Every day he help me and encourage me."

Others are only too willing to impede her.

When she was starting out at Pajhwok, President Hamid Karzai's wife visited a hospital with the wife of the Iranian president. Zarghoona's editor told her to go to the hospital and take the women's pictures. It was the kind of assignment that would raise no hackles in the West, but guards barred her way. Zarghoona's editor called a friend who worked in the hospital and asked her to sneak Zarghoona inside. The guards grabbed her and forced her out. "You are not a good journalist!" they yelled. "Why did you do this?"

"That time I became very sad and crying a lot," Zarghoona told me. Next time, she was better prepared. When a presidential security guard tried to stop her from getting close to high-level speakers at a press conference at the Ministry of Women's Affairs, she threatened to write about him. The fact that he was making trouble for her at an event she had been invited to cover was an indication of how poorly understood journalism remains in Afghanistan.

Her job has put her an uncomfortable half step ahead of the culture in which she lives. Her cousin, a good man with a steady job, recently proposed to her. In Afghanistan, marriage between cousins is common, but Zarghoona has covered the health ministry long enough to know that the children of such unions often suffer birth defects.

"Because of that, I refuse that proposal," Zarghoona told me. "But now he is not getting married and he is waiting for me."

Zarghoona's sister wants her to reconsider.

• • •

Afghan culture is often portrayed as aggressive. In reality it is ornately polite. Rules must be observed. Zarghoona's scandalized neighbors did not confront her; they smiled and whispered disapprovingly. People don't talk openly about social ills like drug use or kids bringing knives to school.

Zarghoona had heard about attacks on a high school teacher and an administrator. The previous year, a student had cut his teacher's face when he failed an exam, then knocked out the principal's tooth when they punished him. A week earlier, another boy had hit the principal in the head with a stone.

More than 20,000 students attend the government-run school. The classrooms are plain stone, without glass in the windows or proper doors. On the day we visited, some girls were studying in an empty shipping container. Others sat at desks on a windswept lawn, their makeshift classrooms marked off by bed sheets hung from ropes.

Zarghoona met with the principal of the boys' school, the one who had been attacked. He was an older man in a shirt and tie, with a shiny bald head and a white beard. Zarghoona asked whether boys were bringing box cutters and other weapons to school.

The principal said that some did. It was impossible to control so many students, he said, and parents were little help. Student "scouts" — the Afghan version of hall monitors — were assigned to the main gates of the school every day, but there were only 10 of them, and they couldn't catch everyone.

Like other administrators, the principal blamed school violence on Afghanistan's 30 years of war. "These boys saw fighting, guns and all of this violence," Zarghoona told me later. "They learned, and they do these things in the school also."

But she noted this, too: Indian and Western movies about gangsters and thugs are now widely available on Afghan TV. Kids were watching these films, Zarghoona told me, and "acting like superstars."

When Zarghoona was done interviewing the principal, I tried to ask him about the boy who had hit him with a stone. Zarghoona translated my request. She and the principal spoke quickly in Dari, and then Zarghoona turned to me: "He doesn't want."

I asked Zarghoona about it later. The recent attack was such an affront to Afghan culture that he didn't want anyone outside the country to know about it. "We are ashamed of these things," she explained.

The principal didn't know that Zarghoona's story would be published in English for foreigners like me to read. But the English translation of the story also didn't explain that it contained information that foreigners in Afghanistan routinely miss.

• • •

We went back to Esteqlal school so Zarghoona could talk to some students. Guards manning a checkpoint near the presidential palace stopped us. Zarghoona showed them her press card. The men asked us to wait, but Zarghoona, flushed with anger, told the driver to turn around.

"In Afghanistan, it is simple," she said. "If someone has a gun — has power — they always do like this."

She predicted that she would be dead before the country made the kind of progress she and her colleagues hoped for.

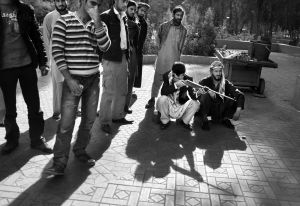

By now, we had reached the school. Zarghoona strode down the sidewalk, stopping to interview some small boys on their way to class. Did they know anyone who brought knives to school?

"No," the boys chorused.

A security guard working for the school scolded Zarghoona loudly. This was a public sidewalk, but in Afghanistan that didn't matter.

"Okay, we're going," Zarghoona told him. We started walking, the little boys running alongside.

Zarghoona stared out the window on the way back to the office. On days like this, she didn't feel strong or brave. She felt like an Afghan woman, five feet tall in heels, pushing against centuries.

• • •

Zarghoona wrote her story. Students and parents told her that weapons were growing more common in schools, but the education ministry said that school violence had fallen. She quoted both sides.

On my last day in Kabul, breaking news electrified the Pajhwok newsroom. A fight had erupted at a school. One student was dead, another badly wounded. Baseer, the crime reporter, got on the phone. Two gangs of students had fought. One group came from the southern province of Helmand, the other from Paktika in the east.

I thought of the gang wars in American cities. Afghanistan has been asked to undertake a radical form of time travel that is pulling it apart. This is not the first time. Every few decades, the cities surge forward, the villages dig in, and the country quietly goes to war with itself.

Americans barely have time to understand U.S. policy in this faraway place, where their sons and daughters are dying, let alone these small internal arguments. But big things are made up of small things. Afghan reporters are documenting these small things, one at a time.