Every Friday, Brazil’s Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL) holds a public forum in Praça Mário Lago, a public square just five minutes away from the Câmara Municipal in Rio de Janeiro’s Cinelândia district. Members of the public are invited to ask questions about the week’s events and they hold members of the party accountable for their actions.

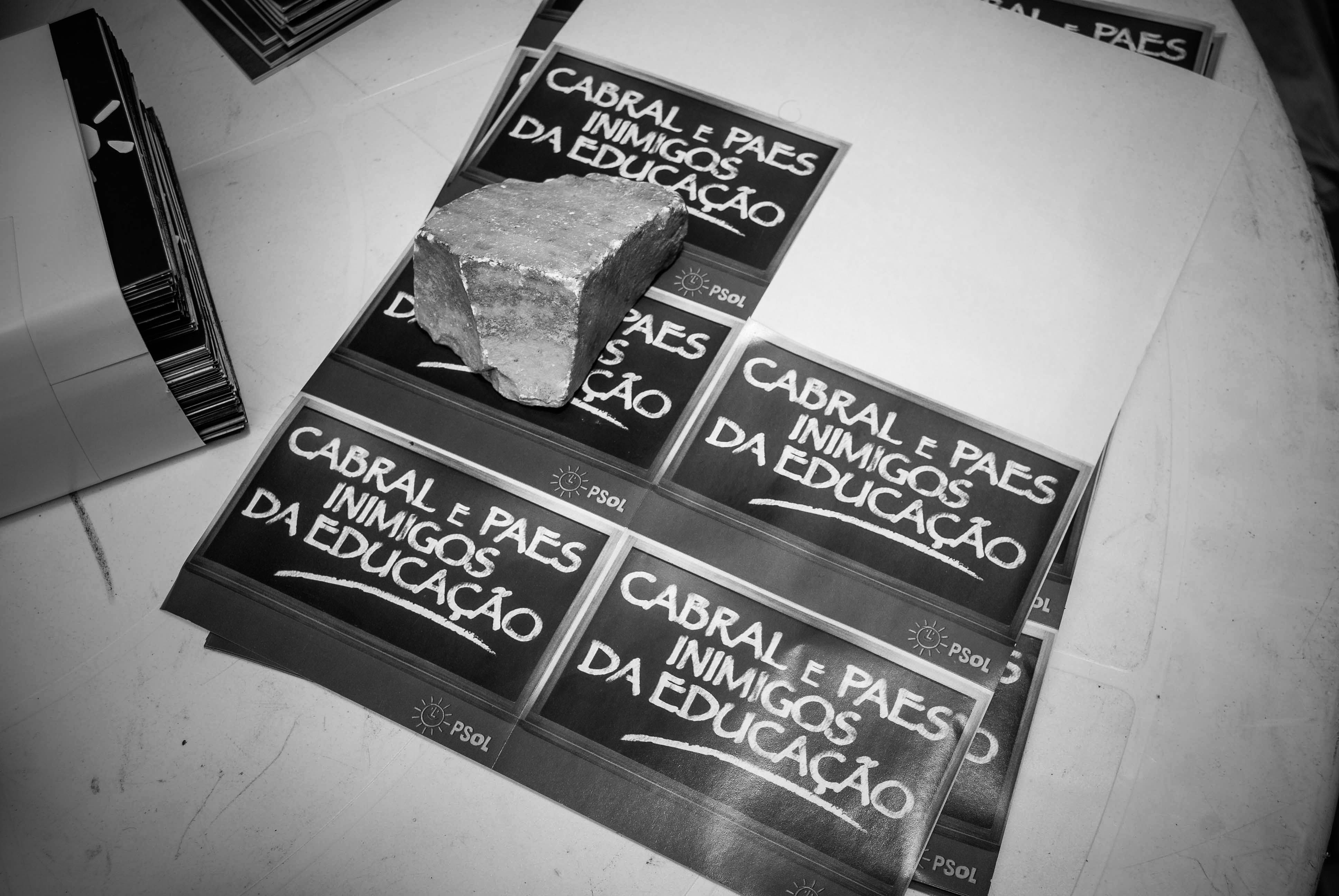

Founded in 2004, PSOL is a Brazilian political party known for its role in mobilizing support for anti-capitalist protests as well as for education and public health reform. Members also support a number of human rights-focused campaigns and are currently monitoring the government’s “street cleaning” exercises.

Renato Cinco’s main campaign focuses on the legalization of drugs in Brazil and, in the last few years, his work has centered on the moral panic around the “war on drugs,” which he believes is being used as an instrument for criminalizing the poor.

Cinco and his advisors are closely monitoring a policy begun in May 2011 by the social work department, which involves the mandatory detainment of children and adolescents living on the streets for the purpose of drug rehabilitation. According to Cinco, teenagers and children are collected from the streets in vans and then taken to centers on the outskirts of the city where they receive treatment for their drug habit.

However, because some of these centers are private institutions, contracted by the government, they are not open to the public. Cinco suspects that the centers are financed through religious institutions and used to “brainwash” young people. The lack of transparency makes it difficult to tell exactly what goes on in inside the walls of these centers.

Cinco also worries that the health needs of those interned are not being met; human rights organizations and medical professionals warn that the complete withdrawal from drugs can be extremely dangerous for those with serious addiction.

In January 2013, the program of compulsory rehabilitation was extended to drug-using adults who live on the streets, but it did not continue past February due to pressure from civil society and arguments that the policy contravened constitutional law.

However, the removal of the non-drug using adult street population has not stopped. Homeless people have been transported to centers on the outskirts of the city--simply for being homeless and an “eyesore”-- since the 1990s. It’s not compulsory for people to stay at the centers, as it is for drug-using adolescents and children, but often they have no money or way of getting back other than walking. If they do manage to make it back to the city, Cinco tells me, they risk being picked up and detained again. Official data from the central government suggests that a homeless person may be collected 53 times, on average, in the course of his or her life on the street.