The arrests of Afghan journalists this past week for allegedly enabling the Taliban propaganda machine reminded me how little NATO forces understand about journalism. Perhaps they shouldn't be expected to understand. They're soldiers after all, not reporters or editors. But increasingly, international forces in Afghanistan are waging an information war, one the Taliban appears to be winning. Arresting Afghan reporters instead of the Taliban fighters and spokespeople who talk to them isn't just bad for journalism. It plays right into the insurgents' hands.

Last winter, I spent three weeks embedded with a U.S. Army brigade in eastern Afghanistan that prided itself on its media strategy. I made many requests of the brigade's public affairs officer for interviews, transport and other logistical help during that time, and after a while, we grew chatty. One day, when I was snowed in at a mountain base, he emailed me a link to a TV package produced by France 24, with a note: "Here you go, Taliban lover!!" The 26-minute account of a Taliban attack on an Afghan police checkpoint in Wardak, a province just south of Kabul that has slipped from government control, features lingering shots of Taliban fighters cleaning their weapons and riding around the countryside in pickup trucks as they prepare their assault. The camera crew followed the insurgents into battle and accompanied them back to the police post a day later to assess the damage. A précis on the France 24 web site calls the attack "apparently a success" for the Taliban. I told the public affairs officer that although the French TV piece was heavy on hagiography, the journalists who produced it were right to try to tell the Taliban's story. Reporting on the insurgency has become extremely difficult for international reporters in Afghanistan because so much of the country is unsafe for foreigners. In most cases, Afghan reporters are the only ones who can access areas under insurgent control. The rest of us rely heavily on their accounts. You should be grateful to France 24, I told the public affairs officer. Watch the program and learn something about the way your enemy thinks.

He vigorously disagreed, arguing that the French reporters should be arrested for treason because they were stoking the reputation of a group that had shed the blood of their own nation's forces and that of Afghans whom the French and other NATO troops support. I silently considered the many hagiographic accounts of American activities in Afghanistan that I'd watched and read over the years, often produced by American journalists who never left the U.S. military bubble. Why were those acceptable, while the French TV piece wasn't? I was no Taliban lover, but I was frustrated with NATO media officers who viewed stories as either "good" or "bad" for their interests, and decided accordingly whether to encourage or try to quash them. This was propaganda, too, and no better for hewing to the coalition line. The public affairs officer rightly pointed out that the Taliban takes advantage of Afghanistan's inaccessibility and danger to spread inaccurate accounts of its successes and NATO's failures. It's almost impossible to independently verify competing claims about battles, say, or civilian casualties without days of sometimes life-threatening travel and investigation, so reporters end up quoting both sides in an attempt at fairness that does little to establish what really happened. To settle the argument, I asked him to find out what his brigade commander, a bright, seasoned officer, thought of the French TV piece. A couple of days later, I heard back. The commander also believed that the France 24 journalists "should be arrested," the public affairs officer emailed me, adding: "Victory is mine."

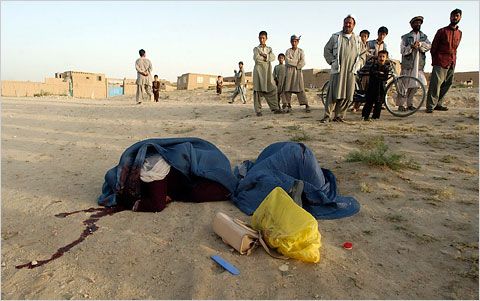

But what kind of victory would it be? Early Monday morning, international troops arrested Rahmatullah Nekzad, a freelancer for the Associated Press and Al Jazeera, at his home in Ghazni. They arrested Mohammad Nader, a staff correspondent for Al Jazeera, in a similar raid early Wednesday in Kandahar. Afghan journalists, local officials and international media organizations immediately called for the men's release, along with radio and TV reporter Hojatullah Mujaddedi, who was arrested Saturday by Afghan intelligence agents while covering the parliamentary election in the central province of Kapisa. A NATO press release called Nekzad and Nader "reported" Afghan journalists and said that Afghan and coalition forces had intelligence linking them to insurgent propaganda networks. "The insurgents use propaganda, often delivered through news organizations as a way to influence and in many cases intimidate the Afghan population," the statement said. "Coalition and Afghan forces have a responsibility to interdict the activities of these insurgent propaganda networks." Nekzad has been through this before. In 2008, Afghan authorities detained and questioned him for two days after he witnessed a Taliban execution of two women and photographed its aftermath (he later said he had been summoned to attend a trial and didn't realize anyone would be executed, according to the Associated Press). A NATO press release issued the day after his arrest and blandly titled "Update on Key Developments Across Eastern Afghanistan," noted that Afghan and coalition forces captured "a suspected Taliban media and propaganda facilitator, who participated in filming election attacks" in Ghazni, but did not give Nekzad's name or identify him as a journalist. International forces found grenades and ammunition in his home, but that isn't unusual in Afghanistan. Meanwhile, Al Jazeera, which was famously a target of U.S. ire and precision-guided bombs in Iraq, posted footage on its web site of Nekzad's ransacked house and his young daughter speaking tremulously about the soldiers who beat her father and carried him away into the night.

By Friday evening, all three journalists had been released, but the damage was done. NATO issued another lengthy statement, saying that said Nader and Nekzad both "admitted having routine contact with the Taliban" – something the men probably would have told coalition forces over a cup of tea had anyone bothered to ask. "No guilt or innocence is presumed by our activities," said ISAF communications director Rear Admiral Gregory Smith, hurriedly backpedaling. Smith met Friday with Samer Allawi, Al Jazeera's Kabul bureau chief, who, according to the network "was recently threatened and pressured to change the editorial line." In an unusual burst of sensitivity, NATO pledged to "ensure…that journalists are treated with respect as they endure the challenge of reporting in an often dangerous and complex environment."

How does any of this amount to a NATO victory? Why not detain the Taliban's most effective spokespeople if the goal is to stop them from talking? Afghan reporters have enough problems trying to get their stories right amid pressure from all kinds of power brokers in a place where, under the best circumstances, facts are extraordinarily hard to pin down. Arresting them doesn't help. If NATO wants to improve the quality and fairness of media coverage here, it might consider increasing support for programs aimed at building skills and professionalism in the Afghan press. This is slower than pouring tens of thousands of dollars into an Afghan-run TV station with the tacit understanding that it will broadcast pro-coalition programs, as the brigade I visited in eastern Afghanistan last winter chose to do. But in the long run, training Afghan journalists will prove far more effective and sustainable than buying them or throwing them in jail. As I told that brigade public affairs officer, reporters don't like being lied to. If a journalist learns that a Taliban source has misled him about the number of civilians killed in a NATO air strike or coalition vehicles destroyed in an ambush, he will be far less likely to listen to that source in the future. And if what the Taliban says is true, NATO and the rest of us might learn more by listening than by switching off the set.

Image for this post by Rahmatullah Nekzad/Associated Press. Afghanistan, 2008. Two Afghan women accused of prostitution were executed by the Taliban in 2008. The journalist who documented the event, Rahmatullah Nekzad, was detained this week for allegedly enabling the Taliban propaganda machine.