The Deepwater Horizon accident reminds us that oil drilling is dirty business.

Ecuadorans know this fact. They’ve lived off, and with, oil for more than three decades. For many Ecuadorans, oil promised riches but delivered ruin. Along with great wealth, for a few, it stimulated political vice and the noxious excretions.

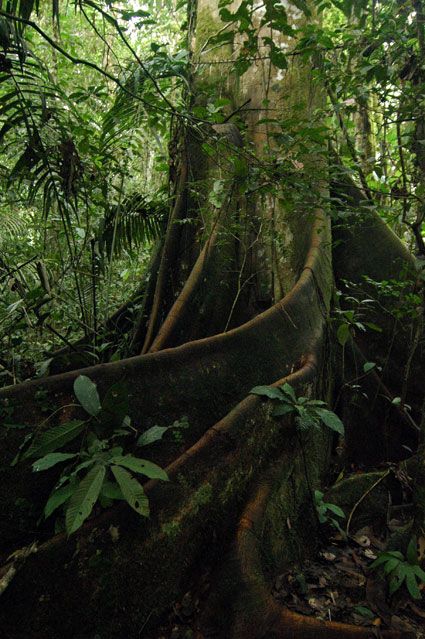

Outsiders rarely glimpse the dark side of oil. But I traveled recently to Ecuador’s Amazonian lowlands, driving through cleared rain forest, flying to a bumpy landing strip, and squatting on the damp floor of a dugout canoe.

My local friends pointed to the obvious evidence that this small nation has paid exorbitantly for its membership among oil-producing nations. They also showed me evidence of hope that Ecuadorans might tame their oil demon.

I learned in school that Ecuador straddles both the Equator and the Andes, the Pacific to the west and the Amazon Basin to the east. Barely the size of Nevada, the South American nation is a gilded jewelry box of treasures.

Darwin nailed down his theory of natural selection in Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands, a menagerie of unusual animals.

The volcano Cotopaxi, the place on our bulging Earth farthest from the core, is decorated with a glacial shroud shining round the summit. About once a decade the 20,000-foot-high cone burps lava and gas.

A few acres of the virgin forest in Ecuador’s Amazon headwaters, on the eastern slopes of the Andes, nurtures more types of trees, frogs and toads, and bats than all of the continental United States and Canada.

But since Ecuador started pumping oil, the Amazon lowlands sparkle less brightly.