In the realm of the video news reporter, if you don't have it on tape, it didn't happen. OK, it's not always so extreme, you can narrate the occurrence of an event and use vaguely relevant or generic images -- say a compression shot of people walking on the street -- to cover that narration. But if the element is highly specific, then no video equals no event.

Many, many times on a shoot we'll glimpse an incredible image out the window of our car, but know immediately that by the time we stop, get the camera set up and rolling, the moment will be gone. And often, all it takes is for the camera itself to appear and be seen, to irrevocably change the moment.

So, very little can be as heartbreaking as when everything appears to be just right for filming: the event is unfolding, the camera is rolling, the subjects are doing their thing, you're getting great material… and then you later learn that due to some rare technical malfunction, the wonderful images you thought you'd recorded, the event you thought you'd documented, was gone for good (or for your purposes, never existed)!

This happens rarely, but we sadly had such a circumstance on our recent shoot in Haiti. We are covering what is being heralded as "Haiti's moment of hope", the confluence of security and investment interest that has people optimistic about the Caribbean nation for the first time in years. And last month, while Americans were lining up outside shopping malls all across the US, waiting for those Black Friday sales to begin, our team was heading out into the Haitian countryside to document a vital aspect to this nascent hope: agricultural development.

Most of the investment interest in Haiti has centered around either the garment industry -- the assembly of tee shirts and simply constructed clothing like medical scrubs -- or tourism. We'd already covered the visit of a South Korean delegation looking to set up garment assembly facilities in Port-au-Prince, and we'd filmed a training program to get Haitians up to speed on sewing machines to staff those factories. We were going to miss the big tourism event by a week (the arrival of the world's biggest ocean liner, the Oasis of the Seas, to a dock in Northern Haiti) but we knew we could cover the tourism angle through some footage of President Clinton's visit to the country the previous month. But the agriculture part of the story was a big one, and we worked hard to find the right program to film that would make the points of 1) the need for jobs to be developed outside city limits and 2) the great potential of Haiti's troubled but naturally-blessed rural areas.

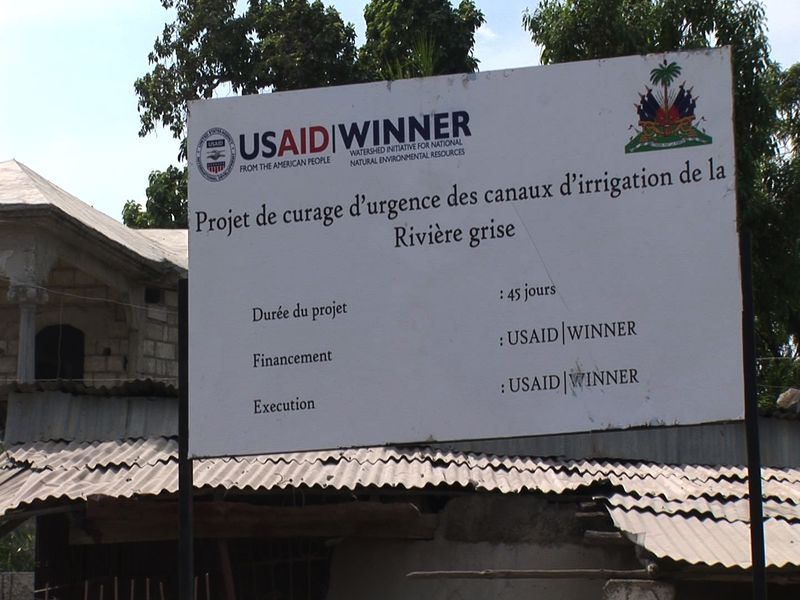

And so we set out that morning with Maxwell Marcelin, the local representative of the USAID-funded WINNER Program. WINNER stands for "Watershed Initiative for National Natural Environmental Resources"; a fancy name to make a good acronym, perhaps, but upon visiting the program, it became clear that this was indeed one that could have some real impact on the lives of local residents.

The WINNER program is working in the Cul de Sac Watershed about an hour outside Port-au-Prince, to channel waters from the flood plains, in order to redirect them for farming, and to dredge and put back into use a series of canals built in the 1930s but buried in mud for the last several decades. (There is a second similar project underway in the Gonaives Watershed region of the country.)

The floodplains were an awesome sight: miles of windswept boulders with an occasional trickle of water winding through, which one could easily imagine turning into a raging flood after a decent rain. Bulldozers were building some restraining walls there to redirect such floodwaters towards the canal system (and away from local homes, which are regularly washed away in Haiti's periodic disasters).

But it was the scene around the bend, as the canal system became revealed, that was the best video of all: a group of about 20 local farmers, each with a shovel, each helping to dredge the canal that would soon feed their crops. They get paid for their shoveling work, but they are also part of a collective that will one day soon both farm the land and actually run the maintenance on the canal – a way of keeping the farmers invested in the success of the project and creating sustainable impact. The original canal had been covered in almost 18 feet of dirt and jungle growth, deep enough to bury some bridges that were now once again being revealed. Once the canal is fully dredged, the walls will be cemented to keep the nearby fast-growing banana plants from once again claiming the waterways.

One of the farmers, Augustin Orilus, said he thought he was about 80 years old; he was too old to do the digging, but was intently watching the progress, a sugar-cane cutting machete in his hand. Orilus told us that this was a life-changing moment for him and his neighbors: that Haiti's land had for years been "unlivable" but that now a potential for sweet potatoes, beans and other late season produce might help them all scrape together a better existence. WINNER spokesman Maxwell Marcelin says the program hopes to double the farmers' outputs within the year.

If all television could be so rich with visuals, quotes and overall optimism! The entire crew agreed that the Orilus interview had been one of the most heartfelt and moving we'd filmed anywhere.

But then, the sobering reality upon return to New York that of the 17 hours of footage shot during our Haiti trip, the single tape we shot with the WINNER program was irreparably damaged, perhaps by a speck of dust from the dry flood plain that had slipped between the recording heads of the camera and the tape that we thought was capturing our images. Even Sony's brilliant technicians at their special videotape facility in Dothan, Alabama couldn't save us. As of now, the tape sits on our shelf, a reminder of our day in Haiti's countryside – one that we thought would be a big part of our overall story but that now is only a painful reminder of the occasional difficulties of television production.

For more on this reporting project, and to see the video we DID manage to record, visit the Fragile States Gateway.