This slideshow was also published in The Atlantic.

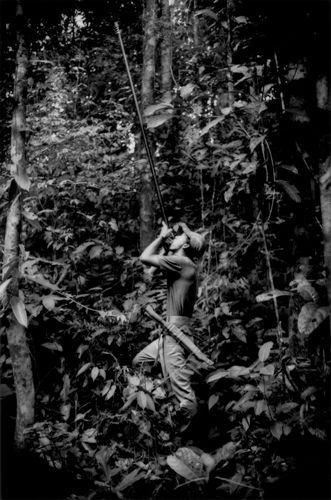

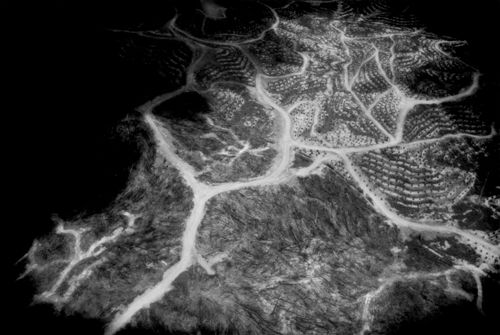

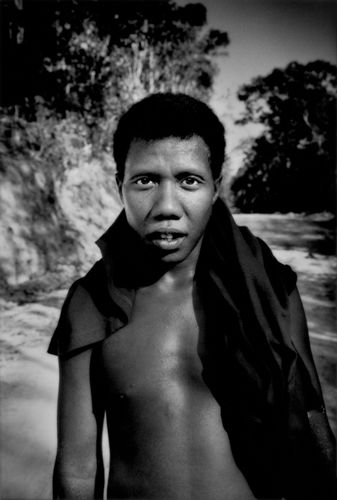

Biofuel in Malaysia is neither “green” nor an alternative to fossil fuels. Meanwhile, two indigenous “little peoples”--little in stature, little in number and of little importance in the eyes of the government--are in the process of losing or have already lost their rainforest homelands to logging and ultimately oil palm plantations. Malaysia is now the world’s second largest producer of palm oil after its larger neighbor, Indonesia.

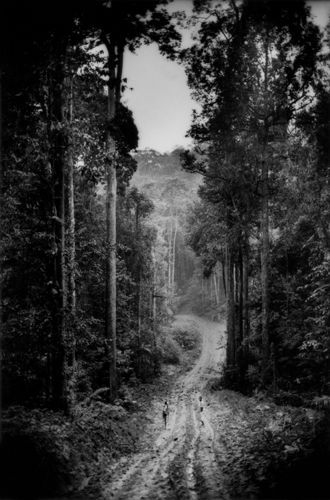

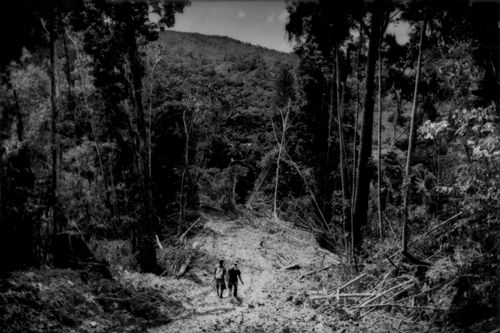

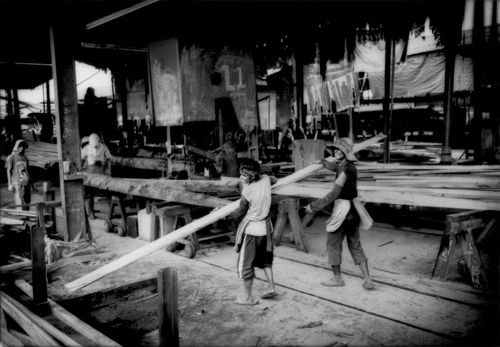

In the most common progression, logging companies obtain logging concessions from state governments with little or no resistance from indigenous peoples. This is because the indigenous people have limited land rights, and because most neither read nor write Malay, the official language in Malaysia. In the past, communities were often unaware that a concession to log their ancestral land had been filed until one day heavy logging equipment would turn up and start felling the forest. Loggers “selectively” cut down the most valuable species of trees. This, they claim, is sustainable logging. It is not. Opening up logging roads and dragging out felled trees devastates the thin tropical top soil. Usually, after the best trees have been removed, the logging company will return for a second or even third pass to grab less valuable tree species, leaving behind a ravaged, unproductive forest. The soil, by this point, has mostly washed away in the torrential tropical rains while forest animals have left or have died of starvation. The rivers have become so full of silt as to be undrinkable without major filtration and are devoid of fish. Finally, oil palm plantations, often subsidiaries of the same large corporations as the logging companies, are introduced to the exhausted land, sealing its fate.