Editor’s note: Read all the stories about how county law enforcement officers in Maine escape accountability here. The series was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Off and on for about a year, the Bangor Daily News’ Maine Focus team investigated misconduct and discipline at sheriff’s offices across the state. This investigation produced seven stories, which we’ve linked to below, along with key takeaways from each.

A Maine Sheriff Resigned After Sexting His Officers. The Full Story Is Even Darker.

— Former Oxford County Sheriff Wayne Gallant resigned in December 2017 after an internal investigation found he had sent graphic sexual photos to several people, including employees. But unlike police chiefs, who report to local government officials, sheriffs are elected, and county commissioners have no power to punish them. That meant commissioners couldn’t even put Gallant on leave while both they and the FBI investigated him, giving him time to allegedly destroy erotic images on his devices.

— Oxford County paid out more than $170,000 in investigation costs and settlement fees to two former employees who alleged Gallant sexually harassed them. The settlements represented some of the highest payouts to county employees in Maine in recent years, and show how counties have no real control over sheriffs but are financially responsible for them.

— The body that certifies law enforcement officers in Maine didn’t look into pulling Gallant’s certification to be a police officer because allegations of sexual harassment do not fall under its purview. Some officers believe this should change.

In Trove of Officer Misconduct Records, Maine Sheriffs Hide the Worst Offenses

— In an unprecedented review of nearly 500 discipline records from sheriff’s offices across the state, the BDN found that a third of the records documenting serious discipline didn’t contain enough information or detail to understand what misconduct had transpired, leaving the public in the dark about what really happened, whether discipline is equitable across offices and violations, and whether elected sheriffs are holding their staff accountable.

— Counties had drastically different numbers of discipline records even when adjusting for the number of officers employed, demonstrating a lack of standardization between sheriff’s offices.

— Two counties — Washington and Somerset — didn’t provide any discipline records for officers, a dearth of data experts found troubling.

A Searchable Database of 5 Years of Punishments for County Officers in Maine

— The database of discipline records from sheriff’s offices details nearly 100 serious offenses — resulting in suspensions, demotions and terminations — as well as incidents that prompted officers to resign in lieu of discipline.

— The database allows the public to see which sheriffs are clearly documenting misbehavior and which are not. Cumberland County, for example, produced 23 records of serious discipline, and only one record was incomplete. Knox County, however, provided 13 records of serious discipline, and eight were incomplete.

The Maine Sheriffs That Destroy Discipline Records

— When a sheriff’s office disciplines an officer, the office creates a record of that discipline that goes into the officer’s personnel file. But, depending on the county, that record could stay in the file for decades, or it could be removed in a matter of months, complicating efforts to track misbehavior and resulting in varied treatment of officers.

— The differences between how and if counties maintain discipline records stem from the counties’ contracts with their unionized officers.

The Sheriff Fired Him. Then the Police Chief Fired Him. Each Time He Kept His License as a Cop.

— The Maine Criminal Justice Academy has the power to decertify officers for misconduct, but its authority is mostly limited to punishing behavior that’s considered a crime. As a result, it is powerless against other ethical transgressions such as depravity or violations of the Maine Human Rights Act.

— One former officer, Scott Francis, avoided decertification twice in three years, in 2010 and 2013, after local district attorneys declined to prosecute him for domestic violence. However, his sheriff, and then his police chief, still fired him. Meanwhile, his ex-wife said in civil court filings that he harassed and abused her, prompting a judge in 2012 to call him “about as openly hostile and disrespectful as any spouse I’ve seen on the bench in 19 years.” The academy eventually decertified him in 2016 after he was convicted of theft, tax evasion and perjury.

— Francis might have been disciplined sooner if he patrolled in another state where officials can decertify officers for violations of moral turpitude. As part of a review of hundreds of discipline records from 2015 to 2020, the BDN identified 21 cases where, if the officers had worked in another state, officials there might have had the authority to review their certification.

A Secret Settlement Hid an Officer’s Misconduct. Outside Maine, It Would Have Been Different.

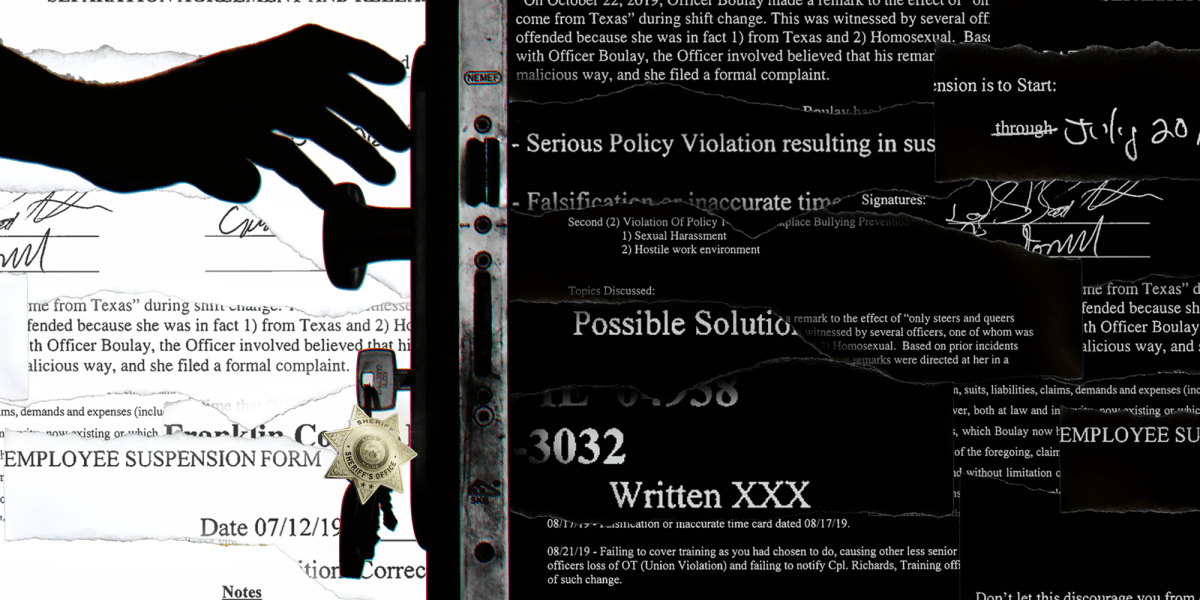

— Franklin County disciplined a corrections officer named Casey Boulay six times for various infractions and eventually placed him on leave for incidents related to sexual harassment and creating a hostile work environment. But instead of terminating Boulay, the county cut him a deal: In exchange for his resignation, it would agree not to tell future employers or Maine’s police overseer about his misconduct.

— Settlement agreements like these can make it harder for law enforcement agencies to gain information about job candidates’ past performance as police and corrections officers. It means future employers could hire someone without learning the full scope of the person’s history.

— Some states, however, now require past agencies to release details about officers who used to work for them, regardless of whether officers signed a confidential settlement agreement, and have given agencies legal immunity to get and share information.

How We Investigated Wrongdoing at Sheriff’s Offices in Maine

— Here’s a behind-the-scenes look.