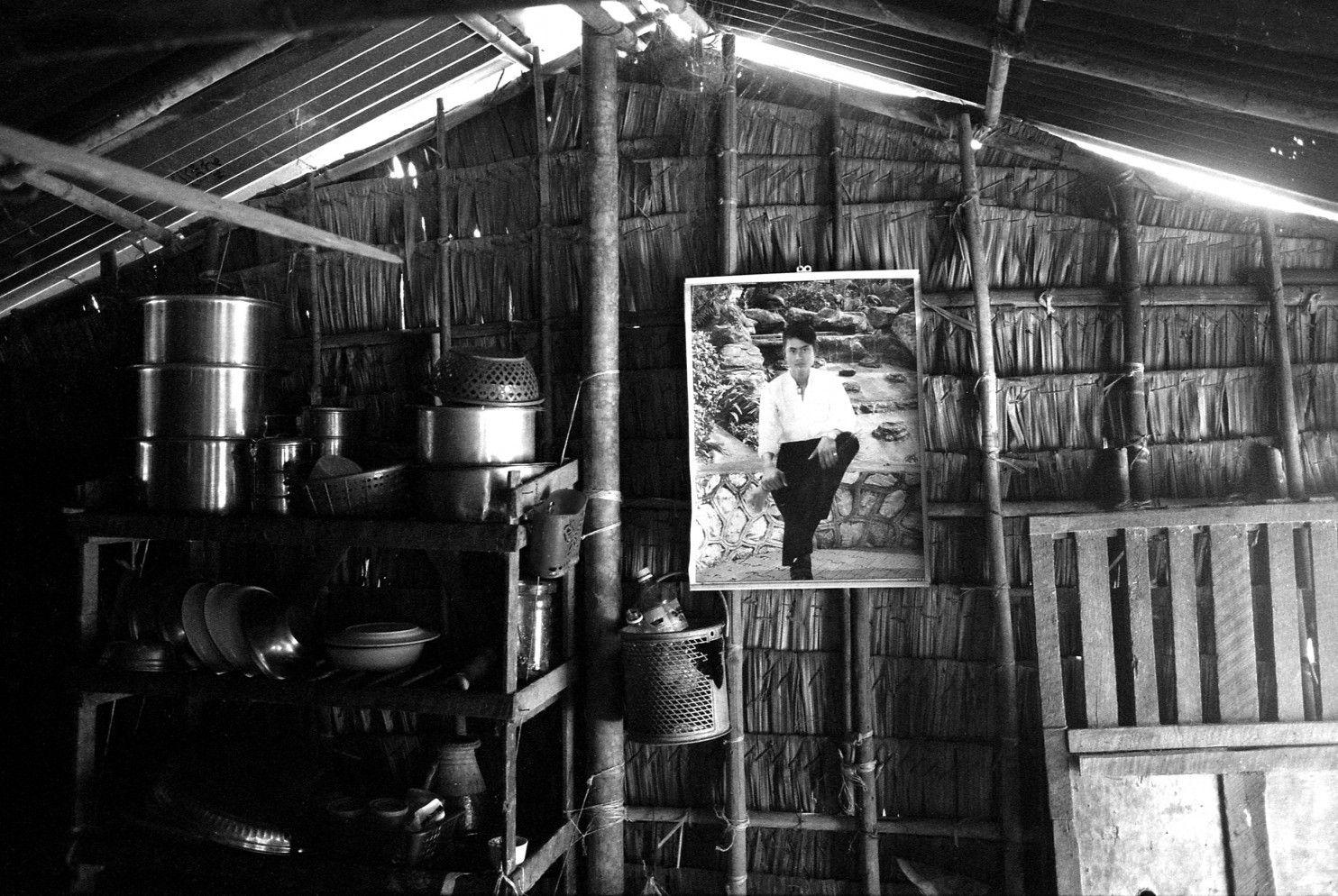

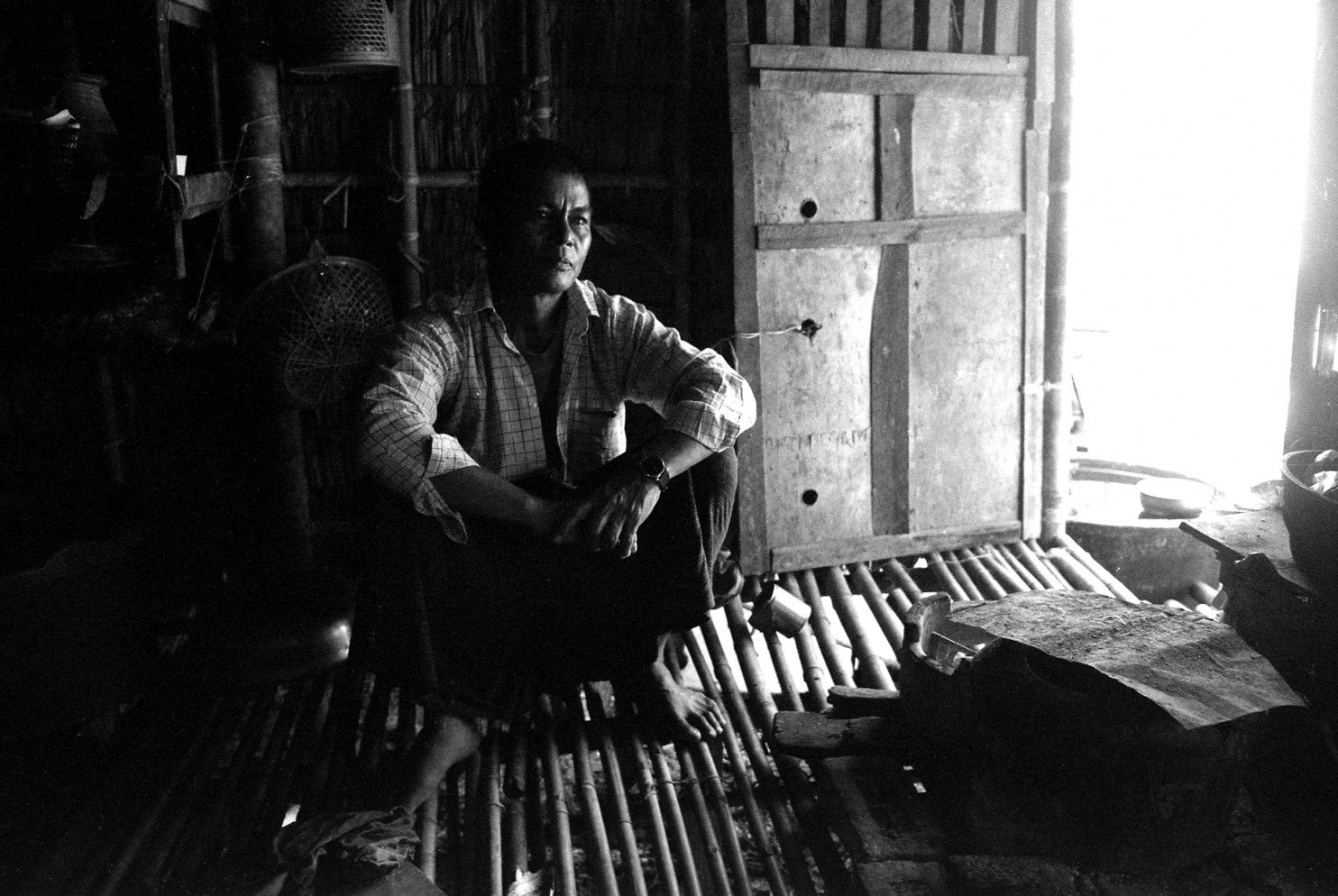

Thein Myint’s bamboo hut is filled with villagers looking for help: Mothers, fathers, sons and daughters of the missing. Their boys were kidnapped by the Burmese Army and recruited for active service. In the 20 square foot shack in the shanty town of Dine Su, on the edge of the Yangon River in the country also known as Myanmar, people crowd into the small space filling every available crevice. The men spit betel juice though the cracks in the worn boards and the women fan each other to keep cool. Younger children peek in from outside, their fingers clawing through the steel mesh in the glassless window.

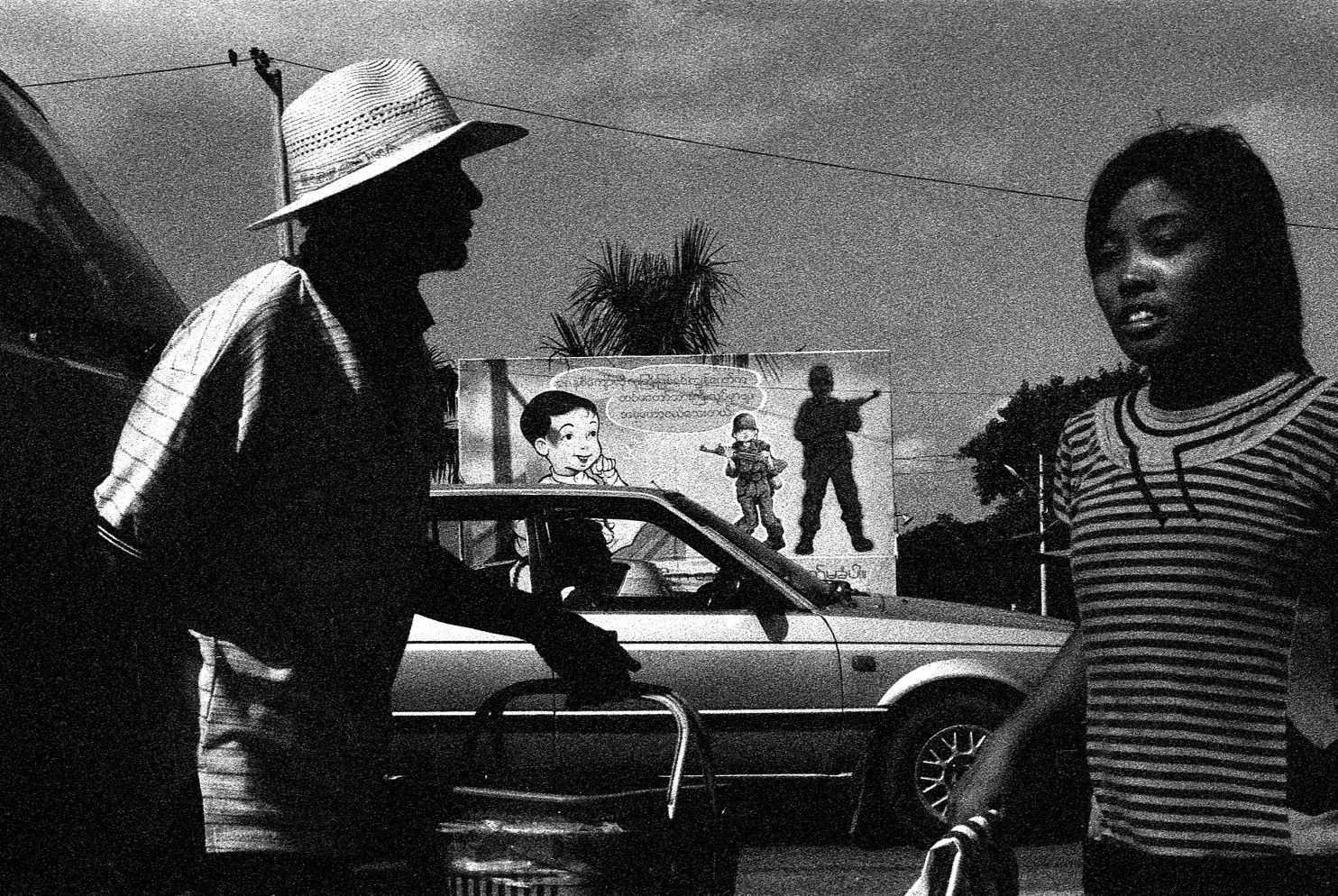

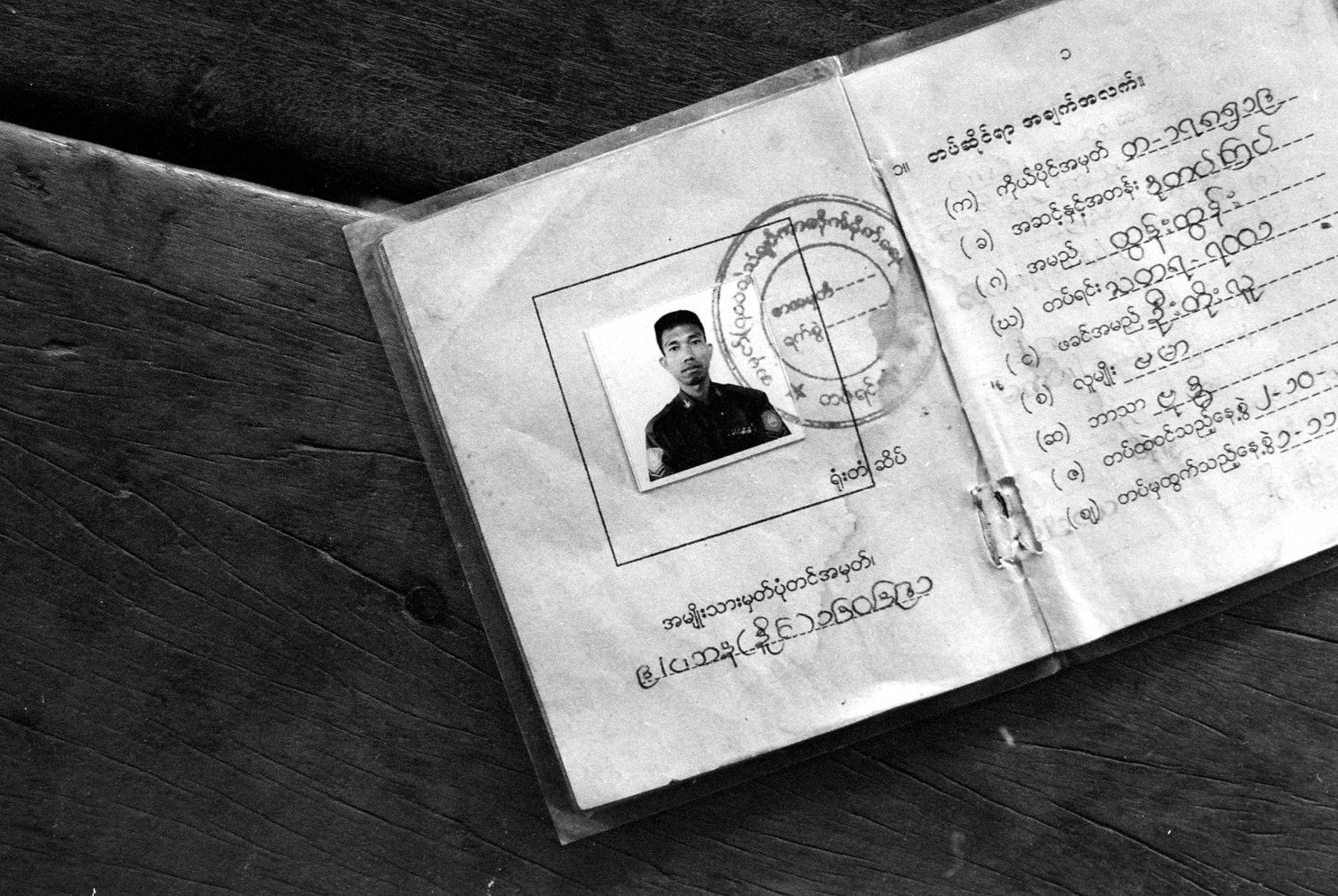

Since the violent crushing of student protests in 1988, the army’s need for rapid expansion has encouraged the forced recruitment of boys–many as young as 11–to fulfill quotas. Kidnapping, beatings, even drugging are common tactics used to lure boys off the streets and on to the front lines, to sweep for mines and fight. An exact number of missing children is hard to ascertain because of speculated identity forgery committed within the army.

Photojournalist Spike Johnson has documented humanitarian aid issues throughout Asia, Europe, and the United States. In 2014, the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting funded Spike to produce a body of work on the Burmese Army’s release of its forcibly recruited child soldiers.

The military government stepped down in 2011, and the new government has undertaken reforms, although the process has been contentious. For the past few years, the army been releasing the boy soldiers as part of an agreement with the United Nations. As recently as December 2014, the army released 80 child soldiers from active service, bringing the total of freed children to 845 since 2007. There has been steady pressure on the army and militias to fall in line with ASEAN human rights recommendations, and International Labour Organization conventions.

However, although Burma is a member of the Convention of the Rights of the Child, the use and recruitment of child soldiers is still commonplace. Slowly though, soldiers who were forcibly recruited as children are returning to their villages, to their families who have long thought them dead.

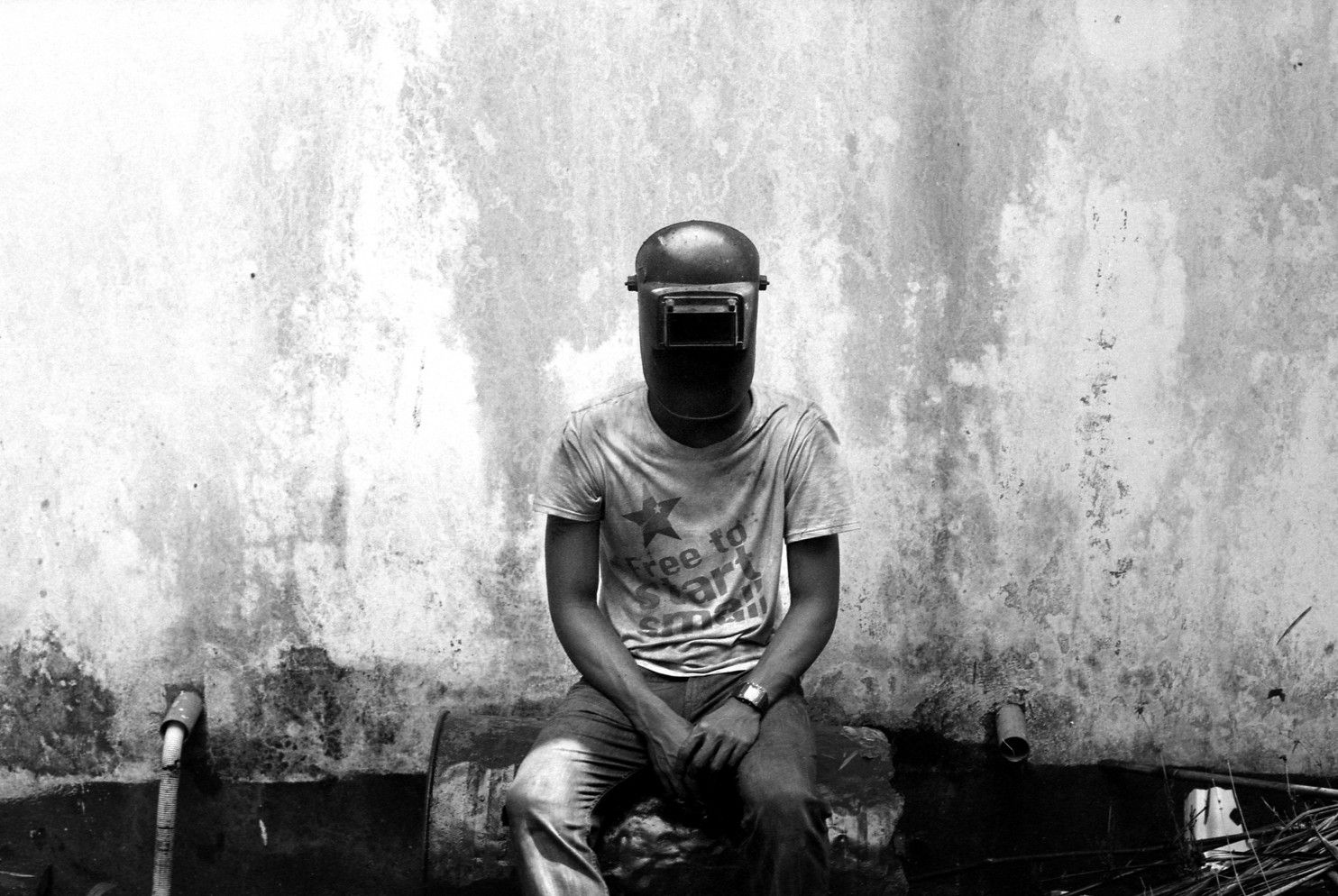

![At 15, Arkar Win (center) was lured away from his village by a man offering him driving lessons. He was drugged and awoke in an army base. “I was told I’d been sold to the [Burmese] Army for $80,” he said. Now 21, he’s free and working in a fish yard on the River Yangon. He earns $2 per day, and commutes an hour up the river to his village, Dine Su. Image by Spike Johnson. Myanmar (Burma), 2014.](https://legacy.pulitzercenter.org/sites/default/files/styles/node_images_768x510/public/03-19-15/imrs-5.php_.jpg?itok=ZQqBHE2d)

![Akar Min shows the pastry used to conceal sedatives by a broker that delivered him to the Burmese Army. “After I ate this, I couldn’t stay awake,” he said. “I woke half way though the next day. I was told I’d been sold to the [Burmese] Army for $80.” Image by Spike Johnson. Myanmar (Burma), 2014.](https://legacy.pulitzercenter.org/sites/default/files/styles/node_images_768x510/public/03-19-15/imrs-11.php_.jpg?itok=FXye_cek)