Today was a fiasco.

Having cooled our heels all morning waiting for press accreditation badges, Carolyn and I finally hit the road. We are both eager to check out the isolated farming communities lining Tajikistan's border with Afghanistan.

But after a three hour drive, we are given disappointing news. Our contact in the area, a local journalist, warns us against traveling on the main (read: paved) road to the border area. While guards on the Afghan side pose no big problem, he says the Tajik guards are jumpy and hostile. Our best bet is to figure out a plan with someone he knows who is from a village on the border.

We get back in the car along with the local journalist and drive for a few miles to a small settlement just off the main road to meet up with the man from the border. A group of men loitering next to a drab three-story apartment block stand to stare at our car as we drive up.

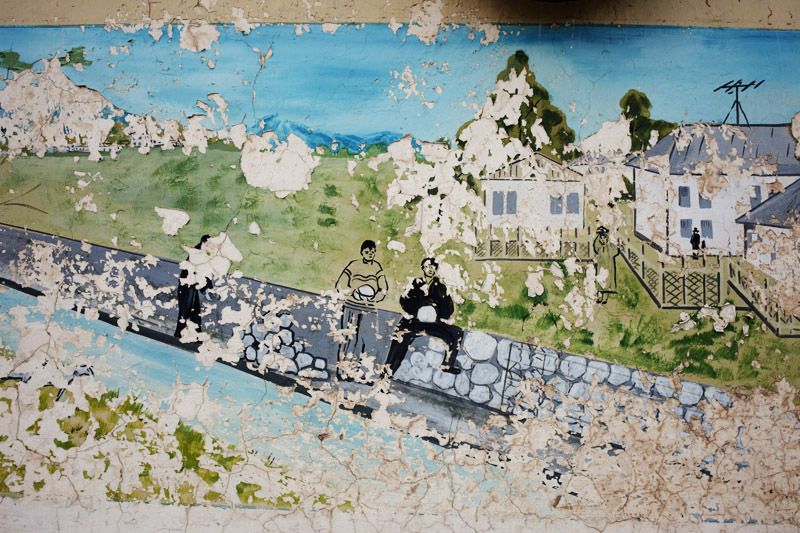

Behind the apartment building are scattered maybe three dozen homes, most with one or two or three cows tied to nearby posts. An outhouse with a shallow pit sits directly in front of the apartment building. Here and there, women are making flat round bread in giant outdoor clay kilns built into the ground. Chickens and children are everywhere. So is poverty. Buildings appear to be falling apart. Livestock look severely undernourished. There is little sign of a cash economy. In a far corner of the village behind a wooden wall, boys play soccer in an abandoned lot. I can't make out whether the ground is concrete with grassy patches or grass with a lot of pieces of concrete strewn about.

The man from the border village gives us one option. We can take a back road over one of the mountains, which should allow us to avoid Tajik officialdom. The journey takes two hours each way, however, and it's already 3pm. We could spend the night in the border village, but that means we will need to somehow drive all the way back to Dushanbe in time to make our 2pm flight to Khojand, a city in Tajikistan's north.

We decide to go for it.

We get back in the car, now with the guy from the border village in the front seat. He looks ancient but he later tells me that he's 54 years old. He wears a square Tajik hat and talks a lot with our translator, Rovshan, a twenty-year old Tajik university student.

The man from the border seemed just fine with the whole thing when we set out. But once on the back road, he started to reel out ominous warnings like an oracle with a migraine. The road, which started paved but quickly turned into a kind of gravel mash, will only get softer and narrower. We really should be in an SUV, he tells us. We will eventually have to cross a shallow river bed and if it rains we will get stuck. There's no cell coverage in the mountains.

As if a gift from the god of clichéd story omens, dark clouds start to gather above us. Then we turn on a particularly scary mountain overhang. It starts to drizzle.

We tell our driver to take us back to Dushanbe.