October 14, 2015 | Pulitzer Center

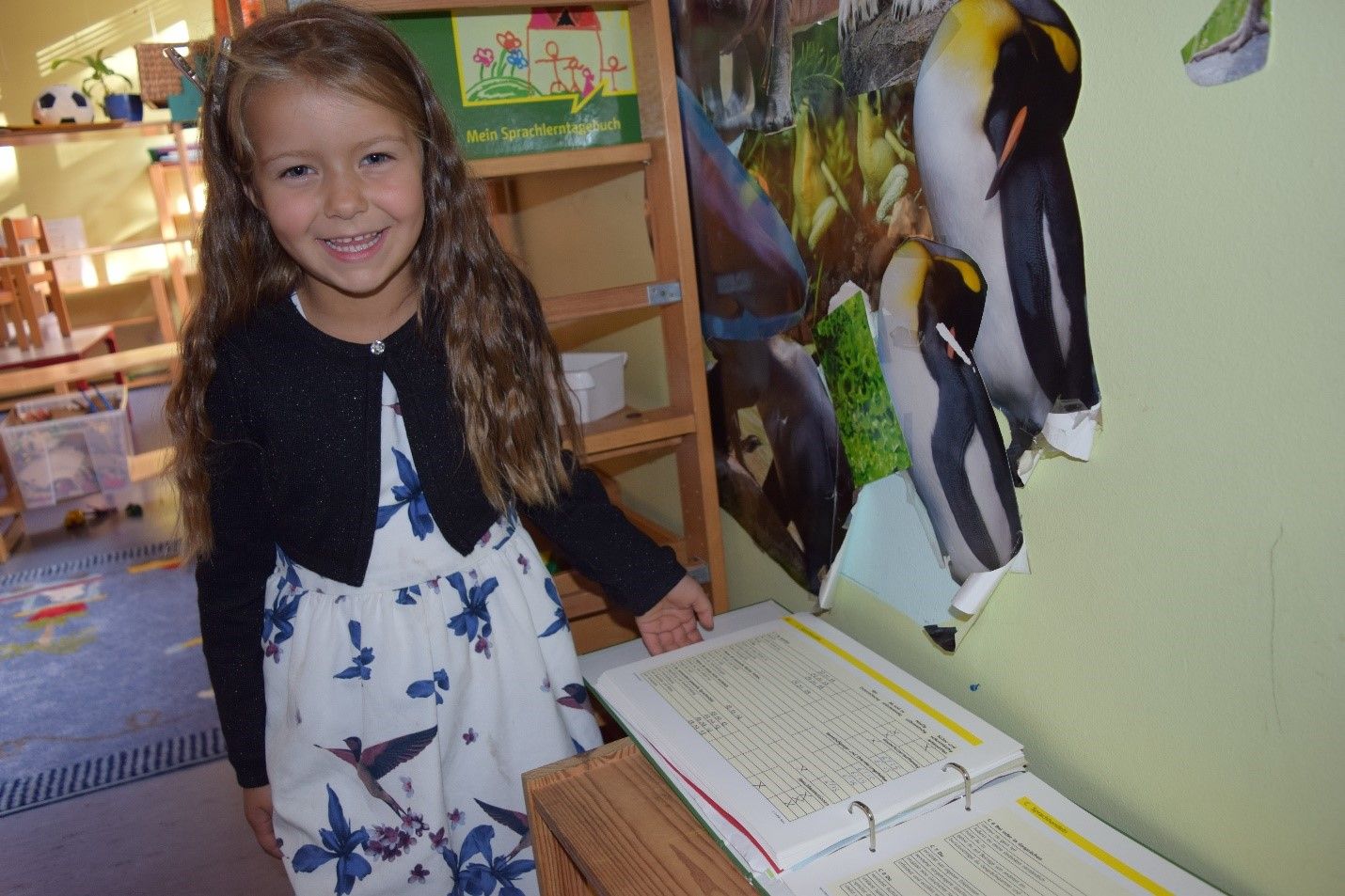

Five-year-old Yade Sönemezo is a student at the Europa Kita in Berlin, a bilingual kindergarten where children learn both Turkish and German simultaneously. Her big sister, 12-year-old Ela, goes to school just across the way at the Carl-von-Ossietzky School, where most subjects are taught primarily in Turkish, with supplementary courses in German. The girls gave me a tour of their schools one afternoon and explained what it’s like to learn in an environment where both of their native languages are of equal importance. Theirs are the faces of intercultural learning in Germany.