I flew to Nigeria in July to report on a low-cost, high-impact health intervention that the government has officially adopted as part of its strategy to lower its extremely high neonatal mortality rate, which is the number of infants per thousand live births who die within their first 28 days of life. (In Nigeria the figure is 34 deaths per 1,000 live births; in the United States, it’s four, in the European Union it’s two, according to the UN Interagency Group for Child Mortality Estimation.)

One of my first conversations was a brief chat with the Nigerian country director of a large United States NGO. He was a physician, and I had brought up the fact that the United States health care system, like Nigeria’s, was also dysfunctional. “Ah,” he said, “but at least in the United States, somehow, people get treatment.” Here, he said, if you can’t pay for the medical treatment you need, “they let you die.”

I noted the remark, and, like a lot of what people tell reporters anywhere in the world, assumed a slight exaggeration. It wasn’t.

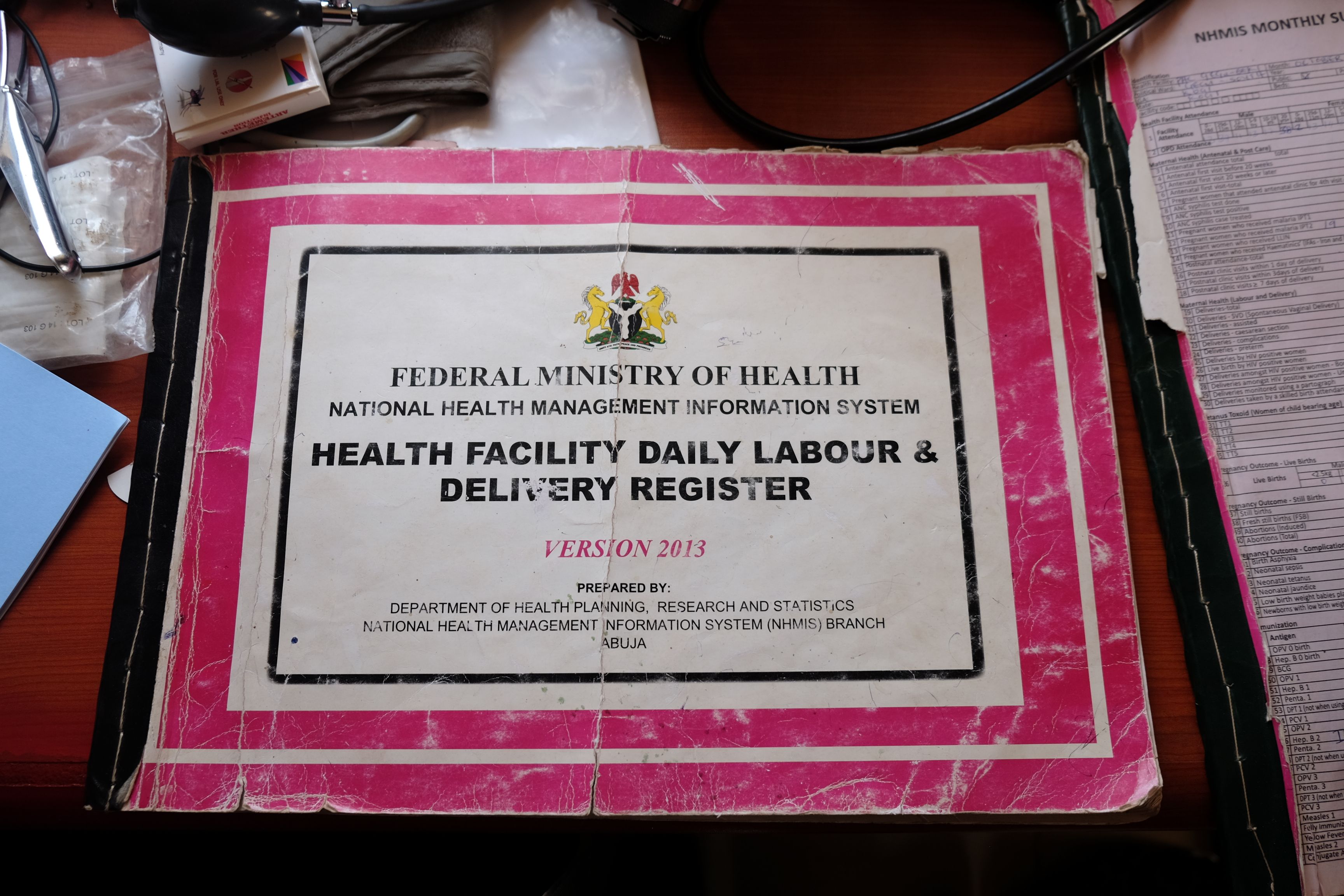

My trip involved a visit to two hospitals in the relatively poor state of Kogi, just south of the capital, Abuja. We had stopped in the maternity ward of a ‘secondary health facility’ in Okene, a hospital run by the Kogi State Ministry of Health. The staff included four doctors, all of whom were general practitioners but who also delivered babies.

The chief maternity nurse, called “the matron,” was born and raised in Okene, and had been at the hospital for more than 25 years. She was frank and funny and spoke English in a Nigerian accent so strong I had to ask the two younger Nigerian doctors accompanying me to translate.

We had hoped to arrive at a hospital during a birth in order to see how the nurse used chlorhexidine, the low-cost, high-impact intervention I am writing about, and that is smeared on a baby’s umbilical cord soon after it is cut. Bacterial infections that enter the body through freshly-cut umbilical cords kill tens of thousands of Nigerian infants every year. Applying a coating of chlorhexidine gel to the newborn’s umbilical cord has the potential to markedly decrease neonatal mortality levels.

“There is a woman who needs a C-Section,” the matron told us. “She is suffering from cord prolapse and her baby is in [fetal] distress. But we are waiting for her to collect the money,” she added, referring to the money needed to pay for the operation.

Cord prolapse, which occurs when the umbilical cord comes out before the baby, is a dangerous condition that almost always calls for an immediate C-section. That’s because the prolapsed cord can inadvertently be squeezed as the fetus moves through the birth canal, reducing the critical blood flow the fetus needs as it’s being born. The C-section would cost ₦15,000 (about $45), with an additional ₦15,000 to pay for the gauze and sutures and other equipment, including quite possibly the anesthesia as well.

“It’s supposed to be an emergency,” she said with a matter-of-fact resignation. “But it is no longer an emergency because of financial constraints.”

“Whose constraints?” I asked. “The mother’s,” she replied.

Suddenly, as we were standing in the recovery room, a baby was whisked into the ward in a metal basket, wrapped in a piece of colorful, Ankara cloth. It was the child the matron had been talking about. The birth had in fact been delayed, and the child had been given oxygen as a result, the matron told us. It was hard to assess how the baby was doing; there was no machine to monitor the infant’s vital signs. The baby simply lay in the metal basket, which had been placed on a bare bed, waiting for his mother to leave the OR.

The matron’s deputy took the baby out of the basket, triple-gloved her hands, and dressed the baby in newborn clothes, including a cap for his head. At the foot of the bed was a blanket and a small packet of diapers, part of the essential care package mothers are expected to bring to the hospital. The nurse rubbed chlorhexidine gel the length of the cord, which was very long, so that it was completely covered.

After a few minutes the baby let out a brief, fragile cry, and one of the doctors with me replied with the ubiquitous phrase Nigerians use as both a greeting and a response. “You are welcome,” she said.