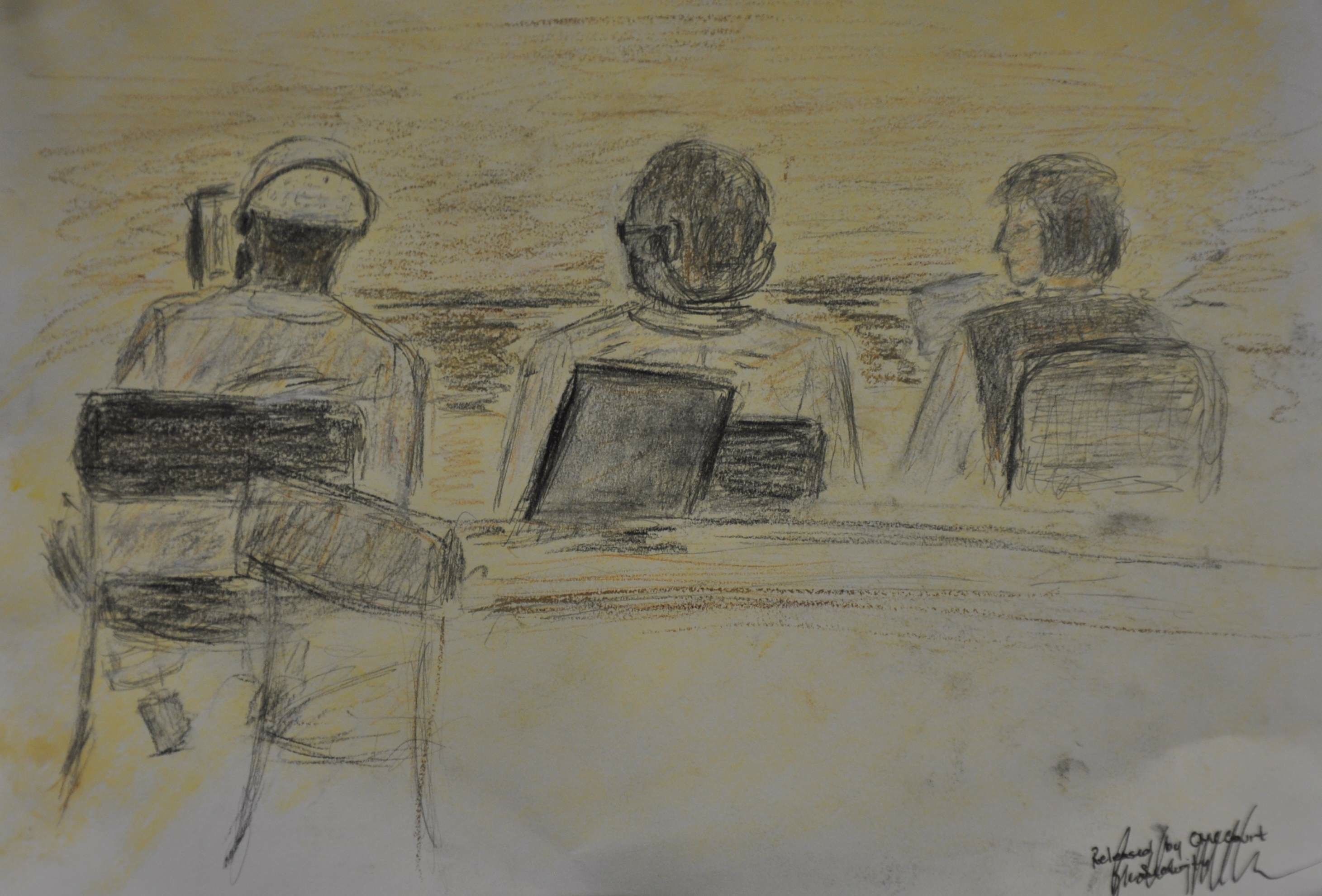

He is a blank canvas, his slight body barely present in a room full of military officers wearing medals and lawyers in gray suits arguing over his fate. Noor Uthman Muhammed, Guantanamo inmate No. 707, plead guilty on Tuesday to two charges, providing material support for terrorism and conspiring to provide material support. For the past three days he's been back in Courtroom Two here at Camp Justice, Guantanamo Bay, sitting at the far end of a wood laminate table — guards in desert camo with ear pieces on one end, his translator and legal team on the other — awaiting his sentence. He is still.

While the others in the courtroom talk among themselves or trade questions with the judge or simply sigh or banter or look worn out, Noor looks away or looks down. He says nothing if not asked, says only Yes when asked. And so during the sentencing phase of this commission — the third to end with a plea deal under President Obama's revamped rules — it is up to the lawyers and military officers to paint whatever picture they can over his pure white robes.

"Terrorists are not born, they are made," Lieutenant Commander Arthur Gaston of the prosecution tells the commission members, nine military officers who make up the jury. As an instructor and leader at the Khalden training camp in Afghanistan between 1996 and 2000, Noor — the government argues —has made hundreds of them.

Zacarias Moussaoui, the so-called "20th hijacker" who was pulled over on an immigration violation before he could ram a plane into the White House? He attended Khalden when Noor worked there.

So did Mohammed al-'Owhali, who took part in the 1998 US embassy bombing in Kenya, which killed more than 200 people.

So did Ahmed Ressam, who was caught trying to bomb LAX over the millennium New Year.

These men, argue the prosecution, all began their terror instruction at Khalden while that slight man in the courtroom, Noor, worked as an instructor. By working at the camp, Noor helped make them terrorists.

And Noor's help didn't stop when the camp closed in 2000, continues the prosecution. Instead, he moved to a safe house in Pakistan run by Abu Zubaydah, a top al Qaeda leader. In the house the men swore a war against America, they planned new terror plots, discussed tactics.

There are monitors in front of each committee member and a large TV at the front of the courtroom. Now they display photos of electrical switches and red wiring caps, Duracell batteries and Casio watches with wires sticking out of them. There's a musical greeting card that's been rigged to detonate a bomb when opened. HAVE A LOVELY EID DAY it reads. These materials are for making improvised explosive devices, the members are told. They were all recovered from the safe house.

More images flash up, excerpts of pages from notebooks and manuals also recovered from the house. An excerpt is highlighted. It's from Abu Zubaydah's diary. "I took them with me away from the flood, one or two individuals from each military science," it reads, "like Noah, peace be upon him, two pairs from each being... they will be the nucleus of my work."

Now more pages, these from a recovered al Qaeda training manual taken from the house: "The psychological impact of beheading is much deeper than by shooting..."

Now a promotional video of Abu Zubaydah. He's bearded, looks strong and healthy. "Enemies of Allah may not rest!" he declares. Somewhere out of view, the committee members are lead to believe, Noor is in the safe house helping to carry forth this mission.

Not today. Today Noor slumps, even as one of his lawyers, Major Amy Fitzgibbons, begins reading Noor's statement to the court. My name is Noor Uthman Muhammed. I am from Sudan. I was born in Kasala, Sudan, which is on the Sudanese border with Eritrea. My family depended on its ability to raise animals and farm to survive.

A very different version of a man appears. This version is a poor boy nomad who ended up doing menial jobs at a low level training camp because he had no other skills, no other prospects.

Fitzgibbons reads and the story unspools with painful detail. An illiterate young orphan passed from home to home, poor but for what money he could make trading at the port market, schooled only in basic letters and numbers. Noor was lost, and he found something more in the Islamic audio and video tapes he was given showing horrible things happening to Muslims in Afghanistan and Bosnia and elsewhere. On them he saw a version of himself that wasn't just poor and jobless and homeless — a version of himself with purpose. He decided he wanted to learn defensive jihad to help these Muslims.

In 1994 he traveled to Khalden, a basic-training camp in Afghanistan, where he stayed to work. At first he was a small-arms instructor, but he hated the job, hated shooting guns all day, asked for something different. He became the supply guy — the person responsible for making sure the camp had enough water and food, fixing things if they needed fixing. It was a good job for him, because it was a job he had been doing his entire life for himself. Besides, he didn't have any other skills. Noor never wanted to be a terrorist. He never helped, planned or assisted in any terrorism attack. He never wanted any of that for himself, the defense argues.

The day before, the civilian defense counsel — Howard Cabot, my father — stood before the commission members during his opening statement, dark tie, white shirt, right hand on the lectern, left in his pant pocket. He was asking questions, throwing them at the committee members:

Can a small arms instructor and food purchaser be connected to 9/11?

Is there evidence of how someone teaching someone how to read the Koran or use small arms could be responsible for 9/11?

Is there evidence of Noor doing anything more than running errands? Evidence of elite training?

Evidence he was in charge of directing camp? Evidence he had any authority or willingness to lead at Khalden?

No.

Noor has pleaded guilty and taken responsibility for the bad choices he's made by working at Khalden, Cabot says. He's owned up for those choices. But he should not be punished for crimes he didn't commit. "The world has seen horrible tragedy from al Qaeda. Those trials are for a different day with different defendants. Noor is not a hijacker or embassy bomber... He is not Osama bin Laden."

The monitors in front of the committee members light up now. This time it's a document, an FBI report on latent-fingerprint examinations. A forensics lab analyzed all the materials taken from the Pakistani safe house. It found fingerprints from 1,050 different people — but not a single one from Noor.

Another document, this one a schematic of the safe house, showing both the ground and top floors. Noor lived and slept on the bottom floor, the members are told, where he cooked and cleaned, as he did at Khalden. The top floor was off limits, some of it's rooms locked. Noor didn't go up there.

Now another, an excerpt from the interrogation of a man captured with Noor. It's highlighted on the screen: The detainee "declared [Noor] did not talk to anyone in the house and would only read his Koran and pray."

More images. A picture of Noor's family in Sudan today. They are sharing a meal with Noor's lawyers, a large platter of food in a modest house. They are smiling and want him home, the members are told.

A letter from the head of Noor's tribe. He wants him home. He promises to help him find a wife and a job.

A letter from an NGO in Sudan that has helped resettle over a half dozen other Sudanese Guantanamo detainees. Each is accounted for and doing well; none has returned to terror activities.

Major Fitzgibbons reads the end of Noor's statement, the fourth and final page:

I was brought to a Pakistani jail.... They held us in big cages and told us that anything could happen to us. There were times that we asked the guards if they could bring us plants that we saw growing in the ground.

In Bagram, I lost all hope that I would ever have a chance to see my family again...

I was never humiliated more than when my clothes were taken away from me in the presence of female guards or interrogators....

We were shackled together and stacked side by side. We were unable to move or use the bathroom. Again when we landed, we were thrown and kicked....

The worst time that I spent in Guantanamo Bay was while I was locked in Camp 5. I was there for two years in a cell by myself. I thought I would lose my mind...

While sitting in the dark, extremely loud music was played or you just hear people screaming. You could spend several hours in this room...

There is complete stillness in the courtroom.

I have never been a member of the Taliban or al Qaeda. I understand that I have plead guilty to Material Support for Terrorism and Conspiracy to Commit Material Support, but I have never planned or participated in any terrorist attacks. I hope to get home in the near future to see my family again before my time on this earth is over.

Everyone stares forward. For a moment every face is like Noor's, blank.

In they come, the nine commission members. They wear military shirts of light blue and beige. They sit. They have been deliberating for six hours.

Throughout the week, the courtroom has risen and fallen with the judge's entry, and later, with the commission's. But Noor stood only once, when he plead guilty. And now he stands, again. Slowly, gently. He puts his jacket down.

Cabot looks over at the jury.

The commission president speaks: "Noor Uthman Muhammed, this commission sentences you to be confined for fourteen years."

Cabot looks down. Noor sits again, puts his hand to a face for a moment. The commission members are excused.

The courtroom remains calm, Noor remains seated, because the proceedings are not done, because the commission members didn't know what's in the pre-trial agreement, which remained sealed until now.

Thirty-four months, the judge says, revealing what the parties have agreed. If Noor fulfills his obligations to cooperate with the government by providing testimony that can be used for future commissions and trials, the remainder of his sentence will be suspended after thirty-four months. If he doesn't cooperate fully and testify about what he knows about Khalden and the safe house and anything else, he will remain in confinement for the full fourteen years. The nine years he has already served in detention will not count in either case.

"Noor," the judge asks, "Do you understand that if you do not cooperate the entire sentence can be imposed?"

Na'am.

The judge leaves. Noor rises, shakes my father's hand, and is lead away by a half dozen large guards in desert camo. The same way he came.