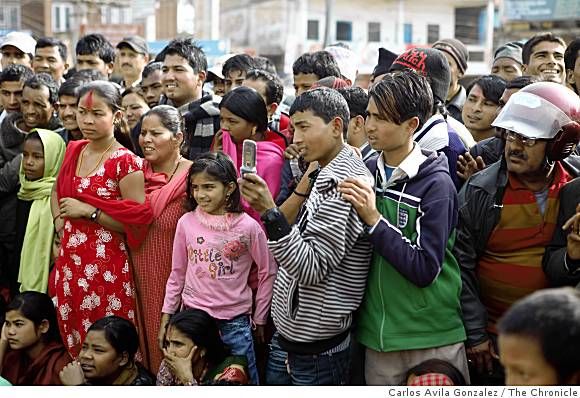

Surrounded by more than 1,000 girls she freed from domestic slavery, 83-year-old Olga Murray of Sausalito marched through this rural town, chanting in Nepali for an end to bonded servitude.

"End the kamlari system!" she shouted, raising her fist in the air.

In a form of trafficking concentrated among ethnic Tharu farmers, destitute families sell their daughters for $75, the equivalent of a third of their annual income, to work as live-in "kamlari" servants in the homes of higher-caste families.

Girls as young as 6 are forced into years of menial labor, cooking, cleaning and babysitting in the homes of strangers. Kamlaris typically work from sunup to sundown, eat leftovers and sleep on the floor and, in the worst cases, are beaten and raped.

Founder of the Nepalese Youth Opportunity Foundation, Murray's passion for the last two decades has been to educate, house and clothe Nepal's neediest children. That includes the kamlaris she finds every January during the Maghe Sankranti winter festival, a major Hindu holiday.

During the weeklong revelry of Maghe Sankranti, kamlari selling hits a fever pitch. The holiday also marks the end of the Nepalese fiscal year and is the one time masters traditionally let their kamlaris return home for a few days.

It's a busy time, when many people are traveling. Brokers from cities throughout Nepal come to the Tharu villages to negotiate or renew one-year kamlari contracts, fathers are making deals and advocates like Murray are trying to stop them.

Murray has a unique way of doing it. She offers a pig or goat to parents who promise not to sell their daughters. Families can make more than they get for their daughter by breeding or butchering the animal. If they accept, Murray will also pay the girls' $100 annual school expenses.

In the last eight years, 3,300 families have taken the deal. Nepalese charities replicating Murray's model have bartered another 1,700 girls out of slavery.

After months of negotiations, 500 more families accepted Murray's goats-for-girls offer during this year's Maghe Sankranti festival.

It's an approach that has earned international acclaim. The former king of Nepal, Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, Oprah Winfrey and the Dalai Lama all have honored Murray.

Although lawyers working for Murray's nonprofit convinced the Nepalese Supreme Court to outlaw the kamlari practice in 2006, cultural resistance has been strong and the government has yet to prosecute anyone for keeping a kamlari.

An estimated 5,900 daughters are sold into debt bondage each year in Nepal, according to aid organizations that have conducted door-to-door surveys.

Murray knows of 40 kamlaris who simply disappeared.

Generations of debt

The Tharu are sharecroppers who live in mud huts without electricity or running water in five of Nepal's 75 districts. The Dang, Banke, Bardiya, Kailali and Kanchanpur districts are agricultural lowlands of the Himalaya, on Nepal's southwestern border.

Sixty years ago, the Tharu owned their farms and lived in relative isolation, immune to malaria common to the Terai plains. But with the advent of anti-malarial drugs, new settlers moved in. The illiterate Tharu lost much of their land, swindled by fake loan documents, or enticed by bottles of alcohol. They became "kamaiya," or tenant farmers, passing increasing debt from generation to generation.

Some landless Tharu offer their daughters to farm landlords to keep from losing their plots, said Som Paneru, executive director of Murray's charity. When daughters of the new landlords got married, they took the kamlaris as dowry when they moved in with their husbands, and the kamlari custom spread to the rest of the country.Now, people from throughout Nepal come to the rural districts to buy girl servants.

Families often think their daughters will be better off - many employers promise to send kamlaris to school, but that rarely happens, Murray said.

"These families love their daughters, but they figure it's better to send her away than let her starve," Murray said. "But these girls are so easily abused."

Motorcycle men

In the waning days of Maghe Sankranti, several men on motorcycles, conspicuous with their leather jackets, sunglasses and cell phones, cruised the mud huts of a Tharu village in the Kailali district.

They are labor contractors looking to buy kamlaris.

One motorcyclist, Karna Kunwar, a journalist from the nearby town of Tikapur, said he was in the village to renew his 16-year-old kamlari's contract. He noted that kamlaris are becoming controversial, but explained that the rural girls get a chance at a better life.

"Girls from here, when they go to the city, they get luxuries like TV and better dresses and good food," he said. "When they come home for Maghe, they say they like their freedom, but after 10 days or so, they start missing that city life."

Naresh Bahadur Shasi, a clothing store owner, walked through the village talking into a cell phone as he searched for his 10-year-old kamlari's home. He planned to buy her for a second year for $80, and find another servant for his second home.

"Some organizations are saying no to the kamlari system, but clearly this is a private business," Shasi said.

Shasi found the hut, but the deal did not go as planned. The father, complaining he never could reach his daughter when he called Shasi's house over the past year, refused.

His wife was furious he wouldn't sell.

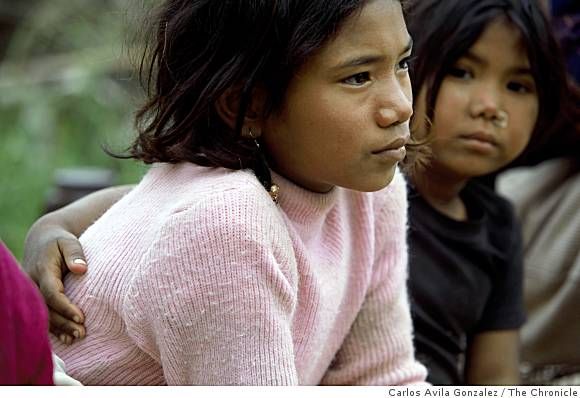

"Maybe our daughter will see how poor we are and want to earn some rupees for us," she said, looking down at Kausi Chaudhary, (all Tharu share the same last name), who sat silently between the adults on a handmade leather-strap bench, listening to her fate.

After Shasi left to look elsewhere, Kausi's father gave the real reason he wouldn't sell.

Earlier that morning, he said, another man came by with a better deal - $95 with half the money up front.

Finding her voice

Urmila Chaudhary, 19, is the new face of the kamlari.

Less than two years out of debt bondage, she has become the leader of the largest kamlari resistance movement, the Common Forum for Kamlari Freedom, representing 1,600 former girl slaves.

She unveils the horrors of her captivity on weekly radio programs, in street plays and marches. She knocks on doors in Tharu villages to dissuade parents from selling their daughters.

Sold by her father when she was 6, she wound up serving a Kathmandu family of 15.

"I'd clean one dish and another would appear - it was never ending," said Urmila.

They often beat her for what they said was shoddy housework, and once threw boiling water on her as punishment, she said.

A year ago, her brother helped her escape. With Murray's help, Urmila and hundreds like her have returned to school in Dang. Urmila is in the fifth grade and hopes to become a journalist.

"Olga is like our mother - bigger than mother," said Urmila.

So many former kamlaris have come home that Murray funded the construction of 36 classrooms to accommodate them. Collaborating with her Nepal-based sister charity, Friends of Needy Children, Murray has started a henna co-op farm, sewing programs and a driving school to teach girls how to operate electric three-wheel "tempo" taxis.

Childhood lost

In Kohalpur, the largest town in the Banke district, Murray paid a visit to kamlari Jamuna Chaudhary, 18, while her owners were out. For the last decade, she has cooked, swept, and washed clothes at an outdoor water pump for the family of four she serves.

"They tricked me; my employer said he'd send me to school, but he never did," she said, in tears.

She wakes at 5 a.m. to begin her chores. By 10 p.m., she curls up to sleep on a dirty mattress under the staircase. She never leaves the propery.

She ended her story when a relative of her master returned."She's too old to go to school, but she expressed interest when we told her we could get her into one of our literacy classes and then a vocational program," Murray said later.

Murray and Paneru make a plan to come back. First they will try to convince her employers to release her. If that doesn't work, they'll send a cease letter citing the Supreme Court ruling.

Ultimately, Murray, who worked for 37 years as a research attorney for the California Supreme Court in San Francisco, will file a lawsuit. Of the 70 cases Murray and her collaborators have filed, half were quickly settled because owners released their kamlaris.

Kamlari-free zone

Following the protest march in Ghorahi, the town center of the Dang district, Murray joined the thousands of former kamlaris in a field, surrounded by trees covered with fruit bats. From a brick gazebo, the local district leader declared Dang a "kamlari-free zone."

Murray clapped from the stage, but later said she worried the declaration would be largely symbolic, like the 2006 Supreme Court ruling.

"The nature of our government has always been to make promises to the community and never follow up," said Parliament member Shanta Chaudhary, 28, who spent 18 years as a kamlari.

When she was elected three years ago and began speaking in government meetings about the kamlari system, few of her 600 colleagues knew what she was talking about.

"The kamlari practice might not go away soon, but it will go away. It will," she said.

It's difficult to change an entrenched cultural tradition, said Murray, whose Nepalese Youth Opportunity Foundation employees have received telephone threats in their Kathmandu office.

During this year's Maghe Sankranti festival, she and Paneru discovered kamlaris working for high-ranking Communist Party leaders, lawyers, journalists and police - and even for a woman who raises funds for children's rights in the Kathmandu office of the United Nations Children's Fund.

"You can see why it's so hard to work on this issue," said Paneru. "They all have kamlaris, and nobody wants to talk about it."

However, Dang's kamlari-free designation is a first for Nepal, and is a sign of hope, Murray told the former kamlaris from the rally stage.

"Now begins a new day for the daughters of Dang," Murray said over the rally microphone, sporting a fuchsia tikka mark on her forehead, a common Hindu blessing. "No longer will your little sisters have to go work in the homes of strangers. You can be anything you want now because education makes everything possible."

Days later, more than two dozen kamlari traffickers were arrested in Dang, according to a report in the Kathmandu Post. It's the first time the police have arrested a kamlari trafficker, Paneru said.

Searching for Gita

Murray scanned a chaotic roundabout in Kohalpur in the Banke district, undaunted by the diesel-chugging microbuses, ox carts and orphans begging for food.

Her team of Nepalese-speaking volunteers were boarding buses, looking for kamlaris traveling for the Maghe Sankranti festival. By asking a few questions, they try to find out where the girls live so Murray can offer their parents an animal in exchange for a promise not to sell them.

There's a commotion near one of the packed microbuses. A Tharu girl, no older than 10, is clinging to the arm of a well-dressed woman with painted nails and jewelry.

A crowd forms and there's a lot of shouting as the woman tells the little girl how to answer Paneru's questions.

The girl is a kamlari, her name is Gita Chaudhary and the woman is her employer. The woman says she is returning the girl to her village in the Dang district for a few days to celebrate Maghe Sankranti with her family.

Murray and Paneru do their best to persuade her to give up her kamlari, but fail. The woman boards the bus, pulling Gita behind her.

The next morning, Murray and Paneru navigate through the fog in a four-wheel drive Jeep to Gita's village.

But the residents didn't know Gita.

The information Paneru had written down after questioning the woman at the Kohalpur bus stop was bogus. The woman had lied.

"Gita Chaudhary is a name like Jane Smith," Murray said. "She probably lied about that, too."

There was nothing to do but get back in the Jeep.

"That's the hardest part," Murray said. "When these girls just disappear."

Goats for girls

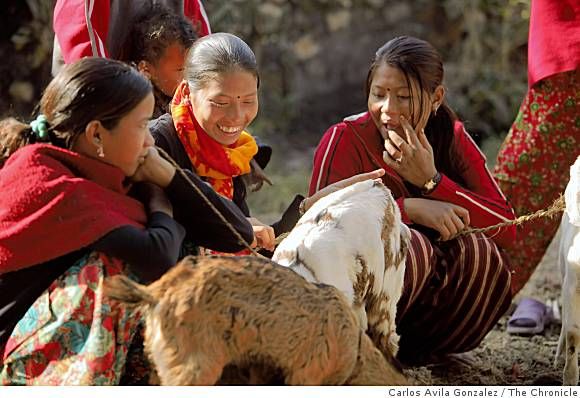

Early one morning, not far from where Murray marched with the kamlari protesters, five kamlaris gathered in a dirt yard off a steep alley of tenement homes.

They were smiling. Maghe Sankranti was over, but this time they would not be returning to someone else's house to cook and clean. After several months of negotiations, their parents had agreed to let Murray educate their daughters in exchange for a baby goat.

The girls looked over the animals trying to decide which one to bring back to their families.

As Murray and a social worker from Friends of Needy Children put ropes around the wriggling animals, Yamkumari Chaudhary was elected to make the first pick because she had been a kamlari the longest - five of her 17 years.

She cooked, did the laundry, washed dishes and collected animal dung for fertilizer as a servant in Kathmandu and Nepalgunj.

She pointed at the white one.

Murray handed the goat's rope to Yamkumari. She brought her hands together in prayer, touched her fingertips to her forehead and bent forward.

"Namaste," Murray said, using the Nepalese greeting of goodwill.

Yamkumari did the same.

"This goat is my freedom," she said. "When I was a kamlari, I wanted to escape but I didn't have any money. I'm going to take good care of this goat so it has many babies."