Sex workers gathered at a meeting in Cape Town say it isn’t the clients they service they are most scared of – it’s the police.

Angie de Bruin, a former sex worker turned paralegal and sex worker rights activist, says South African police took her condoms while she was working just because they felt they had the power to do so. She says police and hospital workers taunted and publicly humiliated her in an attempt to remind her that to them she is nothing but a prostitute.

“Police are taking advantage of the sex workers. They do everything in their power to get rid of sex work. They rape sex workers,” de Bruin said. “It’s horrible. Not terrible, it’s horrible.”

The Sex Worker Education & Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT), Sisonke (a self-described "movement of sex workers, by sex workers"), and the Women’s Legal Centre recently released a study based on interviews with 308 sex workers. “Stop Harassing Us: Tackle Real Crime” finds that approximately 70 percent of sex workers have been abused by police. The main types of abuse include assault, harassment, arbitrary arrest, violation of procedures and standing orders, inhumane conditions of detention, unlawful profiling, exploitation, bribery and denial of access to justice.

De Bruin explains that when police arrest a sex worker they will sometimes ask for sexual favors in exchange for the sex worker’s release. Sex workers who bring a legal case against police who have abused them have also been targeted and beaten up in retaliation.

“I knew one case where the police even kicked the girl in the stomach and she was supposed to get married. She had to postpone the marriage and they came afterwards and made fun of her,” de Bruin said.

A female sex worker interviewed for the study says, “A police officer unzipped his pants and put a condom on...He put me on the floor. The police officer raped me, then the second one, after that the third one did it again. I was crying after the three left without saying anything. Then the first one appeared again...He let me out by the back gate without my property. I was so scared my family would find out.”

Another female sex worker adds that after being held all night by police, driven around and pepper-sprayed, she went to the police station to report the abuse.

“I told them I want to lay a charge against a police officer who keeps harassing me. And they laughed at me and said that is his job.”

De Bruin says the high rate of unemployment in South Africa often leads people to sex work as a means to survive – a way to support themselves and their children. Sex work is illegal in South Africa but organizations like SWEAT are working to decriminalize it.

“We try and bring a general awareness to people that sex workers are still human regardless of their profession and still deserve to enjoy the same human rights that we all enjoy,” Ntokozo Sibahle Yingwana, an advocacy officer at SWEAT said.

Yingwana explains that decriminalizing sex work would allow sex workers to realize their human rights given to them under the constitution, but adds that while working on law reform, they must simultaneously fight to reform the ingrained and negative opinions many South Africans have of sex workers.

“Our greatest challenge really is changing people’s mindsets at the lowest level possible because we realize that it’s only from the community and the society that our lawmakers will take [our] word on what laws to change,” Yingwana said.

The “Stop Harassing Us: Tackle Real Crime” study also finds that sex workers are often abused by police as a direct result of their criminal status which increases their vulnerability to violence and inability to seek justice.

“The current legal framework forces sex workers to the margins of South African society, where they are easy targets for abuse at the hands of police and clients. The only remedy is to change the way in which the sex work industry in South Africa is viewed under the law and by the institutions responsible for its administration,” the study states.

The idea of decriminalization is not new. During the World Cup of 2010, it was seriously considered in an effort to accommodate the influx of soccer tourists, but was never passed.

In August 2012, while speaking at the National Sex Work Symposium in Johannesburg, Deputy Minister of Police Maggie Sotyu called for sex work to be decriminalized “so it can be professionalized and police brutality against sex workers can be eradicated.” This vocal support is a big step forward as current decriminalization legislation is stagnant.

The laws regarding sex work that are now in place in South Africa are the same as when they were first passed in 1957, a remnant of an apartheid past from a time when it was an accepted practice for the police to exert their authority and at times brutal power to enforce the law.

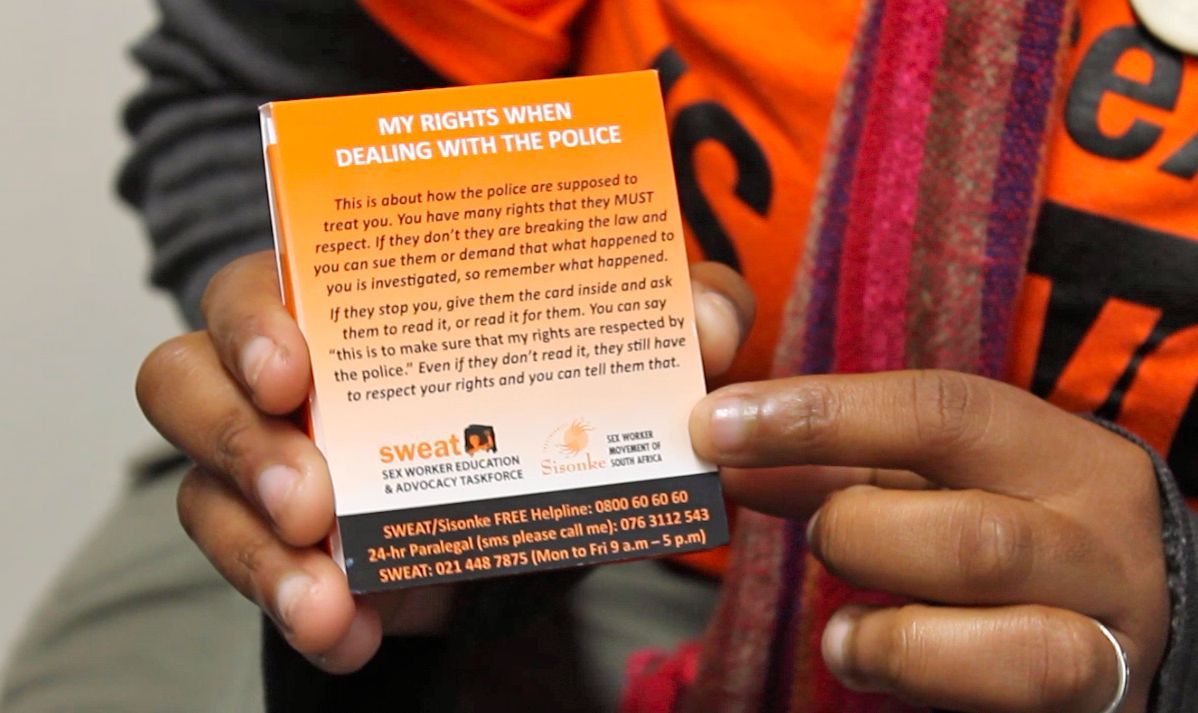

SWEAT also tries to educate sex workers on safer health practices and solutions for problems ranging from violence to dealing with those clients who refuse to wear a condom. They also distribute packs of cards for sex workers to give to police who confront or harass them.

The message on the card? “Dear Police Officer, Please tell me if I am under arrest. If I am NOT under arrest, then you must let me go.” It goes on to explain a sex worker’s right to silence, right to see the officer’s badge and right to a legal adviser. It also reminds the officer of the sex worker’s right to be treated with respect.

It’s this common lack of respect and perpetuating stigma surrounding sex work that both De Bruin and Yingwana say has stalled legislation decriminalizing sex work.

“Our moral compass in South Africa should be our constitution that has been fought so hard for and what that means is that everyone has the right to their dignity and everyone has the right to a profession that they choose and everyone has the right to operate in that profession without any harassment or abuse or torture,” Yingwana said.