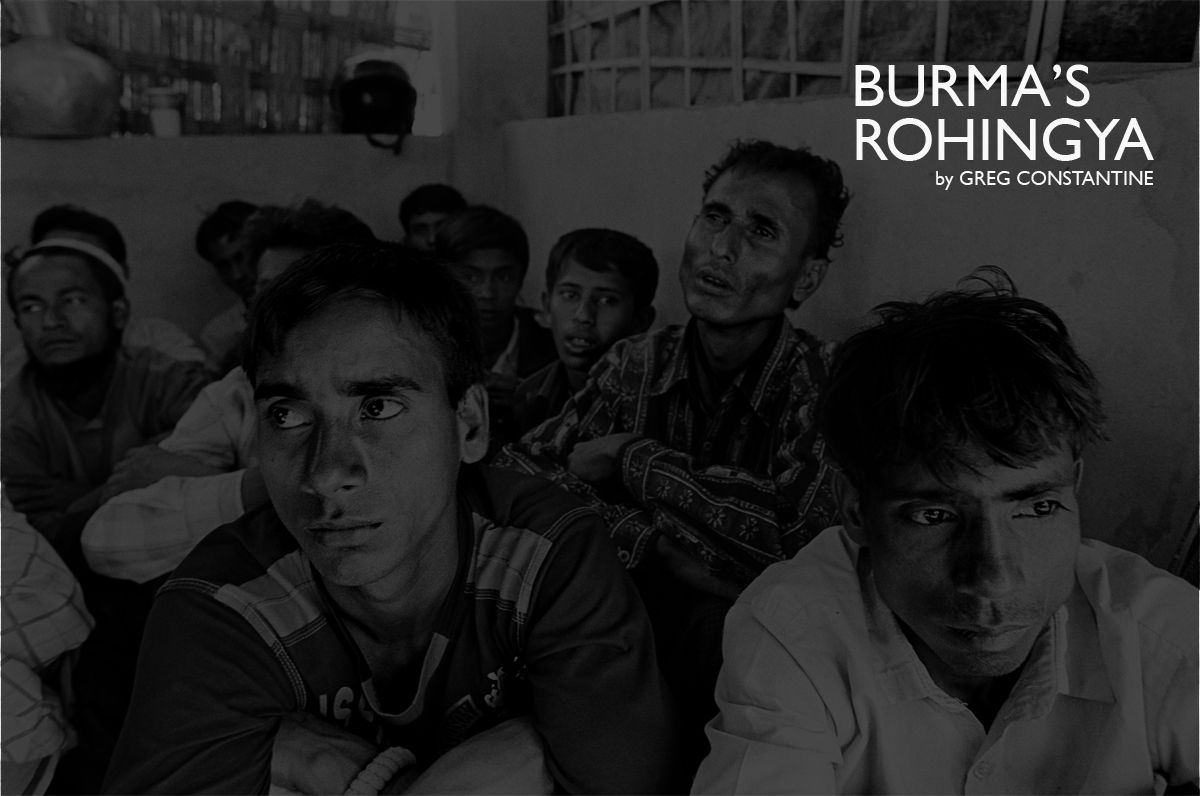

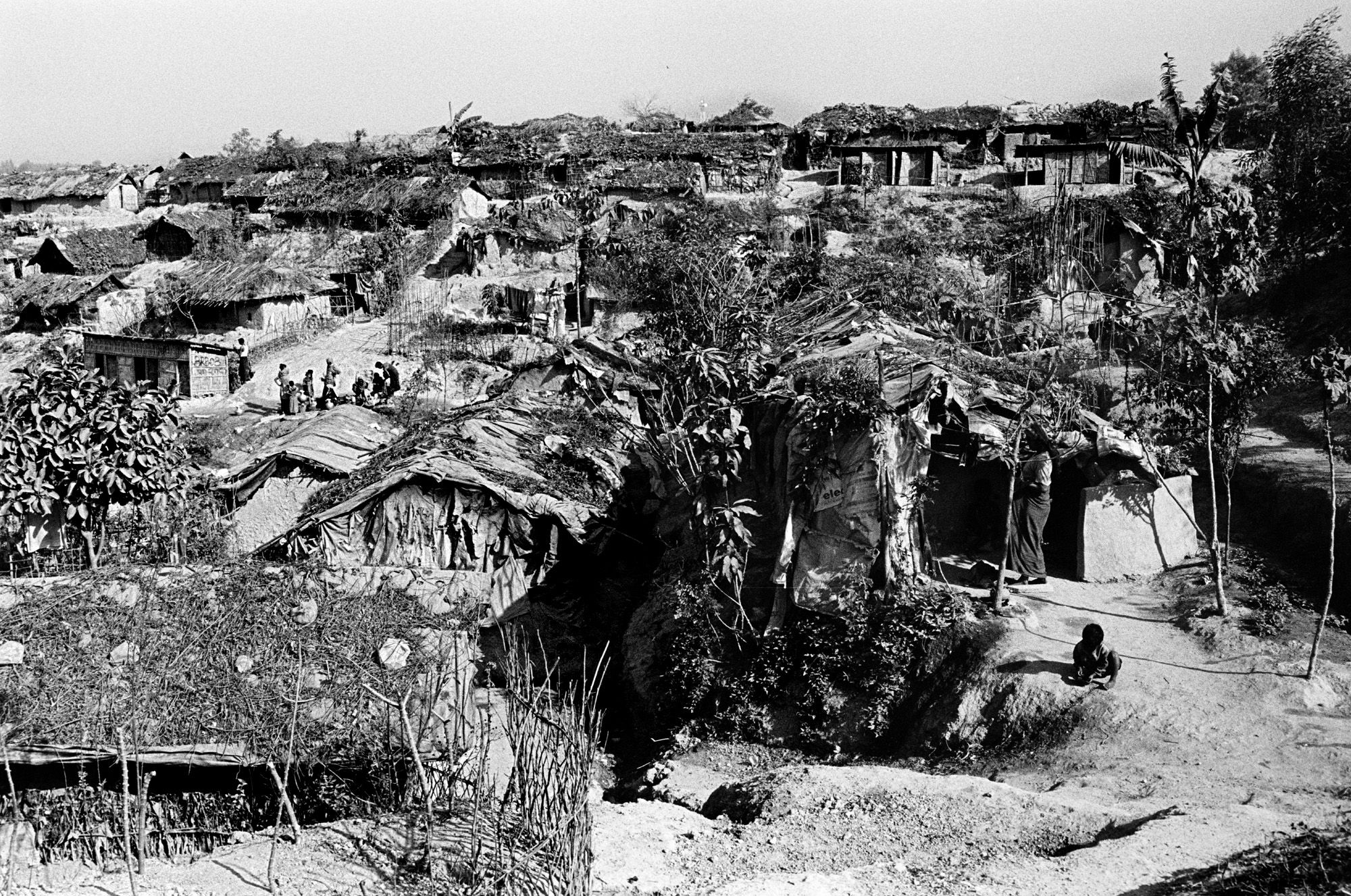

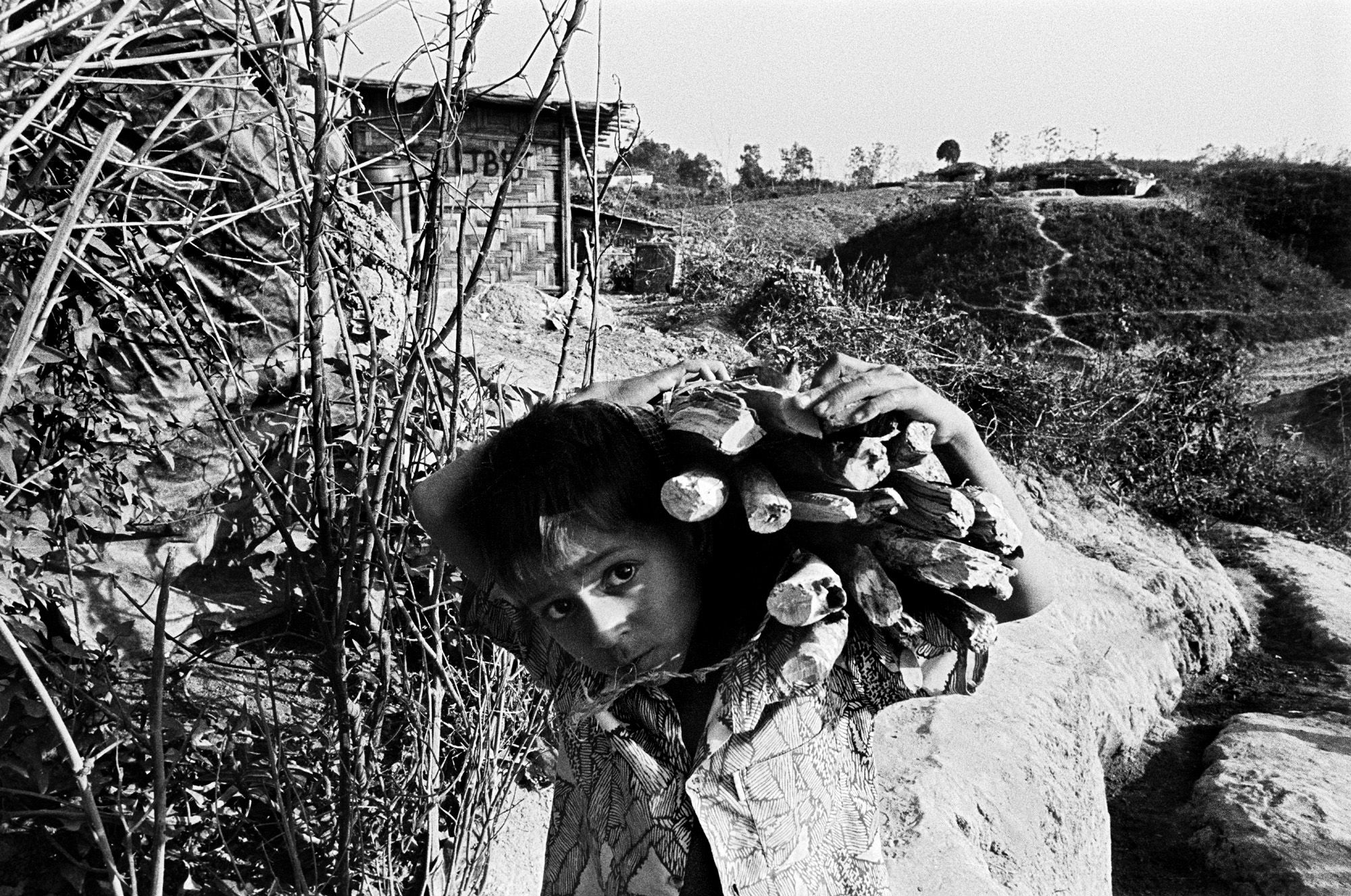

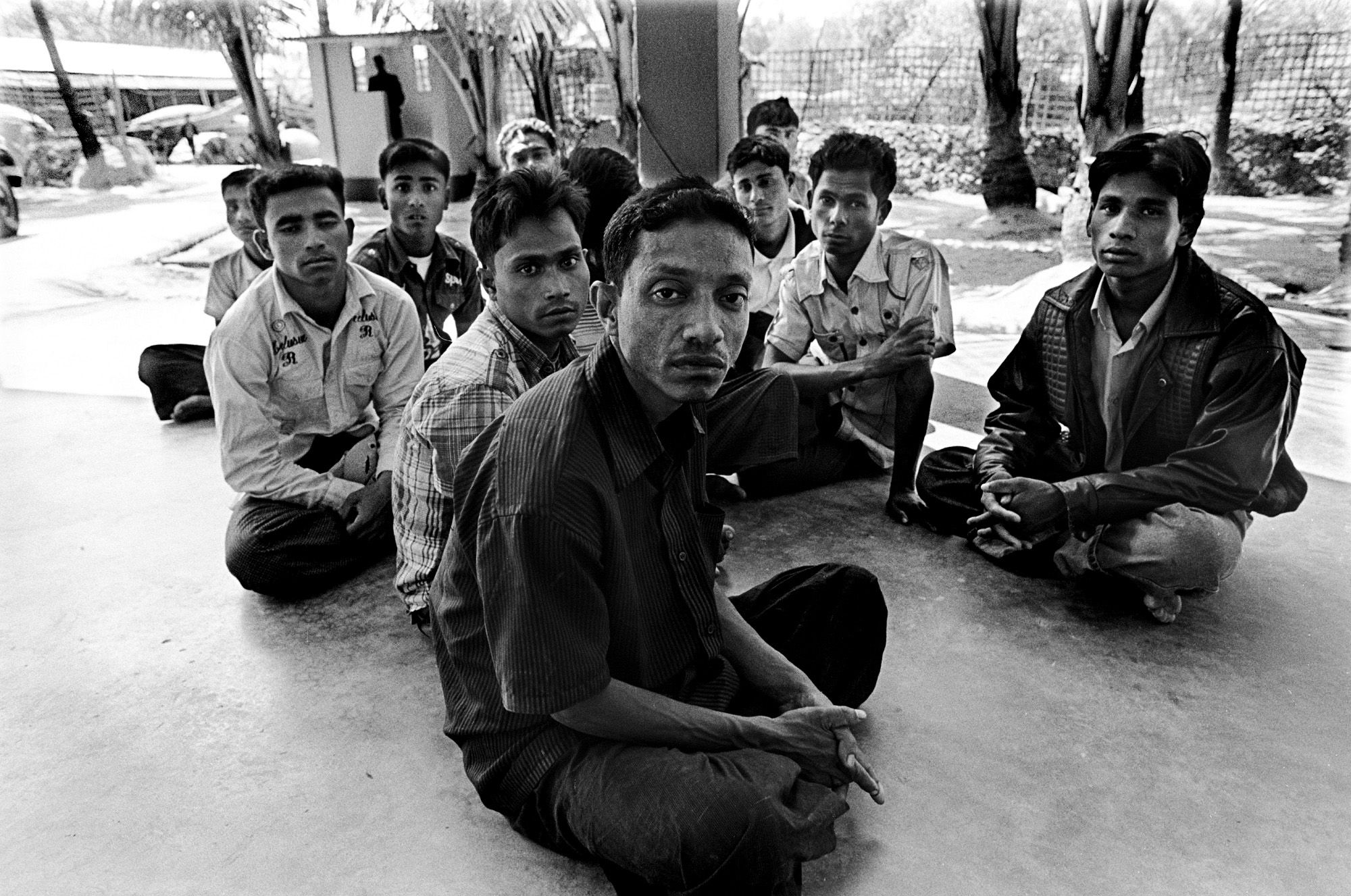

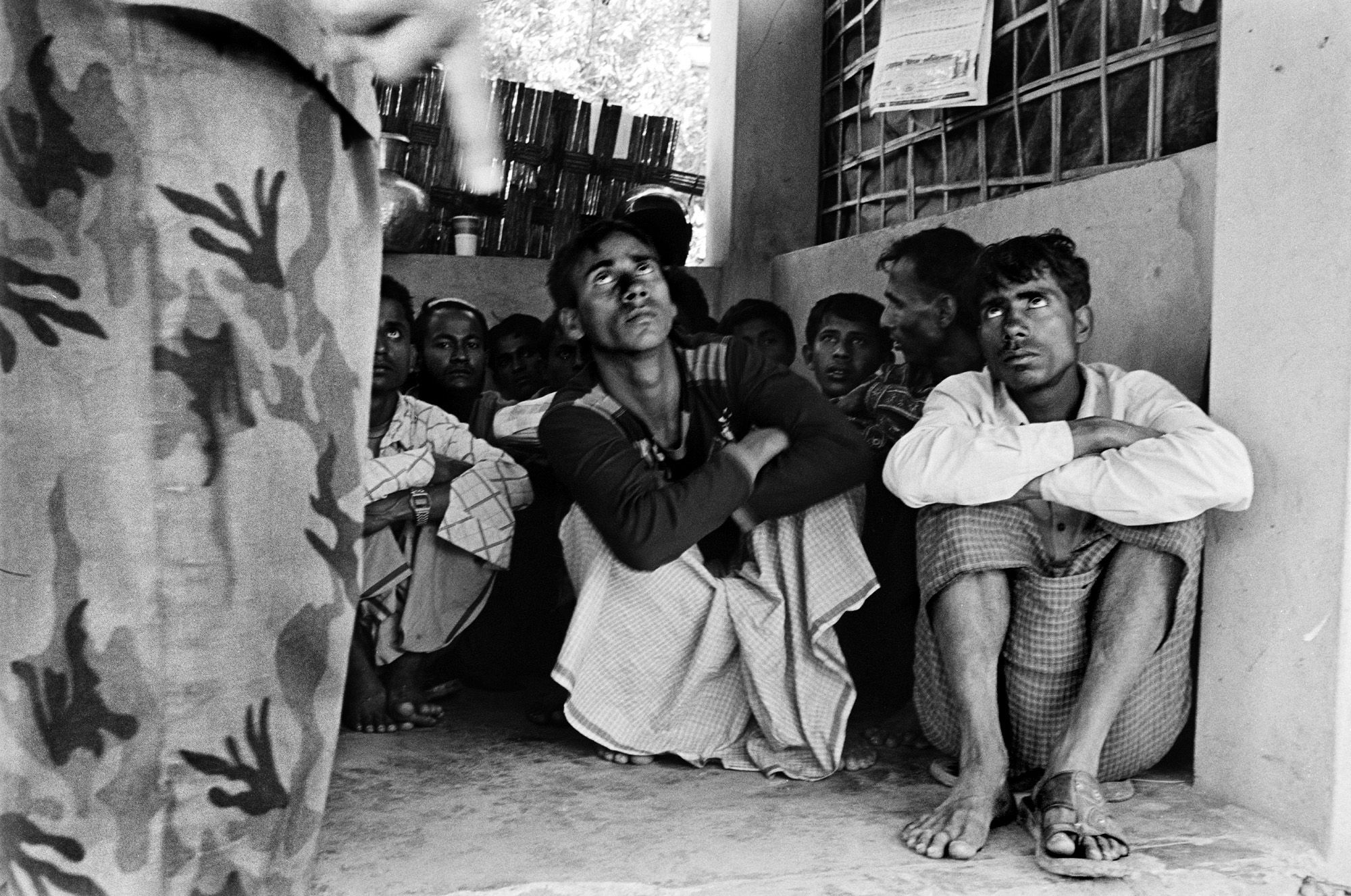

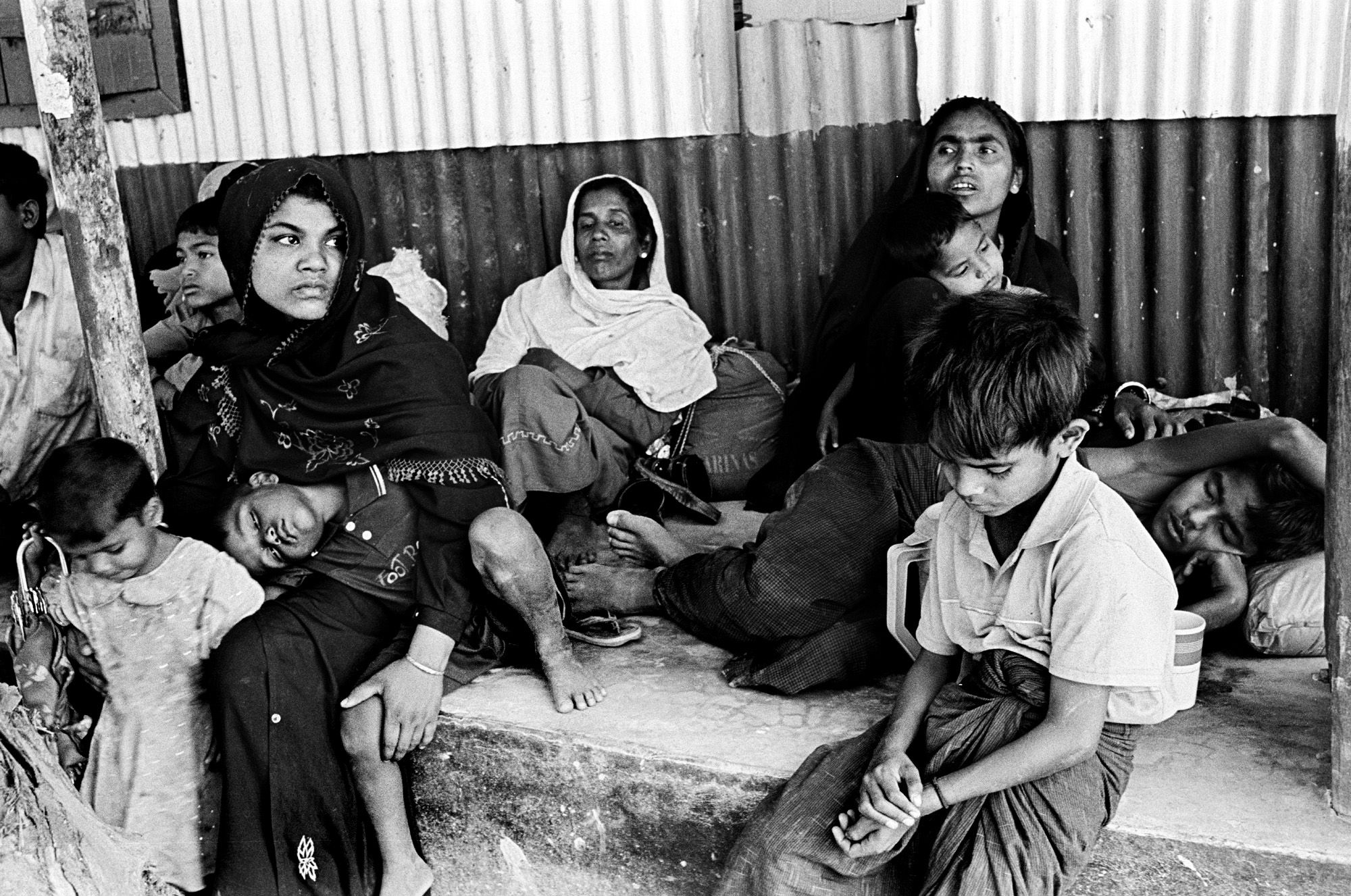

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority from the North Rakhine State in western Burma. Over the past forty years, the Burmese government has systematically stripped over 1 million Rohingya of their citizenship. Recognized as one of the most oppressed ethnic groups in the world, the Rohingya are granted few social, economic and civil rights. They are subjected to forced labor, arbitrary land seizure, religious persecution, extortion, the freedom to travel, and the right to marry. Because of the abuse they endure in Burma, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled Burma to seek sanctuary in neighboring Bangladesh.

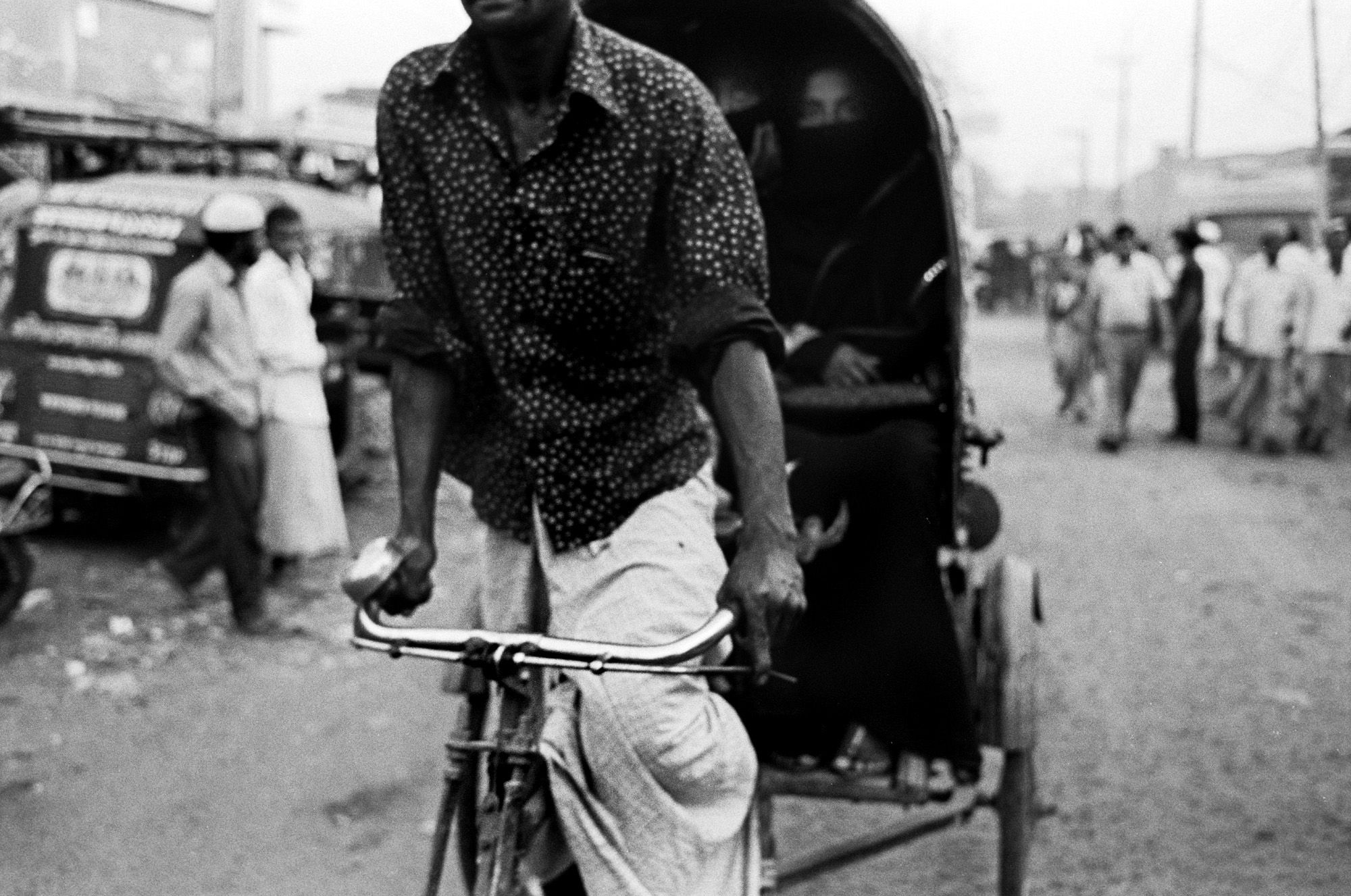

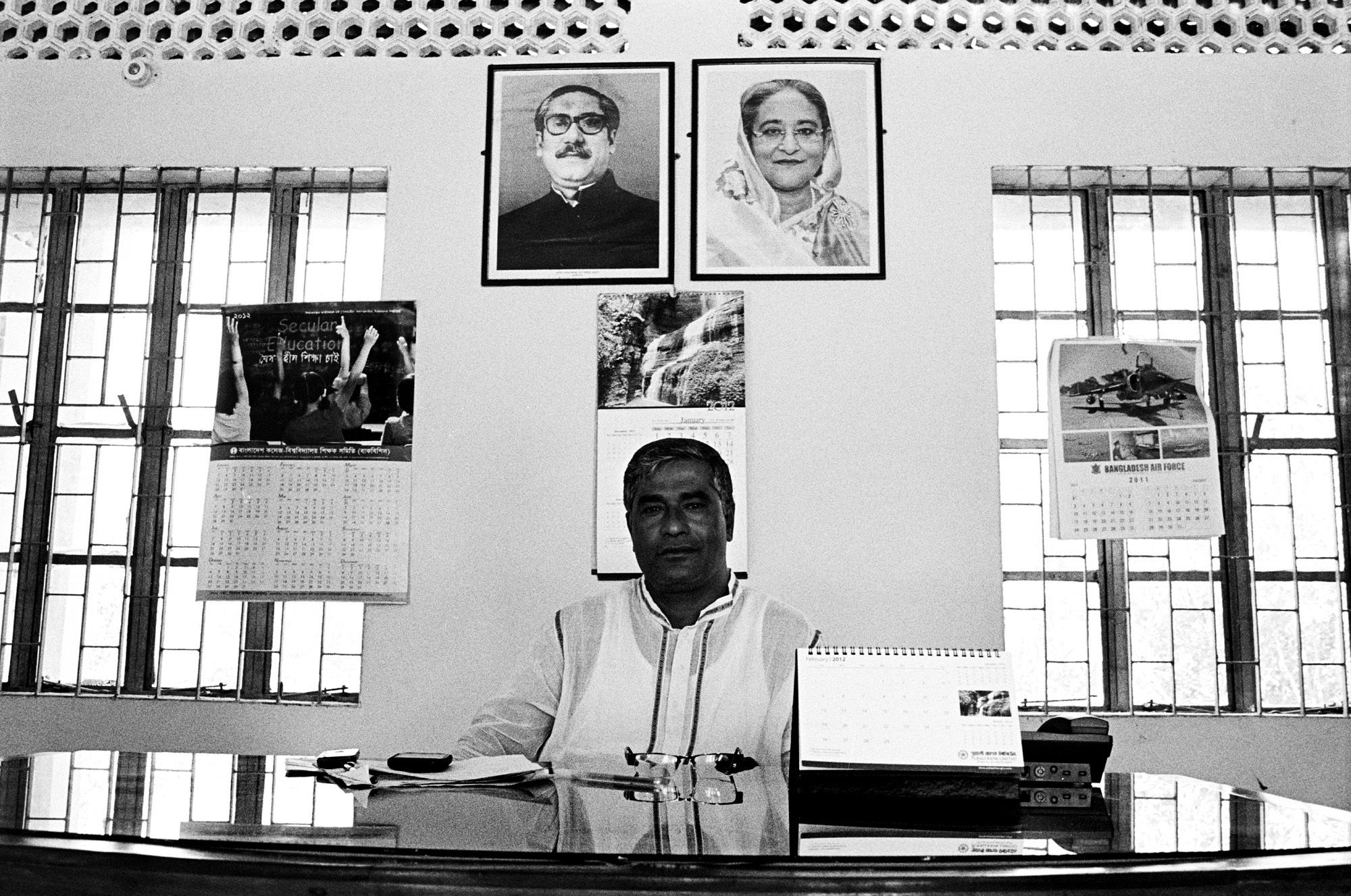

In Bangladesh, most are not recognized as refugees and are considered illegal economic migrants. Unwanted and unwelcome, they receive little or no humanitarian assistance and are vulnerable to exploitation and harassment. In recent years, the Rohingya have paid brokers to smuggle them by boat from Bangladesh to Malaysia and beyond, sparking the attention of governments throughout the region. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has confirmed that the statelessness of the Rohingya is not just a Burma-related problem, but a problem with larger regional implications.