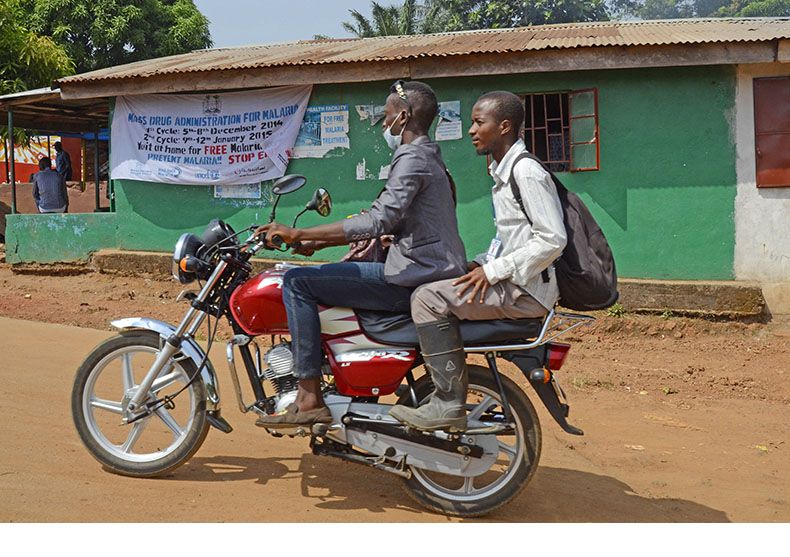

FREETOWN, Sierra Leone—If you’ve even glanced at the news in the past several months, the grainy image of the microscopic, wormy Ebola virus as well as photographs of otherworldly workers dressed in hazmat suits have passed before your eyes. From afar, the contagion devastating West Africa can seem foreign or even reminiscent of bad science fiction—and perhaps that’s one reason why the world responds relatively slowly as the outbreak persists into its second year.

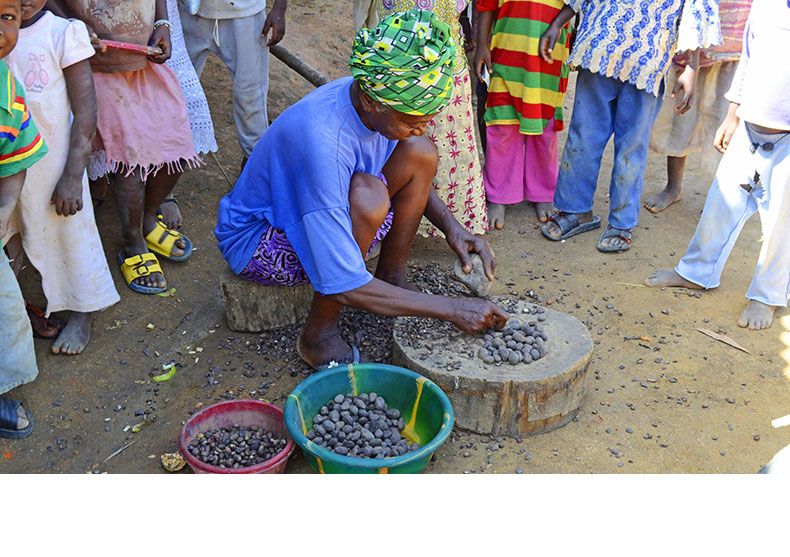

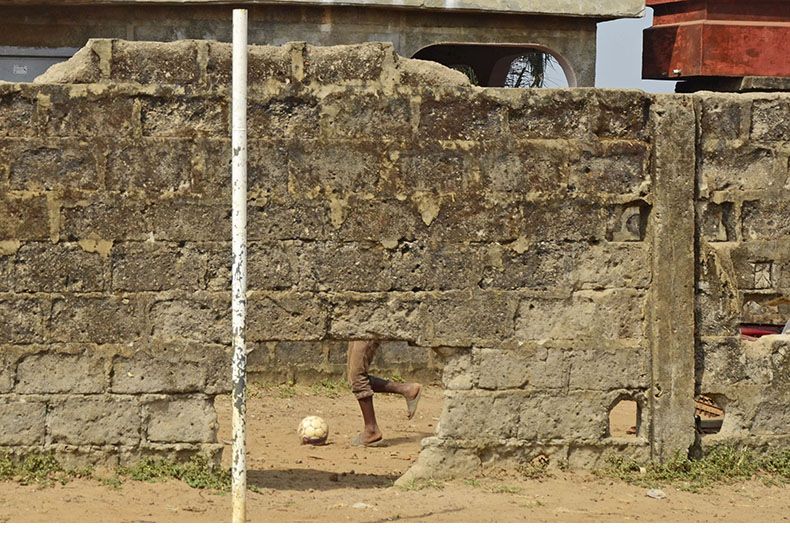

Hazmat suits represent only a slight fraction of what I see on the ground in Sierra Leone while on a reporting fellowship here this month. Although the virus permeates all aspects of life, it’s really in the background. Up front are humans who love, eat, work, pray and play. And none of that feels the least bit foreign to me. In this slide show, I’ve intentionally left out photos of Ebola treatment tents and hazmat suits. You’ve probably already seen that. I want to give you a glimpse of the 99 percent.