BILOXI – The value of oyster reefs, a habitat that has decreased by 85 percent worldwide in the last two centuries, is not lost on Mississippi’s leadership.

“It is becoming one of the favorite food sources around the United States, and they need to buy it here,” said then-Gov. Phil Bryant in 2015. “This is the soybean of the sea.”

While this time of year usually marks the end of the oyster season, this spring will instead mark over a year since a single wild oyster was harvested in Mississippi.

In the summer of 2015, after years of depleted oyster production in the Gulf of Mexico, Bryant created a task force to reclaim the Coast as the “Seafood Capital of the World.” He even set an exact benchmark: harvesting 1 million sacks of oysters from the state every year by 2025, which would mean doubling Mississippi’s most productive season this century.

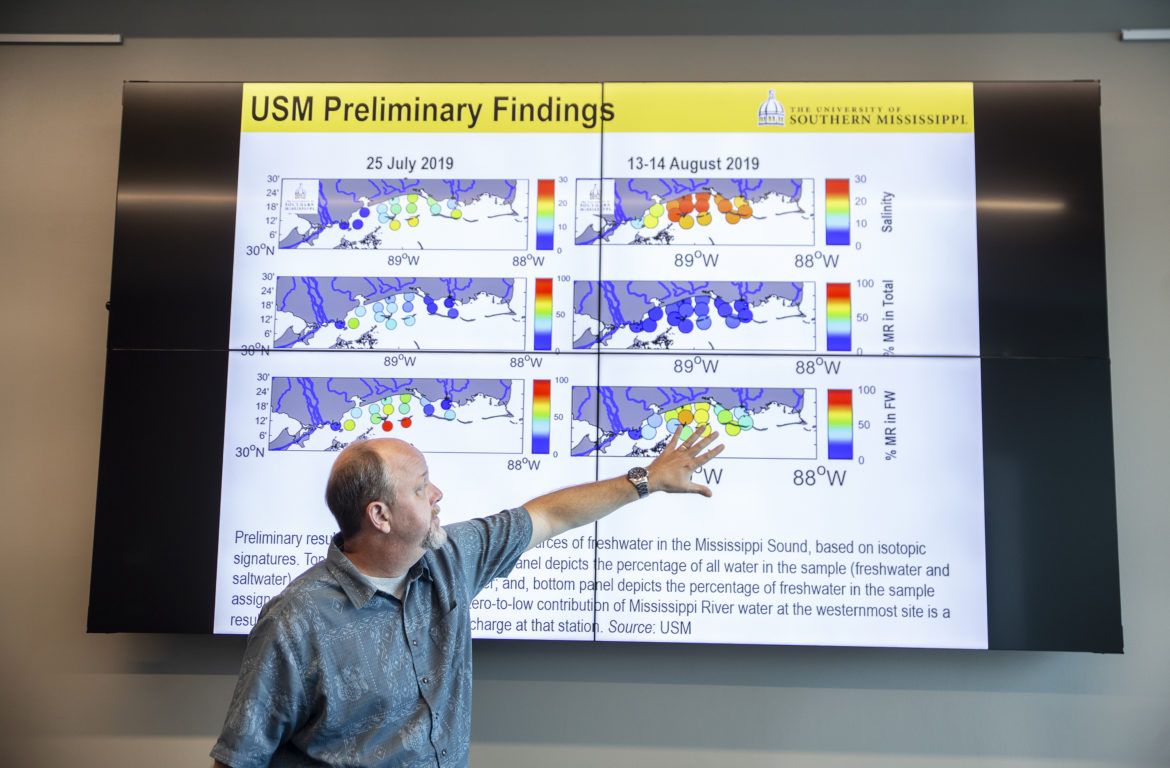

But after historic flooding last year forced the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to twice open the Bonnet Carré Spillway, 95 percent of the state’s oysters died from the sudden change in water quality. Mississippi leadership, which has authorized over $70 million in oyster restoration since 2011, are now reckoning with what a changing climate could mean for their mission.

The bivalves – a type of mollusk with two shells that open and close – are versatile pillars of an ecosystem, filtering nutrients, sheltering fish and impeding erosion. As a food, oysters played a key role in the early coastal Mississippi economy.

Biloxi, the state’s fifth-largest city, developed in its infancy largely in thanks to its tourism and seafood industries. Documented consumption from the area’s oyster reefs date back to the late 17th Century, when French settlers studied the diet of local Native American tribes that included, among shellfish, oysters. By the late 1800s, workers from around the country would arrive by train to work in Biloxi’s seafood hub. By 1903, the city had become the world’s leader in canning oysters.

But the industry on the Coast, once called the “Seafood Capital of the World,” has faced an unprecedented set of obstacles in the last 15 years, leading to Mississippi spending tens of millions of dollars in hopes of reclaiming its 20th century production.

When Hurricane Katrina hit 15 years ago, sediment suffocated the state’s reefs. Just five years later, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill wiped out between 4 and 8 billion oysters in the Gulf of Mexico. Several Bonnet Carré openings since then, including the two last year, have periodically degraded the Mississippi Sound’s water quality to a point where the species can’t survive.

An oyster, which is accustomed to brackish waters, can shut its valves when water conditions are too salty or too fresh, but can only withstand those conditions for so long. Last year, the spillway opened for a combined 123 days, twice as long as any previous opening.

Frank Parker, a fisherman from Ocean Springs, called the situation dismal.

“I don’t see the oyster industry coming back for at least the next five years,” he said. “It’s that bad.”

While oysters themselves take two to three years to reach harvestable sizes, the reefs where they live take years longer to fully recover. To reach a healthy and functional stage, the reefs require generations of oysters to build on top of each other.

With these disasters so clustered together, the reefs have had little chance to rebuild. Between Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the 2016-17 season, Mississippi caught an average of 91,000 sacks, a far cry from Bryant’s 1 million annual-harvest goal.

In terms of weight, Mississippi averaged 1.6 million pounds from 1950 to the year before Katrina, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s landings database. Since then, the state has averaged 699,000 pounds, a 57 percent decrease, and doesn’t include the two seasons – this last one and the one after Katrina – when Mississippi had no harvest at all.

From beach to beach, tourism breathes life into the Coast’s economy. Travelers nationwide come to gamble, drink daiquiris and eat po’boys. In Pass Christian, home to the state’s largest oyster reef complex, Mayor Chipper McDermott bemoaned the impacts of the last 15 years on his city’s economy: “I mean, you ain’t coming down here to climb mountains.”

The city’s also home to one of the region’s largest oyster processors, Crystal Seas, where manager Jennifer Jenkins said the dealer’s year-to-year earnings showed a 50 percent loss in 2019. While the business is getting by with oysters from Texas, she said it’s hard to see a future if the Bonnet Carré keeps opening at its present pace.

“Until there’s a change, I don’t see what can be different,” Jenkins said. Crystal Seas bought over $1 million worth of shells to put on their private oyster reefs, which after the spillway openings were rendered “complete garbage,” she added. “They were ready to be harvested this summer.”

Mississippi has two lawsuits pending against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the spillway, in hopes of finding a new solution to wrangle the ever-flooding Mississippi River.

At the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, the agency tasked with managing the state’s over $2 billion in BP restoration funds, records show over $18 million of that money has gone towards oyster restoration since 2012, with another $30 million budgeted through 2024. The state also has dedicated $30 million toward a project to include oyster spending.

Joe Spraggins, director of the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources, which oversees the state’s Coast fisheries, said Mississippi has spent another $25 million to $30 million since 2011 on reef repair, mostly from other federal disaster funds.

With no control over when the spillway opens, Mississippi is adopting an innovative approach to growing oysters to avoid relying on the traditional reefs that are most susceptible to fresh water.

With the BP funding, the state is investing in three primary avenues: testing different materials for cultch – the surface oysters latch onto – such as crushed concrete, limestone, and recycled shells; developing a “remote setting facility,” where oysters are grown in a University of Southern Mississippi lab, allowed to mature and then planted in the wild; and off-bottom farming, where the creatures grow in movable cages submerged in the water.

“It’s a big puzzle,” said Chris Wells, interim director of the environmental-quality agency, describing each experiment as a piece to building a collectively sustainable oyster population. “It’s certainly disappointing to know that we lost so much of our oyster stock because of the (Bonnet Carré openings), but I’m not deterred from the work we’re doing.”

Some of the BP money went to reefs that were damaged last year – $10 million for a reef in the Western Sound and $3 million for a new reef in Heron Bay. While almost all of the oysters there died, Spraggins said the reefs will still be usable after some repairs.

Still, last year should serve as a warning that the state can’t rely on its old habits, one researcher said.

“Hopefully this will be something the state looks at as a reset,” said Read Hendon, Associate Director of the University of Southern Mississippi’s Gulf Coast Research Laboratory. “We’ve always gone and put oysters and cultch material in the same spot and the same way. I think if we’re going to have a viable industry that all these commercial fishermen rely on, we’re going to have to think differently about how we restore from this event.”

In Ocean Springs, Parker said his ancestors came to Biloxi in the 1850s, and started fishing after returning from the Civil War. He started himself at age 13, when he learned he could make money catching and selling crabs.

Decades later in 2019, he was one of a handful of participants in the state’s new off-bottom oyster farming program. But while some farmers were able to move their cages before the fresh water arrived, Parker wasn’t as lucky.

“We’d been doing it about 11 months,” he said. “I could’ve harvested them but I was holding off, holding off, and I waited too long and the fresh water killed them.”

Parker also sells shrimp and crab, both of which saw over 50 percent mortality rates last year. At this point, he’s tired of the state pouring money into a resource that continues to fall apart. Specifically, he points to millions of dollars invested by the state and private companies over the years in oyster reefs that he believes have been wasted because of the Corps’ management of the spillway.

“We need a seat at the table,” he said.

On a Friday morning last October at Crystal Seas, Jenkins walked through the empty processor, normally a bustling atmosphere filled with shuckers. By around 10 a.m., most of the staff had cleared out.

“You can see a lot of pain in people’s faces because they don’t know what they’re doing,” she said. “It’s their whole entire career and lifestyle. They’ve grown up around it, their family has done it, and they don’t know how to not do it.”

Reminiscing over his childhood on the Coast, Mayor McDermott said it felt like half the town was involved in the fishing industry in one way or another when he was growing up. According to him, Pass Christian used to be home to one of the world’s largest reefs. God himself put those oysters there, he said.

“It’s been like that since Adam and Eve,” McDermott said. He said he likes to grab a six-pack of beer, scoop raw oysters straight out of the shell, and “just eat until I can’t eat no more. But that’s not easy to get right now.”