The assassination of a major Kurdish opposition leader has highlighted sharp political divisions among Kurds here, raising questions about what role this ethnic minority will play in the protests wracking their country. Mashaal Tammo was killed on October 7 when masked men pulled him out of a house in Qamishli, where he was meeting with other activists, and shot him dead.

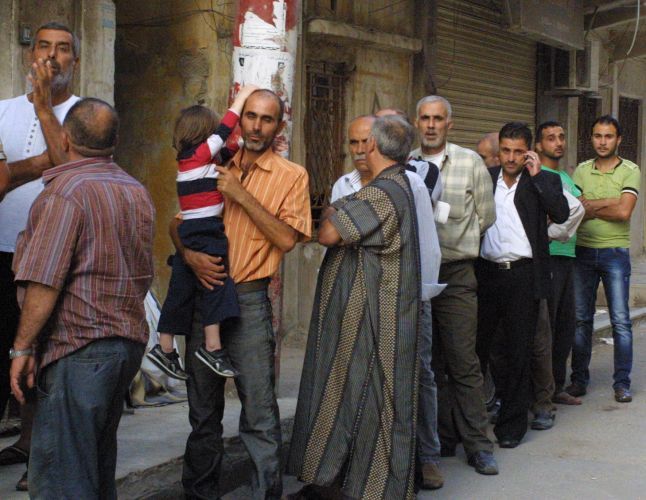

Opposition activists immediately accused Syrian authorities of carrying out the hit, though the government of President Bashar al-Assad denied responsibility. Tens of thousands of Kurds demonstrated during Tammo's funeral in the northeastern city of Qamishli.

Tammo was a leader of the Kurdish Future Movement Party, one of three Kurdish parties calling for the overthrow of Assad. The nine other Kurdish parties have not officially participated in the anti-government demonstrations.

The dispute among Kurdish political parties is part of a wider division among Syrian Kurds. Many worry that that Islamist opposition parties, should they come to power, would be worse for them than the current government.

Mohammad Farho, a Syrian Kurdish commentator and activist living in Erbil, Iraq, told me, "Kurds are afraid of the Arab opposition parties because their agenda is not clear."

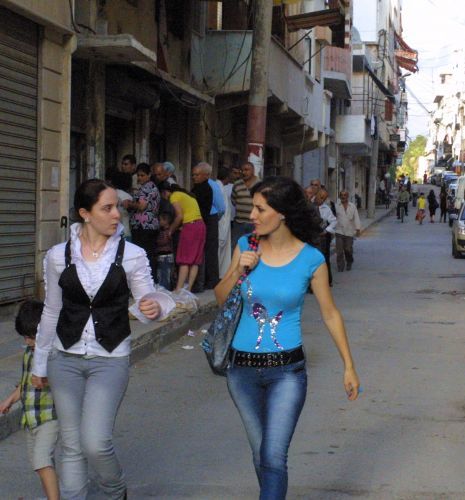

Kurds make up about 8 percent of Syria's 22.5 million people. Though Kurdish language and culture separates them from Arab Syrians, many have assimilated into Syrian society.

Assad's government considers the Kurdish-dominated northeast of the country strategically important because it borders Turkey and Iraq -- and because it contains most of the country's limited oil supplies. The government also fears that Syrian Kurds, like Kurdish groups in neighboring states, might seek independence. All Syrian Kurdish parties currently reject separatism, however, instead demanding greater rights within Syria.

Kurds have long faced government discrimination here. Some 300,000 have been denied full citizenship, fueling anger against the government. Schools are forbidden to teach the Kurdish language and Kurdish businesses have been forced to adopt Arabic names. Under pressure from the current protest movement, Assad recently restored citizenship to many of the affected Kurds and promised further reforms.

When mass demonstrations broke out seven months ago, and the military attacked such Arab cities as Homs, activists say the government shrewdly decided not to attack majority Kurdish areas.

"The regime tried to neutralize Kurds," explained Hassan Saleh, leader of the Kurdish Yekiti Party. "In the Kurdish areas, people are not being repressed like the Arab areas. But activists are being arrested."

Younger Kurds have defied their traditional party leaders, however. Hundreds demonstrate each week, demanding the overthrow of President Assad.

After seven months of frustrating protest and government violence, some Kurds now call for western military intervention to topple the government. Others plan to smuggle arms from nearby Iraqi Kurdistan to engage in armed self-defense.

Can Med, a leader of the Democratic Union Party, told me that he calls for limited foreign military intervention to protect civilians and topple Assad. He says his party is also preparing for armed struggle.

The Democratic Union Party is affiliated with the PKK (Kurdish Workers Party) in Turkey, which the U.S. labels as a terrorist organization. The PKK describes itself as a legitimate national liberation group.

"If you want to get arms in the Middle East, it's easy," said Med. "We can do that."

But armed resistance and foreign intervention are still controversial topics within Syrian Kurdish communities. "I don't back such calls," Hozan Ibrahim told me. He is a spokesman for Local Coordination Committees of Syria and now lives in Germany. "It's the call of people under fire, so they need someone to rescue them. Unfortunately some feel that the regime can't be removed without armed action either from inside or outside."

Activists inside Syria report that Kurdish participation in demonstrations increased recently as fierce government repression spread in other parts of the country -- and particularly after Tammo's assassination.

"As the number of deaths increased, the number of demonstrations grew," said Ciwan Yusuf, a spokesman for the Sawa Youth Coalition.

Under current conditions, Yusuf does not favor foreign military intervention, he said, worrying that it would result in many deaths and that foreign powers could ultimately impose undemocratic leaders on Syria.

As an alternative, he urged Western powers to help find neutral countries for opposition leaders to meet and to increase economic sanctions against Syrian government officials.

Kurdish activists, like those throughout Syria, face difficult times in the months ahead. Government repression continues unabated. Some in the opposition movement are increasing violent attacks on government targets in a desperate attempt at regime change. For the moment, neither side seems able to win a decisive victory and Syria's turmoil seems likely to continue for some time.