Objective:

Students will be able to evaluate how an author emphasizes details about Indian Residential Schools using different multimedia by analyzing articles from the project “Signs of your Identity” and creating a photo-blend portrait based on an interview

Warm-up:

Discuss with a partner and/or write down your responses to the following questions:

- What are words you use to define your identity?

- What is the role of school in forming your identity?

- What makes a school a positive place to be and what makes a school a negative place to be?

Introducing the Lesson:

Read the following introduction to journalist-grantee Daniella Zalcman's project “Signs of Your Identity” and consider the following:

- How much do you know about residential schools?

- Why might this be a subject that people don’t know much about?

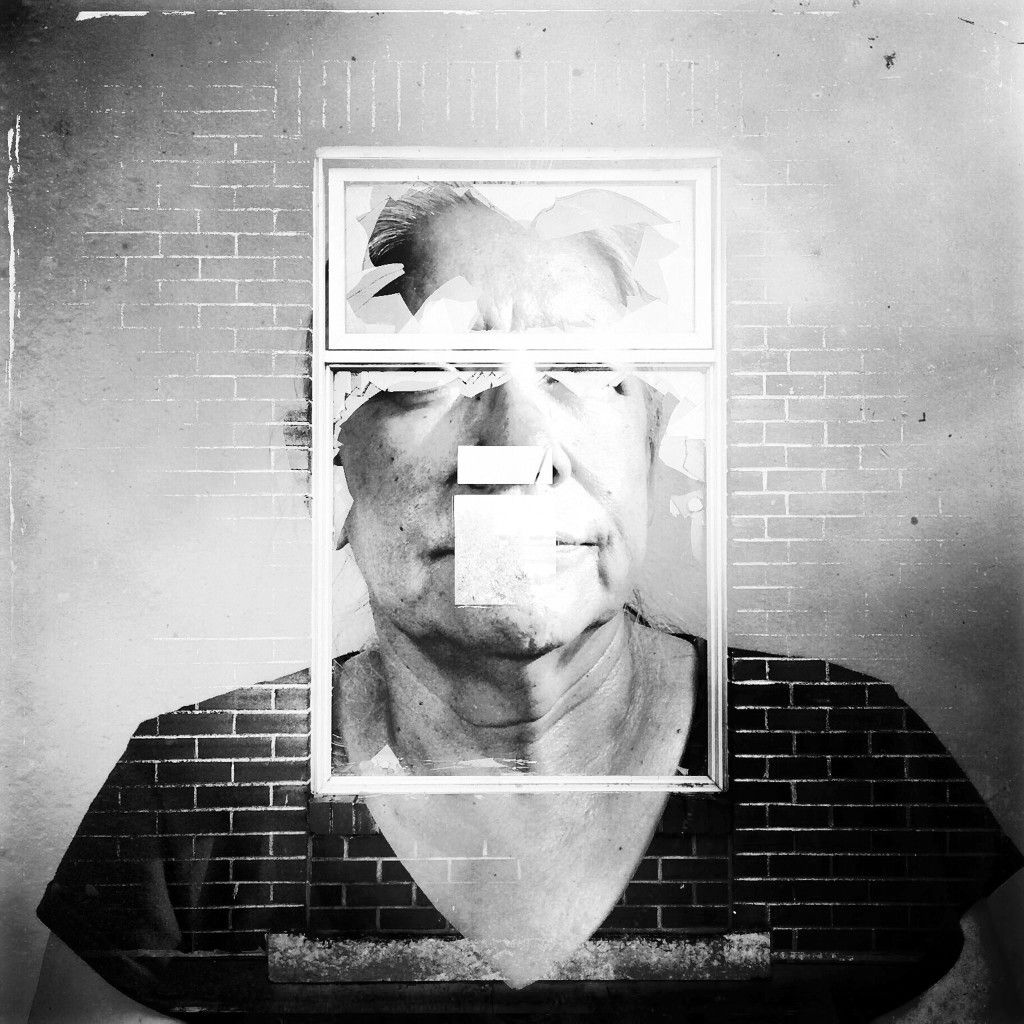

Daniella Zalcman’s project, “Signs of Your Identity,” explores the legacy of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools, which began operation in the late 1800s. Attendance at the schools was mandatory, and agents would regularly visit reserves to take children as young as two or three from their communities. Many of them wouldn’t see their families again for the next decade. These students were punished for speaking their native languages or observing indigenous traditions. In interviews with the people she met, Zalcman heard stories of routine sexual and physical assault.

The last school closed in 1996. The Canadian government made its first formal apology in 2008. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission that concluded in 2015 officially labeled the system cultural genocide.

Today’s lesson analyzes how an author emphasizes different details when communicating a subject using multimedia. The photos featured in this article use the PhotoBlend app to blend two images into one image.

Introducing Resource 1: "Pictured With Their Past, Survivors of Canada's 'Cultural Genocide' Speak Out"

Use the questions attached to explore the National Geographic article. As you go through each question, consider the following:

- What details are emphased by each piece of writing/media?

- What is the impact of looking at photos and text together?

- How does the school environment impact the identity of a student?

After reading:

As a class, discuss what additional information is communicated in the National Geographic text.

Brainstorm words to describe the tone of the text. How is it alike/different from the tone of the photo slideshow?

With a partner, create a plan for photo blend portraits of Janet and Deb. Consider the following:

- How would you design your photo of each person?

- What would you want to photograph to blend with the images of Janet and Deb?

- What text would you use in the captions?

Be prepared to share your plans with the class.

Extension:

Read the attached article “Healing After a Century of Discrimination in Canada” and use the photos included in the article to plan three photo-blend portraits. Consider the following:

- Which subjects would you want to photograph?

- What text would you use in each caption?

- What images would you use for the photo blend?

In the project “Signs of Your Identity,” Zalcman writes, “How do you photograph the past? How do you show what remains in the wake of so much trauma and abuse?”

Identify someone in your life (a classmate, a teacher, a parent, someone that works at your school) to interview about their identity. In your interview, find out how an event (positive or negative) impacted the person’s identify. Photograph the person and the blend that image with another photograph to communicate what you learned in your interview. Use your interview to create a caption for the photo.

Once you finish, tweet your photos to Daniella Zalcman @theempathygap

In this lesson plan, students will examine the impact of Indian Residential Schools run by the Canadian government throughout the 20th century by reviewing interviews and photography from Pulitzer Center journalist-grantee Daniella Zalcman. Through project-based learning, discussion and reading, students will evaluate how an author emphasizes details using different multimedia and explore the impact of a school environment on personal identify.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.7

Analyze various accounts of a subject told in different mediums (e.g., a person’s life story in both print and multimedia), determining which details are emphasized in each account.

Lesson Facilitation Notes:

1. The lesson plan is written for students to be able to explore the resources independently and reflection exercises independently.

2. Students may need to have an extra sheet of paper, or a blank online document open, to answer the warm up, comprehension and extension questions.

3. The lesson lists several extension exercises. Students could choose one or work through all of the listed exercises.

4. The warm up and post-reading reflections in this lesson could also lead to rich conversations. You may want to work through the lesson along with the students and denote moments for interactive activities.

5. With questions about this lesson, contact [email protected]

![An Asian conical hat—purchased when Ms. Bellaire believed she might be of Asian descent, hangs at her home. For Ms. Bellaire, it is a reminder of the decades long journey to discover her roots. "My mom went to Indian residential school, so she [left the reserve and] raised us in town so we could never be found," she said. Image by Daniella Zalcman. Canada, 2014.](https://legacy.pulitzercenter.org/sites/default/files/styles/node_images_768x510/public/03-02-15/bn-gw665_pbzalc_j_20150209215151_0.jpg?itok=f2a5j2k5)