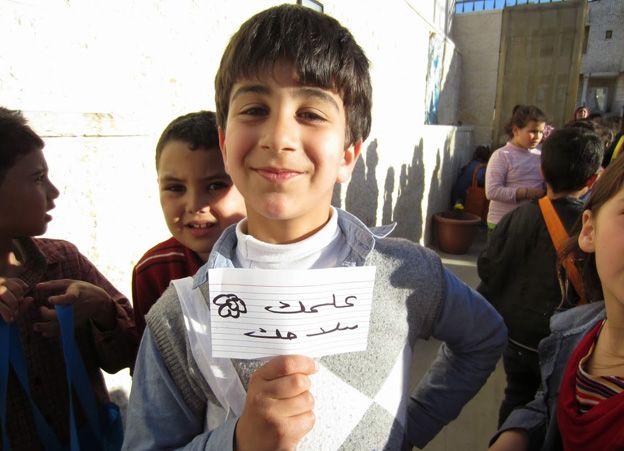

This is a photo of a drawing by a Syrian refugee child in Jordan. Image by Lauren Gelfond Feldinger. Jordan, 2014.

These days, it's hard to miss news of Syria's refugee crisis; this is the largest number of people on the move since World War II. Lauren Gelfond Feldinger reported from Jordan on a volunteer organization working with several hundred Syrian refugee children there.

The story's teaser: "To combat the values of groups like IS and a regime that doesn't represent them, a group of young Syrians tries to pass its values of non-violence, pluralism and hope to Syrian children. They see them not as a lost generation, but the country's next generation, reports Lauren Gelfond Feldinger."

Excerpt from “Syria’s Next Generation” by Lauren Gelfond Feldinger

Published March 12, 2015

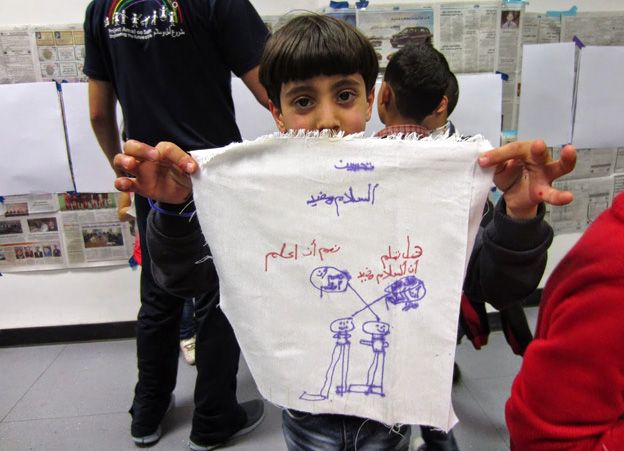

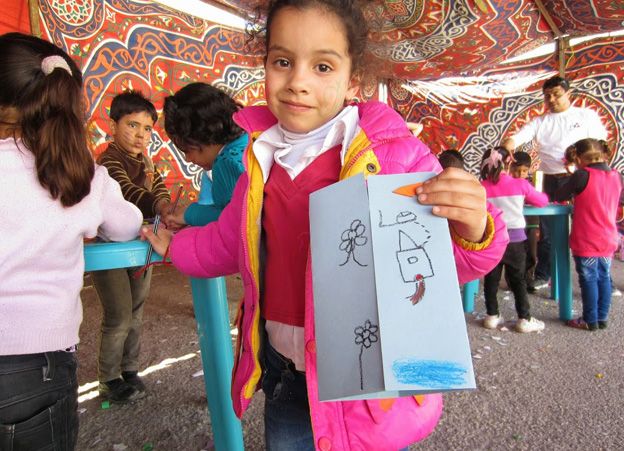

Redirecting the energy, songs, conversations, drawings, behaviour and mood of the children so that they will feel they have something to look forward to requires easy adjustments, [“Amal ou Salam" organization founder Nousha Kabawat] explained. "We want to focus on positive things." For example, a question about the future: "After the conflict is over we have to rebuild Syria - what do we need?"

Five daily workshops she designed relate to child-friendly conflict resolution theories:

-arts and crafts use urban-planning tools to redesign destroyed neighbourhoods after the war, working with neighbours of all religions and backgrounds to meet everyone's needs

-photography teaches multiple perspectives

-music encompasses music-therapy techniques to soothe, and basic music theory to teach that diverse people who never studied instruments can work together to create one beat

-sports and team-building show that working together creates more success, strength and trust

She summed up with a wink: "Cemeteries no, rainbows yes."

Kabawat honed her theories while earning a Master's degree in conflict resolution in the US, focusing on peacebuilding in post-war societies. Afterwards, in 2013, she found children in a Syrian camp bored and mimicking the language of anger, violence and sectarianism around them. Relief efforts helped with physical needs, but she started imagining a volunteer-led programme to feed the children's self-esteem and character. Consulting conflict resolution experts, primarily at George Mason University in Virginia where she had studied, she planned a programme of travelling workshops to feel like summer camps. Without a background in business, fundraising or management, she used a web campaign and social media to fundraise and recruit volunteers.

After quickly raising $7,500 for a pilot project, she went in summer 2013 to Turkey with seven volunteers to work with 400 children and then to Lebanon to work with 100. As she had no overheads or salaries to pay, and overseas volunteers paid for their own travel and hotels, the money went on art supplies, rented spaces, food and buses.

When I meet up with the group in Jordan in 2014, she has raised $25,000 and recruited 33 volunteers to work with 1,000 refugee children. She has also started sending supplies to Syrian schools. Her dream, she says, is to "eventually reach hundreds of thousands of children".

Kabawat, young, female and Arab, represents a new generation of conflict resolution leaders in a field traditionally led by older men. With her frenetic energy, charisma and banter, she is easy to imagine not long ago as a tough, popular high school student. But talking one-on-one, she is sombre.

"As Syrians, we've aged so much in the past year it feels like four," she says, leaning her head and rubbing her eyes, as if to scrub away the tragedies she reads about daily from contacts back home.

"Children," she says, "are the only hope now left for Syria."

Meeting the children

The bus pulls up to the gate of a spotless state-run orphanage that Kabawat has rented in the hills of Irbid. Jordan's second largest city hosts about 140,000 refugees, though all we see in the near distance are dry grassy hills, except for a villa, surrounded by Bedouin shacks. Black-and-white sheep graze around them. The orphanage facade, like all the schools and many buildings in Jordan down to some falafel shops, boasts mammoth posters of King Abdullah II and the late King Hussein.

Inside the gated courtyard surrounded by sandstone walls, it is quiet until the buses rented by Kabawat pull up and 200 six-to-13-year-olds pour in.

Syrian activists estimate that at least 200,000 people have been killed in Syria since 2011 and nearly half the pre-war population of 23 million has been displaced internally or to neighbouring states. Despite the news focus on refugee camps, 84% of the 631,000 Syrian refugees in Jordan live in host communities, according to the UN. About half are children, many of whom are not schooled.

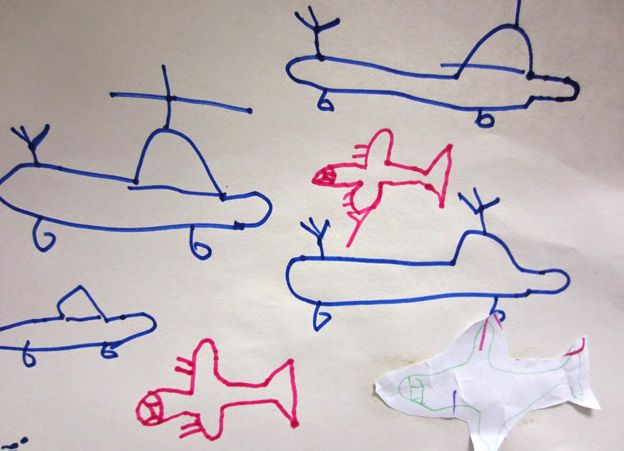

Three years before we arrive, they were just a few kilometres away on the other side of the border. They would have heard about other children close to their age in Dera'a, who had scrawled graffiti calling for the fall of the regime. The government jailed and tortured the children and mocked the desperation of their parents. Non-violent protesters chanting "hurriyeh" (freedom) and "karama" (dignity) were met with tear gas, arrests and torture. Syrian forces, IS, the Nusra Front and multiple militias have long since rolled over the non-violent revolution.

To meet the child survivors, we have woken at 6am in Amman to arrive by 8am. A sea of smiles and clean, colourful outfits stare back at us. The kids have fled ravaged districts that look like scenes from Europe at the end of World War Two, yet their traumas are not immediately obvious. A volunteer whispers that several have hearing aids, a result of explosion-induced hearing loss.

Many of the boys have black eyes. James Gordon, a US-based psychiatrist, abruptly comes to mind. He has worked in war zones from Bosnia and Kosovo to Gaza and Israel and in such disaster zones as Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina and Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Everywhere, he told me when I interviewed him in Jerusalem two years ago, he found the same results: survivors of war and disaster often beat their children.

The powerlessness they feel, coupled with traumatic memories and harrowing losses, often lead them to impulsive, violent behaviour they later regret.

Children, he said, are at multiple risk because they often have their own post-traumatic stress, which can cause them to express themselves more violently. They model themselves on the way the adults around them deal with anger, and they often become victims of adults and children who lose their tempers. But there was hope, Gordon emphasised: the tendency towards violence and hopelessness that follow traumatic events can be quickly assuaged if those affected learn optimism, self-expression, and ways to calm their nervous systems. I look around and wonder.

Using this Lesson:

- Read the above excerpt of "Syria's Next Generation" by Lauren Gelfond Feldinger and examine the photo above.

- Discuss the questions provided in this lesson.

- Have students research organizations providing aid to Syrian refugees, like "Project Amal ou Salam," the one in the story. Who is doing what? Where are these organizations based? What are the motivations behind them? How are they funded? How can you get involved?