Eight years ago, I visited Afghanistan as a guest of the British army. For two weeks, I drew soldiers in the British camps in Helmand and Kabul. However, I was aware that, outside the foreign fortifications, ordinary life continued for most of the Afghan villagers. Towards the end of last year, I had a chance to go back and see this for myself.

While drawing the Chahar Suq bazaar, in the ancient western city of Herat, a wide variety of locals, young and old, gathered around to watch. A policeman aggressively cleared them away, his AK47 hung high around his neck. It turned out that watching a foreigner draw was too intriguing for the onlookers, despite the threat of a clip round the ear. After the policeman’s third attempt to clear the small crowd, a smile broke out on his face. He hurried back to his post, found an officer who spoke fluent English and, as so often happens in Afghanistan, returned with welcoming cups of tea.

A week earlier, I had been in the Worsaj valley in north-east Takhar province, drawing girls sitting their end-of-year exams. It reminded me of the gym hall where I had sat my own exams; as in England, the classrooms were too small for all the children. Here, however, they take exams outside, surrounded by the snow-capped foothills of the Hindu Kush. It was wonderful to see.

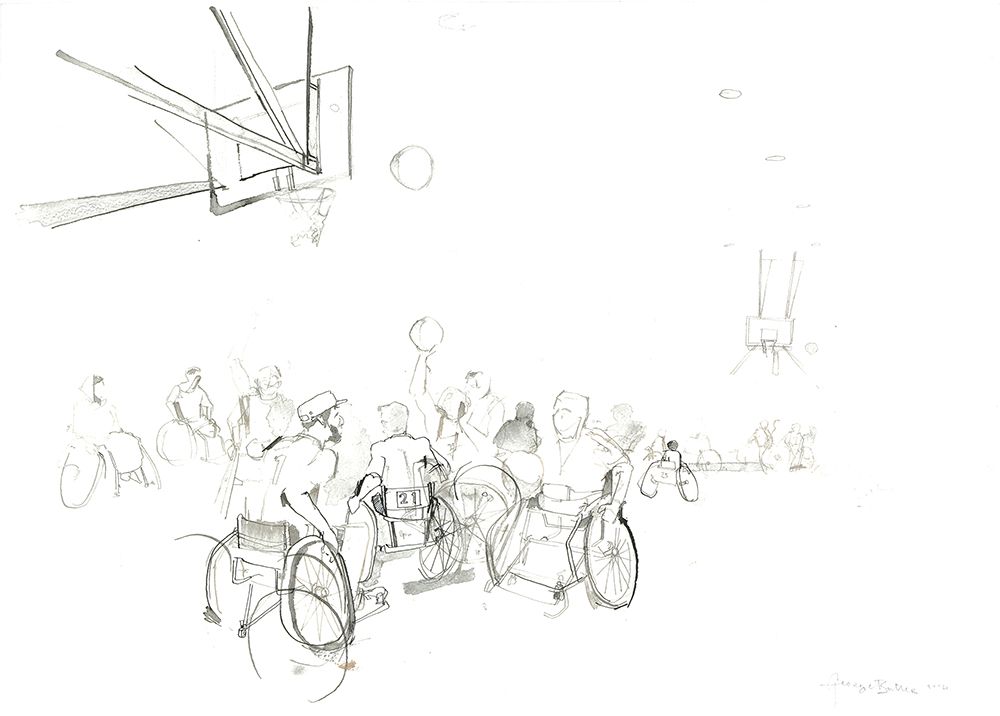

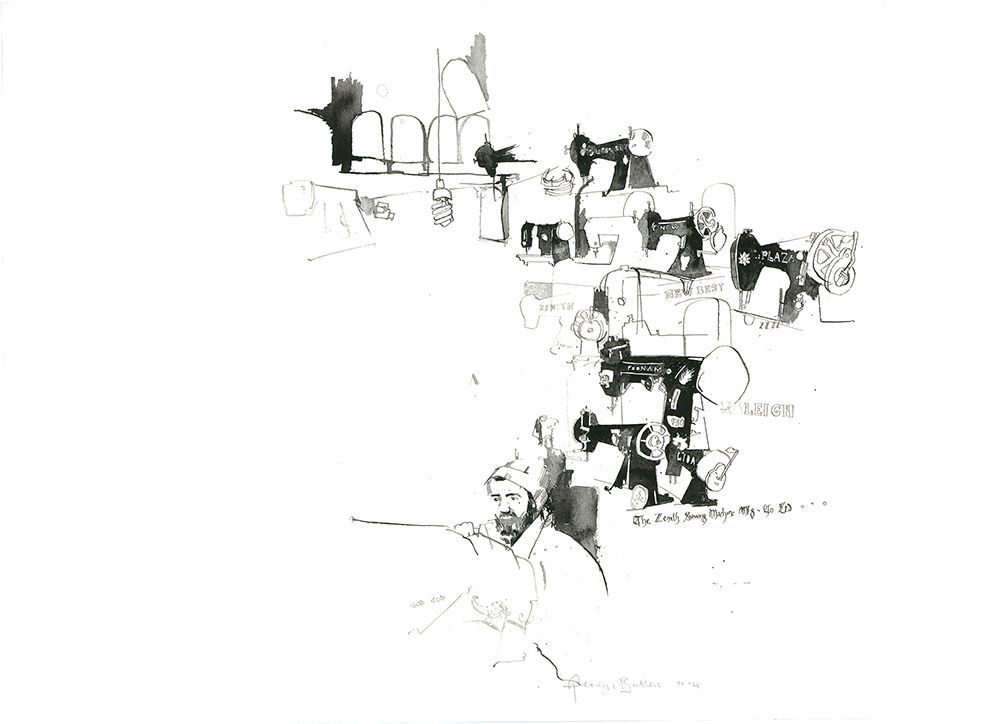

Over the next few weeks, I drew Faizabad market, the police station in Kabul’s District 10, a Red Cross (ICRC) prosthetic limb clinic and the scenes outside Herat’s blue mosque. I drew exhaust-pipe fitters and stovemakers, pigeon sellers and Hajji Mirwais, a sewing-machine vendor. Of course, this is a country where the British have had a mixed reception over the past 13 years, but not once was an unfriendly word directed my way.

That’s not to say I wasn’t aware of the situation that Afghanistan finds itself in today. Almost each day I spent in Kabul, there was an explosion or an attack from an armed group. But I soon realised that, despite the uncertainty and insecurity, the majority of Afghan life continues to be as close to normal as possible.

It was this Afghanistan that I found overwhelmingly inspirational to document. What saddened me was that so many of the articles and reports I read before I arrived – although consistently accurate in detail and honest in their approach – made me expect the worst. This was far from the case in the small parts of Afghanistan I saw, especially in the north and west, away from Helmand and other parts of the south and east, where most of the reports seen on our televisions in UK have come from.