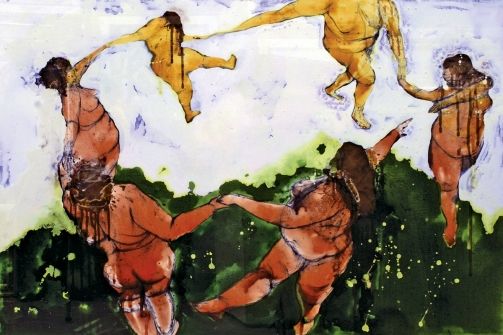

Sublimation is a psychological process in which socially unacceptable impulses are transformed into something less destructive, explains Weaam El-Masry, a fiery Egyptian artist, as she unloads a truckload of her watercolor nudes for sale in a central Cairo art gallery.

“Maybe you have something you want to say—maybe it’s sexual—but society suppresses it,” she says. “When it comes out in your art, that’s sublimation.”

Since the Arab Spring broke out in Egypt a year ago, the country’s art world has started to shake off decades of repression. Sexuality is more out in the open, as are deep-seated social problems such as poverty and corruption—subjects long off limits under former president Hosni Mubarak. Many artists, it seems, no longer feel obligated to cloak their politics in thick layers of allegory.

At Townhouse, a funky art gallery nestled in the heart of central Cairo, iconoclasm is now the rule rather than the exception. In December, the gallery opened D1sc0nN3ct, a dizzying collection of digital-media pieces by a handful of Egyptian artists. Featuring videogames that can’t be won and Web pages with faulty encryptions, the exhibition presents corruption—a debilitating ulcer in a society where you can’t get a driver’s license without paying a bribe—in a daringly critical light.

On the same night but in an adjacent space, the gallery headlined another bold exhibition titled The Politics of Representation. Composed entirely of campaign paraphernalia from the country’s ongoing parliamentary contest—the first since Mubarak’s ouster a year ago—the exhibit takes on the explosion of political activity that has rocked Egypt in recent months and reduces it to a maze of symbols, slogans, and glossy poster stock. According to William Wells, who founded Townhouse in 1998, the exhibition was conceived as an “interactive, real-time visual representation of the electoral process.”

Still, for all the freedom of recent months, El-Masry was reluctant to advertise the most shocking of her 11 nudes that she recently exhibited at Cairo’s El Gezira Art Center. The piece, a 120-by-80-centimeter canvas in pen and dark red watercolor, depicts two naked women superimposed on one another in a distinctly sexual embrace. “I didn’t show that one on the event poster,” she says with a laugh. “I didn’t want the Ikhwan [Muslim Brotherhood] to come and break everything.”

One year on, Egypt’s revolution has opened up space for more criticism of the cultural status quo, but it has also opened the door to other, deeply conservative forces that see much of the recent art as an affront to religion. The Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis, whose ultraconservative brand of Islam was imported from the Persian Gulf, have emerged as major power brokers in postrevolutionary Egypt. Elections for the lower house of Parliament, staggered over the last few months, saw the Brotherhood and the Salafis together win more than 70 percent of the vote.

For artists operating at the margins of social acceptability, the surging popularity of Islamists signals troubling times ahead. El-Masry, whose nudes are risqué by almost any standards, says she is worried about the prospect of an Islamist-dominated government. “They don’t think. They don’t use logic,” she says. “They think art is forbidden.”

The Salafis have done little to dispel this perception. Their leader, Sheik Abdel Moneim el-Shahat (who lost his individual bid for Parliament), recently accused the late Naguib Mahfouz, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988, of “inciting promiscuity, prostitution, and atheism” in his works. Shortly thereafter The New York Times quoted him as saying that citizenship, freedom, and equality should all be “restricted by Islamic Sharia.”

The Muslim Brotherhood has been more tactful, demurring when it comes to how its vaguely stated policy platform would play out in practice. But if its record in Parliament is any indication, the Brotherhood will be no friend of the Egyptian avant-garde.

From 2000 to 2005, the Brotherhood’s 17 members of Parliament, all of whom ran as “independents” because of a Mubarak-era ban on religion in politics, successfully lobbied to ban three books for “explicitly indecent material amounting to pornography.” Meanwhile, Brotherhood parliamentarians devoted 80 percent of their questions to cultural or media issues.

This emphasis on censorship carried over into the 2005–10 parliamentary session, when Brotherhood members introduced legislation to ban art with obvious sexual references as well as concerts that feature female singers.

How far an Islamist bloc in Parliament will be able to push its socially conservative agenda this time around, most experts agree, depends on one huge wild card: the military, which seized control after Mubarak’s departure last February and which has traditionally been a force for secularism. According to Harvard law professor Noah Feldman, who has written two books on Islam and democracy, Islamists and the military have been “locked in a very complicated, subtle, arms-length negotiation dance” since the fall of Mubarak.

For now, it looks as if the military is the leading partner in that dance. The generals, led by Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi, have made it clear that the newly elected Parliament will remain subordinate to the military-appointed cabinet until a new constitution is drafted and a president is elected. And even after Egypt’s military leaders concede some of the day-to-day responsibilities of governance to the Parliament—assuming they do—the Army is likely to wield significant power from behind the scenes. Still, as Feldman cautions, “Islamists are going to have some degree of social-conservatism-style veto. I think that’s almost inevitable.”